“There are no doors anymore, no steps leading up to doors, no portals. The doors are a cut-out piece, you donʼt enter a house […], there is no threshold […]. Doors have lost their meaning.

Dr. Karl König, 1965

People are a mass society, not anymore an order. We have a mass of mirrors, a mass of windows, but no door anymore.”

Louis Kahn would have agreed: “there are no doors anymore,” a statement made by the Austrian author and pediatrician Karl König (1902-1966) when lecturing on the meaning of modern architecture in 1965, shortly after Kahn (1901-1974) ‒ an Estonia-bord American architect ‒ finished up his vision to reshape an entire city center in North America. Someone who only in the latter part of his lifetime, after practicing and teaching architecture for several decades, saw the fruits of his labor; an outsider to the trends of the International Style-fanatics who dreamt of columns as thin as stamen, skins like water; Kahn was by no means at home in this “mass of mirrors.” Luckily for him, the thin wall-planed pictorial phase of the twenties and thirties came to a close and in the two following decades the principles of modern architecture were approaching those which Kahn learned and developed during his time at the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a student. Here, under the mentorship of Paul Cret (1876-1945), Kahn was part of an academic curriculum that centered upon the French École des Beaux-Arts, an architecture style taught in Paris from the 1830s onwards, which drew from various traditional styles: Neoclassicism, Renaissance, and Baroque, primarily applied in civic typologies. Even though Beaux-Arts was understood to be bankrupt of ideas by the early twentieth century, the solidity of its academic theory and the emphasis on mass and weight, found its way back into the architectural discourse.2 The return to this academic tradition also brought forth a reappearance of the architectural paradigms of the French Enlightenment; an employment of Platonic solids in a way that drew from the imposing imagery produced by both Boullée and Ledoux two centuries before.3 Here, Kahn felt at home.

The revival of this monumental approach to building was in fact a consequence of a political situation the United States found itself in, especially after the Second World War. As argued by the architecture critic Kenneth Frampton, the social provisions and reform programs of Rooseveltʼs New Deal ‒ which intended to pull the country out of the Great Depression, were after the war substituted by an “incipient impulse towards monumentality”.4 Supposedly emerging out of a demand for the countryʼs status as a world power, the United States were about to enter a phase of “unprecedented monument-building,” a direction which was already formulated in a manifesto that put the theme into discourse: Giedion, Sert and Legerʼs Nine Points on Monumentality of 1943.5 Both Kahn and the chameleon-architect Philip Johnson (1906-2005) ‒ who was about to exit his Miesian phase ‒ would become leading proponents of the same tendency Le Corbusier developed in Europe at the time: monumental buildings that through their plastic presence symbolizes characters that could “give identity to the society for which they are built”.6 It is within this development, that a year after the proposed manifesto, Kahn published an essay entitled Monumentality (1944) ‒ a groundwork for his later architectural achievements, such as the Salk Institute for Biological Studies (1965) (fig. 2), and the Kimbell Art Museum (1972) (fig. 3). Yet, in the shadows of those major works sit various attempts that exceed the scale of architecture; imposing alterations of urban sites produced shortly after Kahn developed his ideas on the theme, a monumental approach most vividly expressed in his urban visions for the city he grew up in: Philadelphia.

This paper examines Kahnʼs Plans for Midtown Philadelphia, proposals of urban renewal developed by the American architect between 1951 and 1963, which never saw the light of day. The material which is included in this study are the Traffic Study of Philadelphia (1951-54); Penn Center and the City Tower Project (1951-58); Market Street East Studies (1960-1963); and his Viaduct Architecture (1959-62). All four developments are complementary or logical successions and must be brought in relationship to grasp the full scope of Kahnʼs urban intentions, produced for the city he, as a child, immigrated to. While those attempts of urban renewal vary in completeness, some were detailed and – as Kahn would have said ‒ ripe for execution, while others are rough sketches taken from Kahnʼs notebooks; their underlying intention to solve a rather problematic urban situation of postwar metropolitan development, will be placed both in relation to his ideas on monumentality, as posed in his manifest of 1944; and the period in which the plans were ought to be realized. Published in an article written for Yaleʼs School of Architectureʼs Perspecta of 1953 – where Kahn taught, those urban imaginaries sticked to the drawing board, a fate which they from the first moment entailed, if we listen to his critics at the time: his plans were labeled too idealistic and naïve, distant to the reality of the tasks at hand, and simply operative in a poetic idiom.7 This paper will in turn answer the following two research questions: how did Louis Kahn implement his ideas on monumentality into the urban scheme of Midtown Philadelphia, as developed between 1951 and 1963; and were his proposals feasible and appropriate for the metropolitan milieu of postwar Philadelphia, or should they be treated as romantic chimera of an architect who had no formal training in the field of urban design whatsoever?

Kahn and Philadelphia

Born on the unpopulated island of Saaremaa, west of Estoniaʼs coastline, Kahnʼs world was small and confined; his horizons framed by the shores he could see from the kitchen window; proportions a child would have felt secure in. Yet, at the age of five, Kahn was thrown out of this womb and faced by fleeting images of incomprehensible size: volumes without ends, each a horizon in itself. When the Kahn family immigrated to the United States in 1906, their arrival at the New Jersey Bight would probably have set such images; they had an impact: “a city is a place where a small boy, as he walks through it, may see something that will tell him what he wants to do his whole life,” Kahn said in his later years.8 To him, this was the case; Philadelphia was that source, after having arrived through its harbors. It can therefore be said that the many attempts of drawing, reimagining, and developing this very city throughout multiple decades of his practicing career – even though he was at most times not commissioned to do so – stem from a personal relationship formed at a young age. To understand those attempts of urban renewal, what he envisioned, and why he believed they were necessary, we must first paint the picture of the city of Philadelphia, starting at the first, formal city plan of 1682 by William Penn ‒ the founder of the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonial era. It is from its chronological development that we may grasp the meaning of Kahnʼs later attempts.

