An essay on Josef Hoffmann’s Purkersdorf Sanatorium, Vienna (1905)

This study sets out a mission to draw a bridge between two distinctly different disciplines: that of architecture and psychiatry. This bridge is constructed by illustrating two opposing dimensions: a physical and a mental one, where the former is possessed by architecture and the latter by psychiatry. This is the realm in which the story unfolds, it follows a path in between two worlds. During the study, the polarity between those extremes is constantly constructed and simultaneously destructed, with the intention to determine their inseparability. This story is therefore of yin and yang.

We will orient our study towards a time and place where a merging of humanities became a recurring phenomenon: fin- de-siècle Vienna (the turn from the 19th to the 20th century). Architecture and psychiatry are in this study respectively represented by two figures: the Austrian architect and designer Josef Hoffmann (1870-1956) and the Austro-German psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840-1902). Both will be accompanied by their contemporaries, depicting a world of intellects that worked on other sides of the spectrum and still searched for a similar improvement of the human condition. We will analyze how this ideal came into existence, how it shifted and got strengthened by these two opposing worlds. Finally, the study will show how the bridge between architecture and psychiatry finds its structure in ʻhealthʼ, as a point where the two worlds meet.

The first chapter will illustrate the rise of a new, modern identity and its genesis within the Viennese environment. The birth of this phenomenon will be illustrated as a cause of developments within two distant disciplines: psychoanalysis and the visual arts. We will determine how both fields responded to a psychopathological problem that was taking root in modern society and through this act gave rise to a new direction in human self-perception. The second chapter continues on this notion, by illustrating how this change in self-perception evolved into a new Modernist language of design. From here, we will include the field of psychiatric therapy and determine in what way architecture and psychiatry were characterized by a similar desire. The third chapter embraces this meeting point, as it illustrates how both fields sought asylum from modern urban life. We will then continue on this notion and show how Hoffmann and his contemporaries petrified their search for utopia, by creating a model that directly responded to problems posed by their environment. The final chapter, then, dives into the physical properties of this model and examines its underlying design language. This will be done by the use of a case study: the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, a sanatorium for nervous ailments completed by Hoffmann in 1905. In doing so, the final chapter aims to construct evidence in proving the healing potential of Hoffmannʼs model, by defining it as a bridge that connects architecture and psychiatry, that of the body and the mind. This phase will therefore bring the different storylines to a close and formulate an answer on the following research question: How did Josef Hoffmann respond to a psychopathological problem that was taking root in modern society, and how is this response manifested in the Purkersdorf Sanatorium for nervous ailments of 1905?

beneath the skin

When Richard von Krafft-Ebing stressed upon the problems of modern society and its heading for a “moral and physical ruin” in his book ʻÜber Gesunde und Kranke Nervenʼ (1885), he advocated a change that was needed to ʻhealʼ society from a pathological downfall that ‒ in his eyes – seemed inevitable. The modern person, as argued by Krafft-Ebing, is by no means leisurely, calm nor healthy, appearing pale, disgruntled, agitated and unsteady; an observation that was particularly aimed at the inhabitants of overpopulated cities.1 In his eyes, such symptoms are a direct result of an overtaxed nervous system, caused by ongoing stresses that permeate modern urban life. He continues by arguing that the modern man lives in an almost permanent state of irritation and feverish over-excitement, turning back and forth in an extraordinary haste in order to constantly feed oneself with social stimulants and other pleasures that provide short- lived sensations. As a result of this ceaseless exposure to such sensations, man becomes addicted to them and will crave for a more varied and intensified type of stimulant, automatically creating a viscous circle; pleasures have become necessities, consequently resulting in a nervous system that has to do more work in order to find satisfaction and is therefore draining energy and self-confidence. As a result, man can only find comfort in activity and is no longer able to bear a simple and contemplative life. When such a self-destructive process takes grip of the whole strata of the population, one is according to Krafft-Ebing entitled to speak of a ʻnervous ageʼ.2 Although his work excludes context, for it being purely a theoretical model, we are able to draw a line between Krafft-Ebingʼs observations and the environment in which he was active during that time, namely: Vienna. In order to make this connection, Krafft-Ebingʼs theories on nervous ailments should at first be framed within the psychiatric developments that took place during this time. In doing so, the chapter aims to construct an analogy between the psychiatric (and psychoanalytical) developments at the turn of the century and the genesis of a new, modern identity.