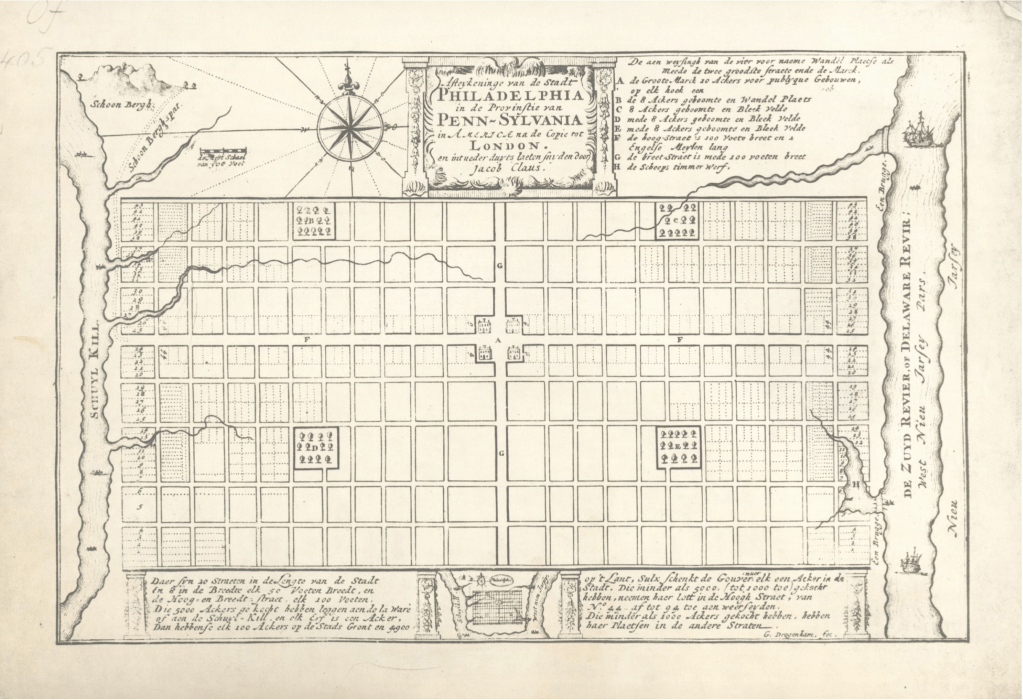

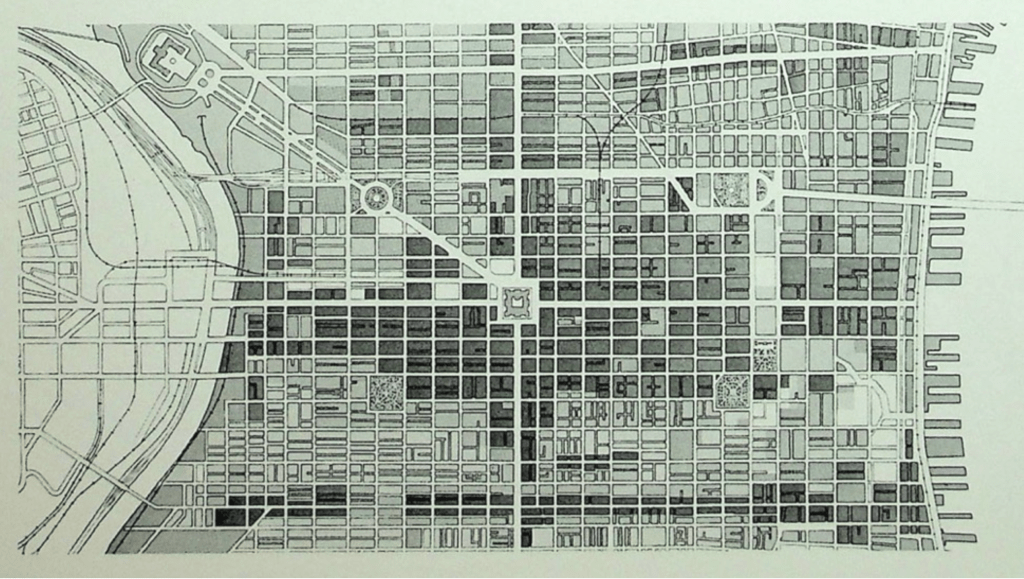

When at the latter part of the seventeenth century the city of Philadelphia (Pennsylvaniaʼs largest city) was founded on a relatively small plot of land in between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers ‒ the former opening up to the Atlantic Ocean, splitting the states of Delaware and New Jersey, the English Quaker laid out a grid-system that provided the centrality and clarity of form the city has retained throughout centuries; a layout which stretched the full width of land between the rivers, divided into four quadrants by two main thoroughfares, High Street (now Market Street) and Broad Street, with Central Square at its intersection (fig. 4). As simple as the idea was, in the quadrants sit secondary squares, in turn the focal centers of four phases of Philadelphia life: Franklin Square, the center of commercial and industrial renewal (N-E); Washington Square (S-E) for historic tradition; Rittenhouse Square, housing cultural and scientific developments (S-W); and Logan Square for cultural institutions (N-W).9 Almost all future developments, such as railroad tracks and subway tubes, have followed this layout (the 30th Street Station is also placed on the east-west axis), except for a diagonal wedge of greenery extending from the City Hall on Central Square to the Art Museum in the north-west flanking the Schuylkill river, known as the Fairmount Parkway plan of 1917 ‒ a cultural boulevard planned to bring green into the city and in line with the allotted, cultural purpose given to this quadrant by Penn centuries before. As a result of this strip of cultural institutions, the city center gravitated slightly toward the north-west, with two extra east-west throughfares as a result, as can be seen on the plan of 1962 (fig. 5). Although the four quadrant squares are still indicative of the edges of the Pennʼs original design, with the rivers implying its east and west boundaries, the grid has extended both far into the north and south of the city, making it largely unrecognizable. For a long period of time the development of Midtown Philadelphia halted, which was a result of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the so-called Chinese Wall: a collection of railroad tracks in east-west direction which closed the city center off from its northern suburbs.10 In combination with the edging rivers, Midtown Philadelphia appeared as an island, secluded from the rest of the city. After several decades of inactive planning, exacerbated deindustrialization, and incidences of urban civil uprising around the country, Philadelphia appeared in a “critical state of decay”.11 In response, it was during the postwar period that the so-called Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC) actively anticipated on its urban renewal. Those developments were led by the executive director and urban planner Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), a figure who from 1949 to 1970 had an effective imprint on the cityʼs course of development. Drawing inspiration from the renowned Jane Jacobs, his ideas to include local communities in planning processes, making the city fit for pedestrians, and his opposition of suburban sprawl, were – although idealistically representing those values – in reality obscured.12 As a matter of fact, during the 1950s Bacon acted primarily as a counterweight to another figure whose visions were much more ideologically fueled: Louis Kahn. Named Master Planning Consultant from 1946 to 1954, the latterʼs ideas seemed to surpass the reality of the tasks at hand: romanticized urban visions to which Bacon represented as opposition, embracing a more practical and economically viable attitude. While it seems rather fitting that Kahn labeled Bacon as “a planner who thinks he is a politician,” the opposition between those two figures actually sets the context of development in mid-twentieth century metropolitan Philadelphia, primarily shining light on a particular topic which initially provoked the debate: how to deal with modern locomotion.13 While Bacon believed that the car incubated the cityʼs economy, and “must be treated as an honored guest,” Kahn felt that in order to preserve the quality of life in an urban center, cars and roadways had to be halted on its periphery.14 The latterʼs urban visions all incline a response to what he believed was a threat posed by the mechanism and infrastructural demands of the automobile: “The demands of the car will eat away all traces of what I call loyalties ‒ the landmarks. The places which identify the city, as you enter it. If theyʼre gone, your feeling for the city is lost”.15

Form and Defense

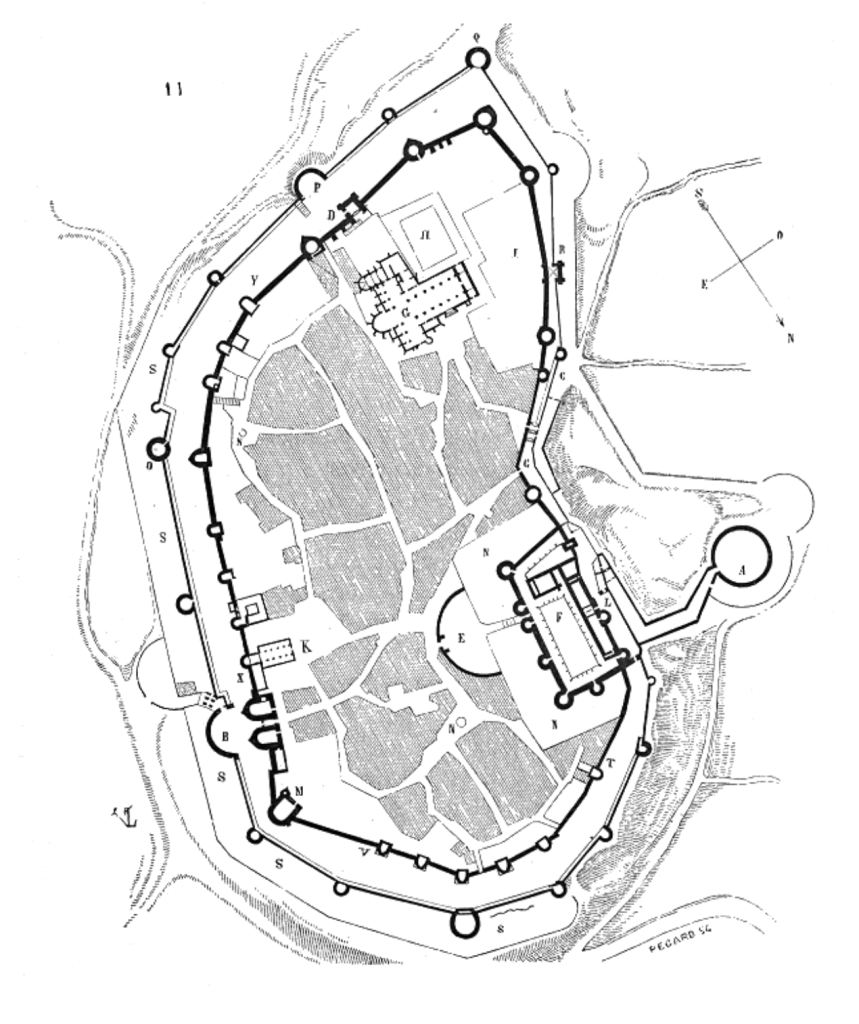

Kahn was an agent of form, and in the city of Philadelphia he saw it disappear: while “the [quadrant] squares still have their lasting quality of holding the center, […] I feel that the center still has no real unifying character”.16 In response, Kahn imagined Midtown as a walled, medieval defense mechanism ready for battle, with bastions pondering thick shadows in front of its walls. This wall had two purposes: it would give form, a sense of containment to Midtown, and defend itself from intrusion of a particular kind: an army, not of men, but of cars. When describing his plan, Kahn actually made reference to the walled city of Carcassonne in Southern France (fig. 6, 7), which he learnt through drawings by Viollet- le-Duc ‒ who restored the citadel.17 Like this medieval fortress, which was designed from an order of defense, Kahn believed the modern city would “renew itself from its order concept of movement which is a defense against its destruction by the automobile”.18 How did Kahn envision this? Namely: in the form of a chain of encroaching cylindrical parking towers, encircling an interior space where the cityʼs monuments and civic institutions would be housed (fig. 8). While in his earlier Rational City studies of