Often claimed as being a product of modern civilization, the psychopathological term and nervous disorder ʻneurastheniaʼ became a major diagnosis during the late 19th century, after it was reintroduced by the American neurologist George Miller Beard (1839-1883) in 1869.3 Being a result of the exhaustion of the central nervous systemʼs energy reserves, the condition turned into a popular ʻcatch-allʼ diagnosis that was coined when no physical illnesses were present in the patient.4 This ambiguity shows that during the end of the century, man had become aware of the possibility that illnesses were not limited to somatic symptoms, and were therefore rejecting the Cartesian dualism where physical and mental properties are treated separately. As a matter of fact, it was the rise of psychology, and particularly that of psychoanalysis, that opened up a vast and untreated territory in which the interface of both properties, the body and the mind, could be understood. The figure who was at the forefront of those discoveries was the Austrian neurologist and founder of psychoanalysis: Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Interestingly, in exactly the same year Krafft-Ebing published his work on nervous ailments, Freud was appointed lecturer on ʻnervous diseasesʼ at the University of Vienna, followed by Krafft-Ebing taking on the role as chair of psychiatry only four years later in 1889.5 Although their therapeutical approaches oppose each other; Krafft-Ebing practicing out of a somatic school of psychiatry, prioritizing ʻbodilyʼ treatment, whereas in Freudian psychoanalysis such treatment was not seen as significant on the effect, both colleagues were at the forefront of a psychiatric transformation that took place during the end of the 20th century in the Austro-Hungarian stronghold; questioning both the origin and therapeutical solutions to nervous and mental diseases.

In the case of Freud, the discovery of the interrelation between the psyche and manʼs physical well-being had led to a whole new stratum of therapeutical approaches. In his theories, the psychoanalyst is portrayed as “an archaeologist in his excavations; uncovering layer upon layer of the patientʼs psyche, before coming to the deepest, most valuable treasures.”6 This analogy indicates manʼs rising awareness of the differentiation between the conscious and the unconscious mind: the former containing all thoughts, feelings and memories which we are aware of and can process rationally, while the latterʼs content works outside everyday consciousness and is largely inaccessible, only to appear unexpectedly in dreams or through slips of the tongue; a phenomenon known as the ʻFreudian slipʼ.7 As the psychoanalyst aims to bring the latter to the surface and is therefore seeking confrontation with truths that would otherwise be buried away, one was automatically choosing a path that was not without consequences. In doing so, one had to be aware of the fact that such anxieties were concealed for a reason. Man was simply not capable to confront the mammoth of pain that he had repressed for so long, living in a ceaseless avoidance of his troubles. Hence, the rise of psychoanalysis gave birth to a psychological ambiguity that possessed modern manʼs self-consciousness. While on the one hand, the search for an inner and possibly more truthful self-image was a courageous act that could give man a strengthened sense of identity in a new day and age, it was on the other hand exactly this search that opened up the intangibilities and uncertainties of the unconscious. In other words, the search for a definition of modern identity was automatically leading one away from understanding ʻidentityʼ as something singular, obsolete and easy to attain. In reality, modern identity was ambiguous and complex; being characterized by a “hurrying, scurrying, flickering life” that possesses a manifold of meanings.8 By confronting this ambiguity, one was automatically exposed to his own vulnerability: the very identity he had constructed was actually based on certainty and tradition. The modern man was required to do the contrary, to remove this mask and courageously embrace his spirit from within.