1939-48 Kahn projected Corbusierʼs Ville Radieuse onto the city center of Philadelphia, and committed to a decentralization of civic institutions, in the figured drawing published in 1957, Kahn turned fully toward the belief that the city was in need of a single locus. In the areal sketch, with Market Street seen from the south, a struggling confluence of a grid system – typologically void of a center, and romanticized imagery derived from medieval European towns, can be recognized. Here, it is as if Kahn tries to paste a chain of concentrically placed objects on the existing, rectangular grid – a mismatch, while the solids themselves also appear oversized, blocking any view of the space behind. The result is a collection of seemingly unrelated Platonic solids of different kinds (a truncated pyramid; tubular towers), that in their saturation subdue that which already exists: the City Hall on the left, and a small flock of buildings on the right, intentionally made miniature. What we have here is an uncanniness, a scale of unrealistic proportions that confront us; blatant geometries wherein one can only imagine a figure like Piranesi to be drawn into its cellars. Acting as “servers of form,” those parking towers are in fact less opaque than one would first suggest: they are made of a concrete post-beam construction, leaving the facades open and allowing cars to pass through them below (fig. 9).19 Lifted on pilotis and covered with a roof garden, it is unclear if this Corbusier-inspired machine has any other allotted functions, apart from being a gigantic 1500-cars-per-unit parking garage. Here, Kahnʼs attempt is ambiguous: representation and utilization do not seem to coincide.

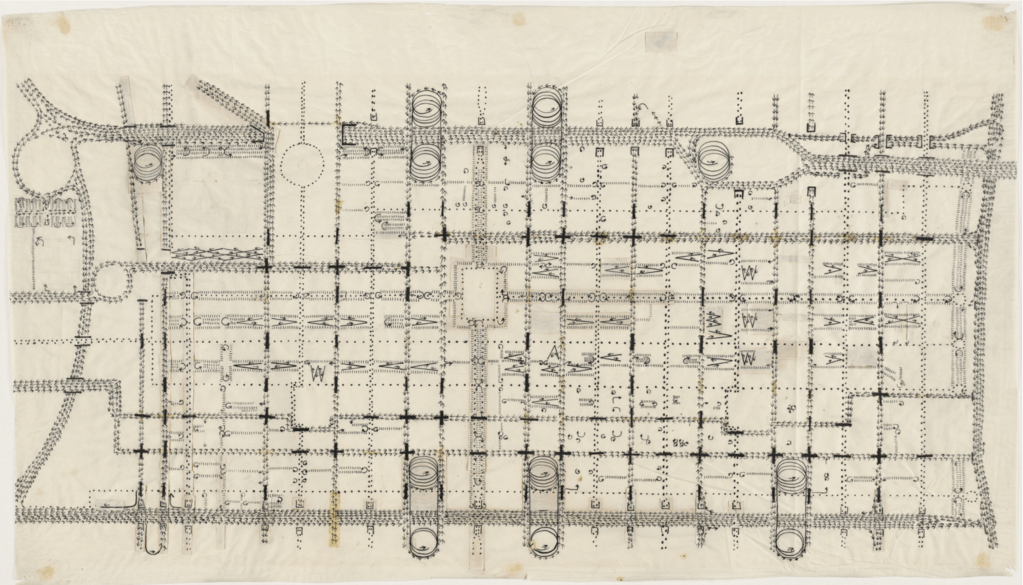

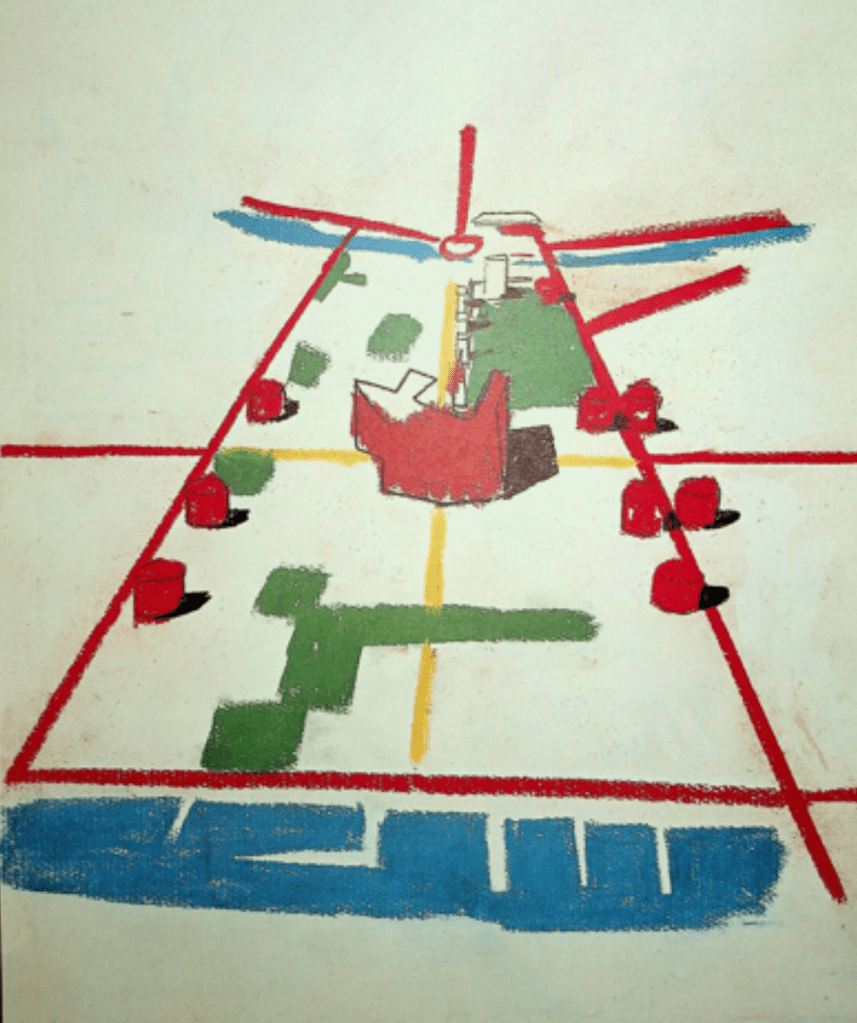

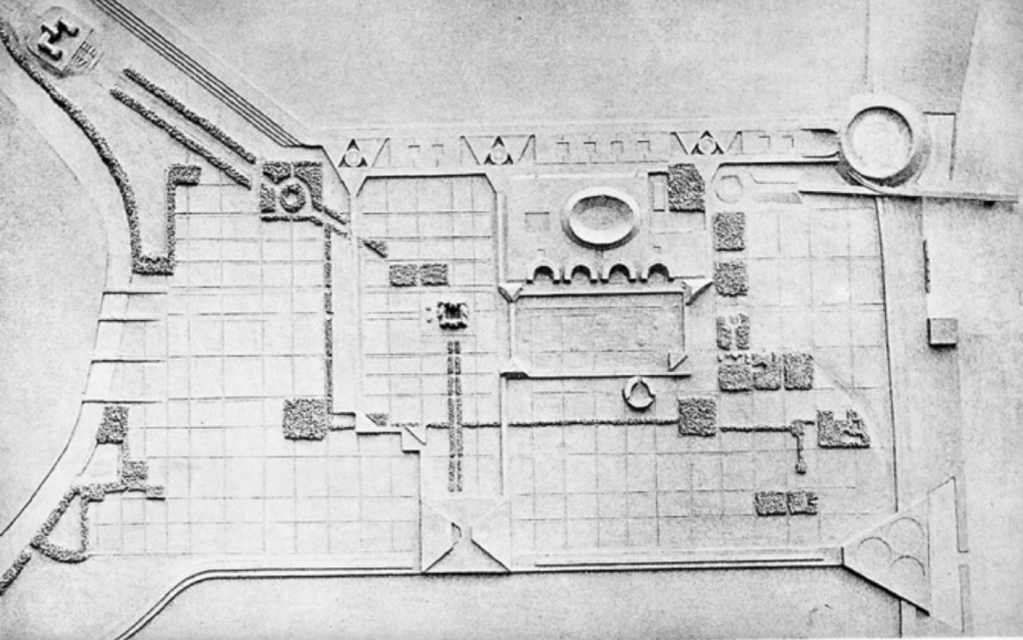

The unrealistic depiction of a new Civic Center east of the City Hall is confirmed if we see the worked- out traffic plan Kahn developed for the entire Midtown area, designed between 1952-53 (fig. 10). The seven cylindrical solids closely grouped in the first drawing are in this case spread out, sporadically situated along two east-west axes and marked by spiraling arrows that move upwards. It is in this traffic plan that Kahnʼs ideas do actually incorporate a certain realism. If we look at a simplified version, drawn from the same angle above the Delaware river, we can see how in the middle sits a large red object, which represents City Hall on Central Square (fig. 11). The yellow lines that appear in cross shape are envisioned as pedestrian walkways, while the red lines on the periphery are allotted to the automobile. Visitors would have to park their cars in the red parking garages – drawn rather small in this instance – and continue on foot. If we look at a more detailed plan of the traffic pattern (fig, 12), the two types of streets are by Kahn entitled as Fast ʻGoʼ circulation and Slow ʻStaccatoʼ circulation, the latter obviously designated for pedestrians. Kahn believed that by making this distinction, the efficiency of street movement would increase considerably.20 The two axes crossing Central Square function as the main shopping boulevards, with most of the other parallel streets also denoted as pedestrian-only. While the original quadrant squares of Pennʼs original plan appear unrecognizable, they are actually connected by a second, inner ring for automobiles. To highlight the division of streets more efficiently, fig. 13 shows one of the rectangles within the grid layout, before and after Kahnʼs imagined alterations. In the proposed plan, automobile streets are only situated in one direction, with the perpendicular streets allotted to pedestrians. By removing an entire lane – situated in the middle, parking and loading are managed outside the pedestrianʼs sight, allowing the buildings to be fully oriented toward the shopping streets. In Kahnʼs plan, the divisions of pace were actually metaphorized by rivers, canals, and docks; represented by automobile, pedestrian, and cul-de-sacs respectively, arrived at via harbors ‒ the parking towers.21 Whilst the reason for such analogies remains unclear, it did provide him with a sense of organizational hierarchy. Overall, we can say that the reorganization of the movement pattern into a traffic-free city center makes the parking towers less alienating. However, apart from a handful sketches of Market Street (with a two-storied boulevard), the quality of street life remains unclear in Kahnʼs plans: we can only imagine the shadows left behind by those megastructures.

System and Attack

Having shown two entirely different sets of drawings: rational traffic patterns integrated and made realistic in the context of the existing urban fabric, yet absent of any form of monumentality, and overly- romanticized recollections of medieval townscapes that do not match with the site ‒ as monumental as can be, the next phase of our analysis actually links the better parts of those two endeavors: Penn Center and the City Tower Project (1951-58) and the Market Street East Studies (1960-1963). Both studies respectively focus on the western and eastern sections of Market Street, intersected by Central Square. The latter, and also the last phase of Kahnʼs studies, was undertaken after he left his position as Master Planning Consultant. It is also structurally different to the traffic pattern earlier discussed, in which the emphasis is laid on the two main arteries of Market and Broad Street. In the new plan, a sense of place is enhanced by the fact that the long, pedestrian boulevard was dismissed: “building in a line represents movement and not arrival,” Kahn said.22 The struggle of superimposing his parking towers concentrically on a grid, as we have seen in the aerial view of Fig. 8, was in Kahnʼs Market Street East studies overcome. Here, he developed an altered traffic system that supported a more bottom-up understanding of spatial containment. While material is again limited and plans do not mention the location of all its institutions, the traffic pattern and the geometries that are read on plan offer enough to grasp how this form could have operated. In fig. 14 and 15, we can see a plan view of a model, showing the proposed redevelopment area within the same limits as originally planned, and a new traffic pattern.

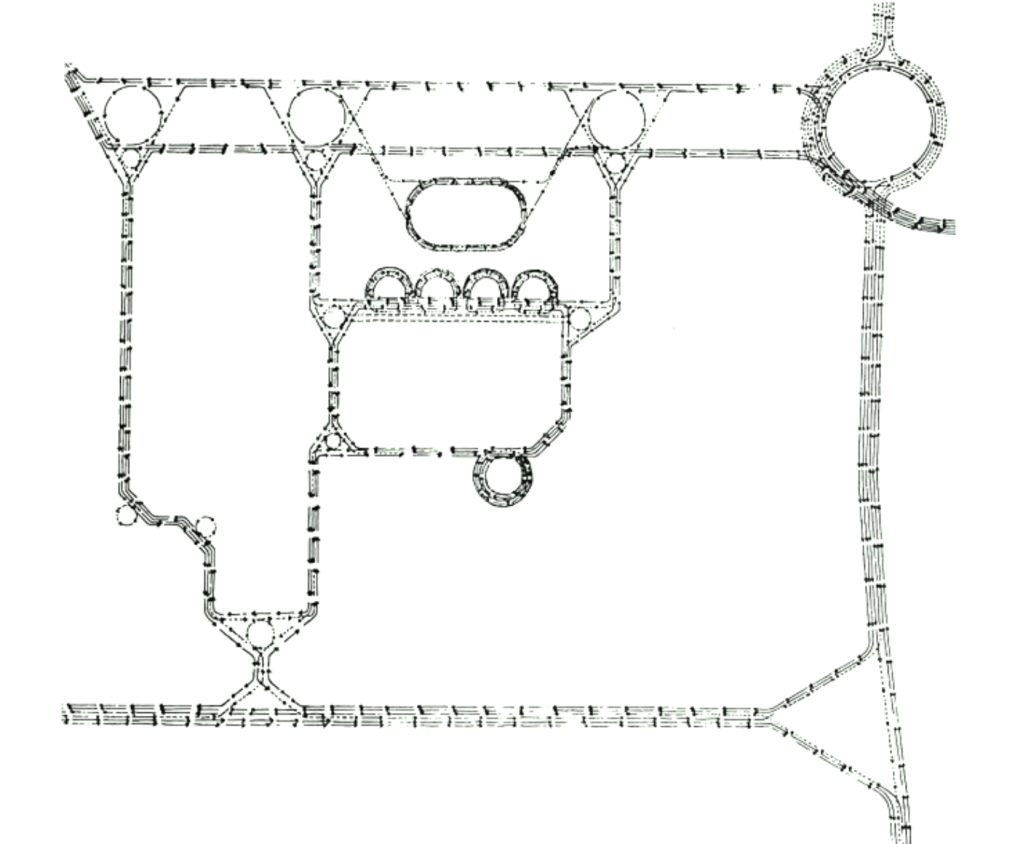

Spatial containment is first and foremost realized by means of a new typology, which includes altered versions of the parking towers from the previous decade, his so-called Viaduct architecture, of which Kahn speaks: “I feel that the time has come to make the distinction between the Viaduct architecture of the car and architecture of manʼs activities. The Viaduct architecture enters the city from outlying areas,” to which he poetically adds that this ʻnewʼ typology is actually a street “which in the center of the city wants to be a building”.23 Whilst similar typologies can already be seen in early twentieth century Futurist visions of Antonio SantʼElia, making it by no means a ʻnewʼ thing, Kahnʼs type was imagined as a multi- storied arcade wall, accommodating different modes of transportation: cars, trucks, and busses elevated above, with shops and terminals and pedestrian street levels. Envisioned as intermediate to street and building, and only existing on the periphery of city centers, “the Viaduct was Kahnʼs attempt to systematize walled-service bordering facilities to define, form, outline and edge the city at the same time”.24 In the plan view we can see how the arcade wall is situated on the same east-west axes the parking towers stood before, yet now articulated in a way more angular and geometrically diverse. Between Franklin (N-E) and Logan Square (N-W) (the former is only vaguely highlighted by a circle), the north side is bordered by an arcade in which three parking towers are housed, as was the case in the previous plan. Reconfigured as such that the towers are now framed by triangular forms that are part of the Viaduct, the line continues around its periphery, forming a roundabout in the north-east corner, a triangular intersection in the south-east corner, and another composition of triangular shapes located on Broad Street, opening up to City Hall in the north. The additional traffic pattern shows how the geometries that appear in plan actually follow the forms indicated by the expressways and are intensified by Kahnʼs masses: they form the monumental corner posts of his urban containment. Inside this frame we can, in turn, see a second ring ‒ shaped by lanes of greenery, highlighting Pennʼs original plan of 1682. In other words, and what can also be seen in the fortification processes of medieval towns, a former city-wall is replaced or enveloped by a heavier and geometrically more sound structure. As mentioned before, the only thing clearly dismissed in the new plan is Market Street itself, which is now replaced by a large geometric oddity. Supposedly a stadium, a new institution of sport and health, a center of recreation, topped with roof garden facilities, the actual function of this shape remains ambiguous. What we do know, however, is that it is by Kahn imagined as an entrance gate, reached via the three adjacent parking towers, and opening up to a Forum in the south: a new center surrounded by civic institutions.25 While this supposedly multi-leveled plaza was never worked out in detail, it gives us a sense of Kahnʼs classicism and his attempt to inject the city of Philadelphia with its own Roman Forum, set within a collection of ordered geometries that rebel the twentieth century decline of the singular, urban core.

On the other side of City Hall, there sits Penn Center, another one of Kahnʼs proposals, developed prior to Market Street East. We will not dive too deeply into the urban dimensions of this plan. Yet, we will focus on a particular building, that is ‒ like his Viaduct architecture ‒ intended to systemize architecture to a degree that it may expand into the urban dimension, and so obscure the border between these two practices. While this attempt did not labor much fruit, the design of the City Tower and its Plaza do bring up a valuable topic of discussion. Penn Center, which follows the original linear arrangement of buildings chained along the Market Street boulevards, is at its most eastern section flanked by the New City Hall (fig. 16). Imagined as a “dematerialized crystal set above an all-material base,” the project brings to mind Bruno Tautʼs Stadtkrone [City Crown], a cityʼs highest point, visible for all people.26 Given the fact that this exaggerated form exceeds the height the neighboring spire of the current City Hall, it remains unclear how the new and old version of the same typology are to be related. In spite of its seemingly awkward location on the boulevard, taking a closer look at the manner in which the building actually meets the street level by means of a stereotomic pedestal (fig. 17), we can see how this attempt does capture the formal, monumental qualities of Kahnʼs earlier parking towers, not as an isolated, self- contained mechanism, but as something which intends to reach its urban milieu. It is with this base- volume that Kahn has found a fitting translation of the monumental forms that shape his romantic chimera, into a context where it could actually be amplified.

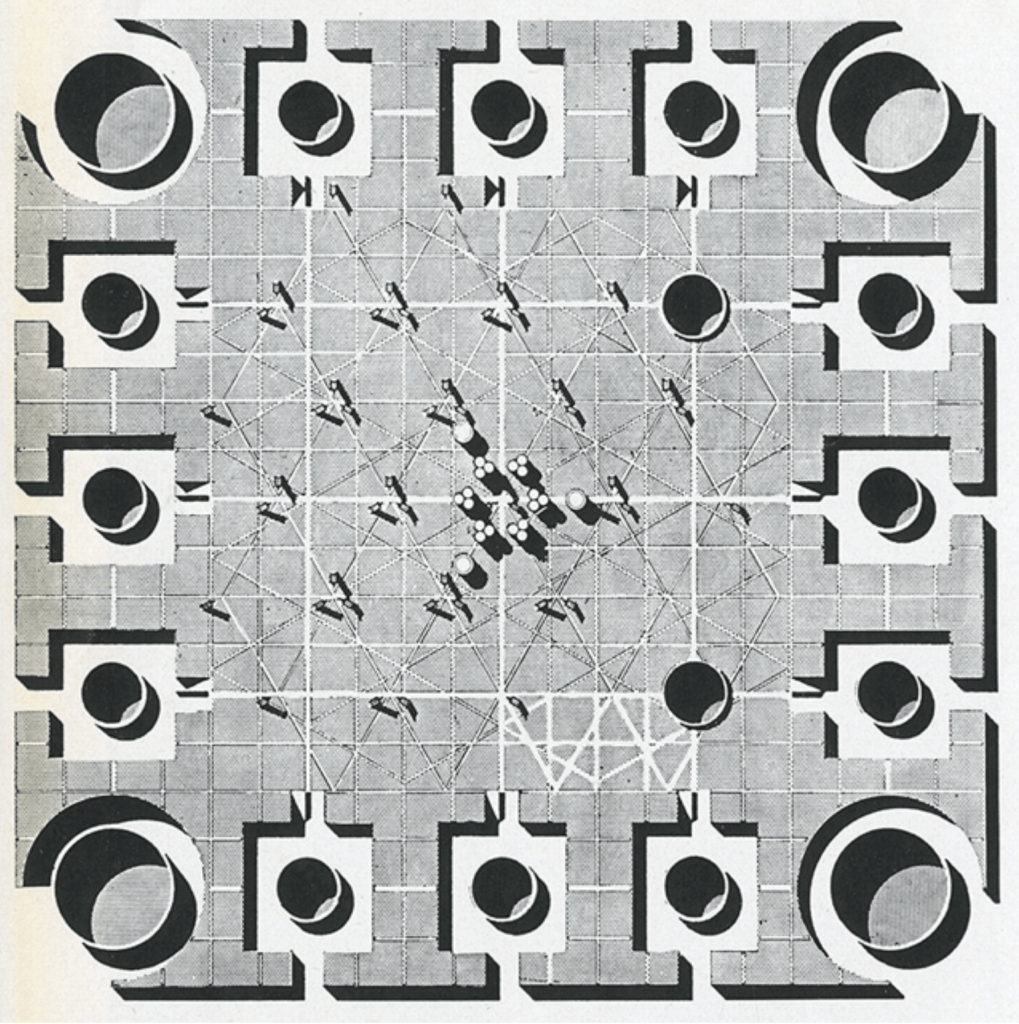

The plaza is composed of three levels: a shopping concourse at street level, a pedestrian plaza above, and a below-grade parking and service level. The large circular shapes in the corners, which serve to bring light and air to the lower levels, are surrounded by ramps that lead the traffic into the parking area below, while the remaining twelve shafts on the periphery serve a different purpose: they are lined with shops and lead the pedestrians to the plaza above (fig. 18). Where it at first seems that the City Tower is not part of the actual plan of fig. 17, closer observation reveals that the different dots are actually the columns of the tower, and the mosaic design of diagonal lines projections of its structure. In other words, one can simply move unaltered over the plaza without having to enter the building, until the point where the columns are grouped close enough to shape an enclosing space. The thick shadows cast by the cylinders, and the plaza itself, again provide Kahnʼs drawing with a thickness, an explicit monumentality. While this base appears solid, the tower itself is, like the parking towers, of a post-beam construction. The inability to correspond utility and representation in the cylindrical towers, seems to be overcome in the design of this project: its fluid, multi-facetted form elevates and is elevated by the skeleton frame. Designed in collaboration with Anne Tyng (1920-2011), whom Kahn worked with for twenty-nine years, the project begun in 1952, following an experimentation with a tetrahedral spaceframe, pulled upwards into a multi-storied tower. Inspired by the triangular and spherical structures of the American architect, engineer and philosopher Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), whom Kahn met in Yale earlier that period, the City Towerʼs spaceframe was by Kahn envisioned as a system that could expand into the scale of the “mega-urban form”.27 With the service functions located in the vertical support shafts and in the post-beam junctures, Kahn could realize an open plan that was “non-directional,” and so implied to him a “democratic accessibility discouraged in monuments of the past”.28 Like Fullerʼs dome, which was believed to develop into one-town communities, 29 Kahn saw his system as a form open to growth, a Structuralist attitude that after the electron microscope appeared commercially in the late 1930s, embraced a collective search to derive and articulate design-systems from molecular structures. While the opposition between the open skeleton and the solid base is effective, the towerʼs polygonal shape does appear out of context in Kahnʼs scheme for Midtown Philadelphia, especially in relation to a skyline consisting of various Platonic solids. Also, the fact that this building is presented as the New City Hall seems to be an added retrospect, awkwardly situated next to a building of the same function. Though, the inventiveness of the tetrahedral system and the manner in which pedestrian street-life is guided into its interior through several theatrical gestures, shine light on an intense experiment fueled with historical symbolisms, that can only propel oneʼs interest to enter this galactic stage.

Louis Kahnʼs Plans for Midtown Philadelphia exist in contradiction. The early phases of his studies pose strategies that intend to seize control over the automobile, Kahnʼs main antagonist – the destructor of form. In this act of rebellion, he draws upon his nostalgia: medieval defense mechanisms merge with civic institutions, a confluence that poses gaps: representation and utilization substitute each other but do not seem to go hand in hand. In the latter phases of his studies those dichotomies are slowly overcome: movement patterns start to shape the geometries of his monuments; they are not strangers anymore. Although the Fuller-inspired spaceframe does not coincide with his usual impenetrable solids, Kahnʼs attempt to develop a system of open growth that could stretch from building to city, takes its most effective shape in the typology of the Viaduct, functioning both as a keeper of form – a defense wall, and an integrative element; they isolate and integrate simultaneously. In the end, it is Kahnʼs own ambivalence with which he dismantles the fortress he had constructed. Yet, we can say that the manifest destiny of his monumental form had become amplified to a certain degree: evolving from an initial focus on tectonic expression to serve a civic, institutional purpose. Kahnʼs Pompeii is a fossil packed beneath a layer of contradictions. Incapable to be seen in full scope, we are at least reminded that we must first pass through its doors.

Unpublished Work © 2023 Joseph Gardella

Ennotes

1 Karl König, The Meaning of Modern Architecture, Lecture, 2 Feb. 1965, Camphill School, Glencraig (February 1965).

2 Vincent Scully Jr, Louis I. Kahn (New York: George Braziller Inc., 1962), 10.

3 Kenneth Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1995), 233.

4 Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, fourth edition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007), 240.

5 Frampton, Modern Architecture, 240.

6 Christian Norberg-Schulz, Meaning in Western Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1975), 207.

7 Non Arkaraprasertkul, The social poetics of urban design: rethinking urban design through Louis Kahnʼs vision for Central Philadelphia (1939-1962), Journal of Urban Design, Vol. 21, No. 6 (June 2016), 732.

8 Heinz Ronner, Sharad Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1977), 11.

9 Scott Knowles, Imagining Philadelphia: Edmund Bacon and the Future of the City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), 8.

10 Louis Kahn, Toward a Plan for Midtown Philadelphia, Perspecta, 1953, Vol. 2 (1953), 13.

11 Non Arkaraprasertkul, Toward Modernist Urban Planning: Louis Kahnʼs Plan for Central Philadelphia, Journal of Urban Design, Vol. 13, No. 2 (June 2008), 178.

12 Ben Adler, Gregory Heller, Ed Bacon: planning, politics, and the building of modern Philadelphia, Book Review, The Journal of the American institute of Architects (May 2014).

13 Knowles, Imagining Philadelphia, 3.

14 Arkaraprasertkul, Toward Modernist Urban Planning, 189.

15 Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture, 223.

16 Ronner, Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74, 28.

17 Stanford Anderson, Public Institutions: Louis I. Kahnʼs Reading of Volume Zero. Journal of Architectural Education (1984-), Vol. 49, No. 1 (September 1995), 13.

18 Scully, Louis I. Kahn, 42.

19 Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture, 224.

20 Ronner, Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74, 26.

21 Louis Kahn, Toward a Plan for Midtown Philadelphia, 11.

22 Ronner, Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74, 31.

23 Ronner, Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74, 31.

24 Arkaraprasertkul, Toward Modernist Urban Planning, 185.

25 Ronner, Jhaveri, Louis I. Kahn: Complete Works 1935-74, 32.

26 Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture, 218.

27 Frampton, Studies in Tectonic Culture, 223.

28 Sarah Ksiazek, Critiques of Liberal Individualism: Louis Kahnʼs Civic Projects, 1947-57, Assemblage, Dec., 1996, No. 31 (December 1996), 70.

29 Ksiazek, Critiques of Liberal Individualism, 67.