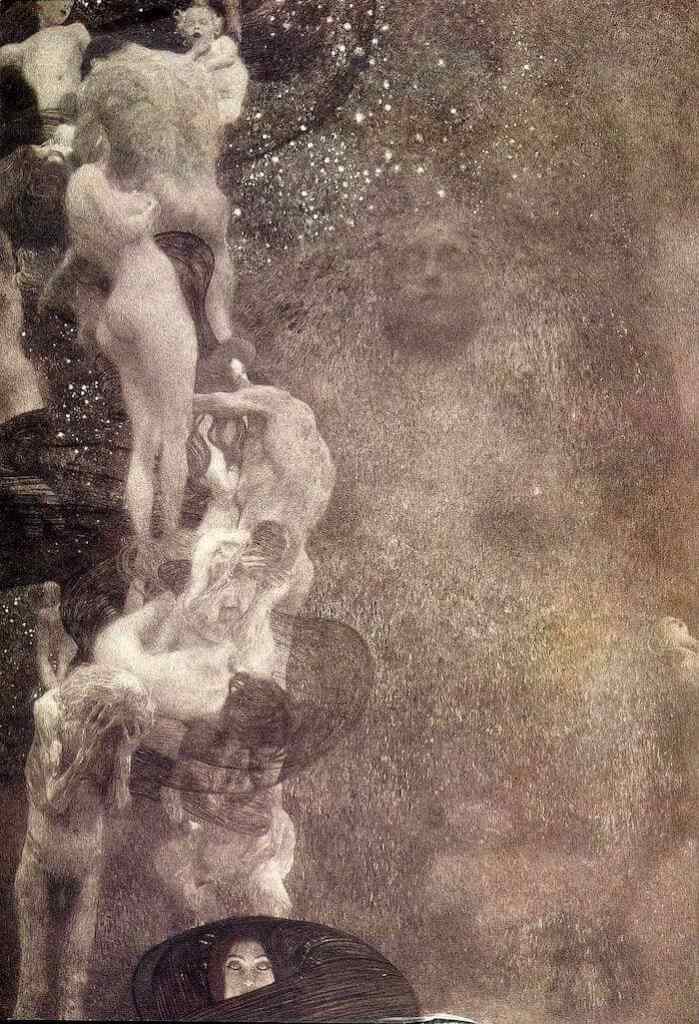

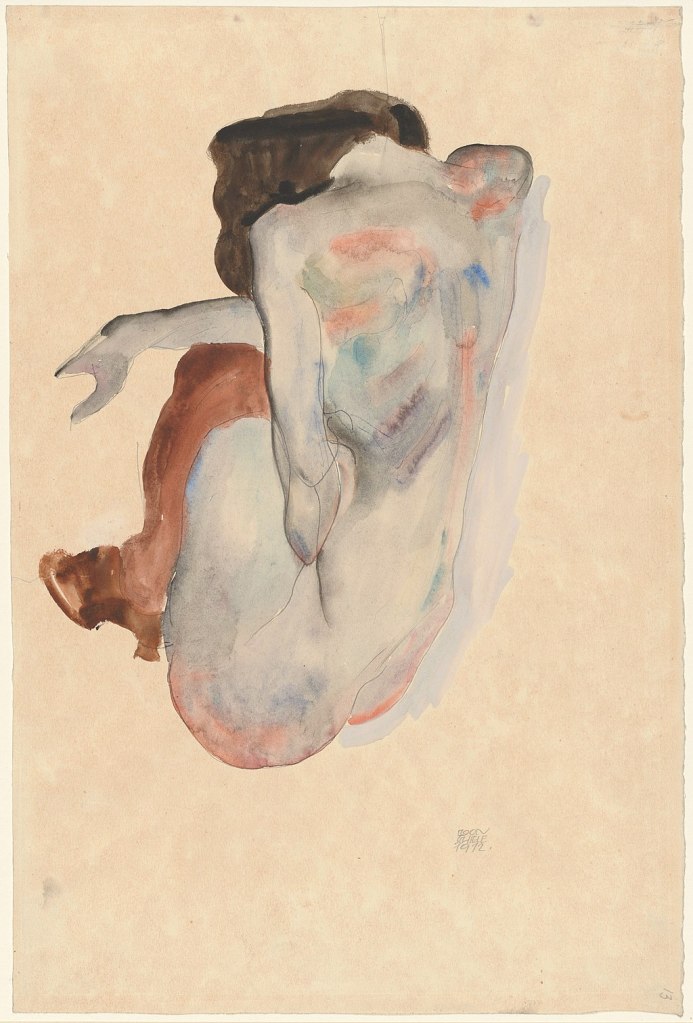

Featured Image: Josef Hoffmann, Purkersdorf Sanatorium, Purkersdorf, Austria, 1904-1905, restored 1995, view from the east. P hotograph courtesy of Klaus. 2: Gustav Klimt, 1898. Nuda Veritas (Detail). Oil on Canvas, 252 x 56 cm. Original in Color. Theatersammlung der Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. / 3: ʻEmbryoʼ. Retrieved from (RD) Reformatorisch Dagblad. Article: “Embryo bezield en daarom beschermwaardig”. Dr. A. A. Teeuw, Drs. C. Sonnevelt. / 4: Gustav Klimt, 1900- 1907. ʻPhilosophyʼ (Photo). Oil on Canvas, 430 x 300 cm (Destroyed). Retrieved from: http://www.gustav-klimt.com / 5: Egon Schiele, 1912. ʻCrouching Nude in Shoes and Black Stockings, Back Viewʼ. Watercolor, gouache and graphite on paper, 48.3 x 32.4 cm. Retrieved from: http://www.metmuseum.org

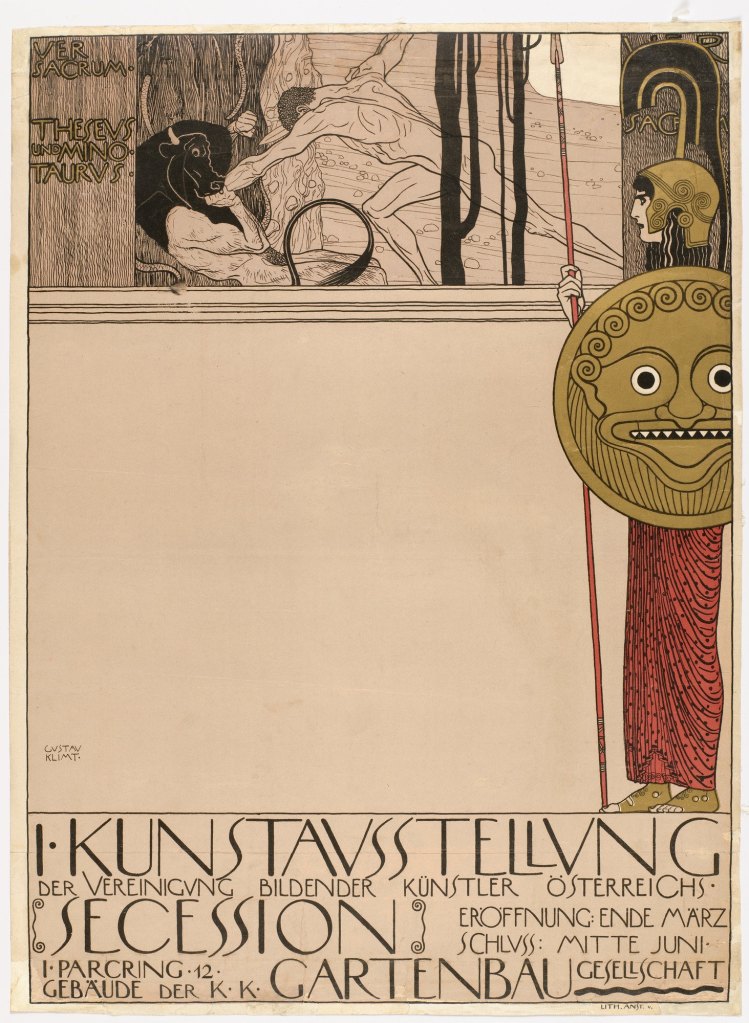

While having discussed the role of psychoanalysis in the formation of a new contemporary identity, this process should, however, be contextualized in a larger socio-cultural situation. As a matter of fact, the introspective journey of the modern man was already taking shape in Vienna during the seventies, when a rebellious group of young and liberal Viennese writers began to gather in a period of social and moral crisis. While this group, known as ʻDie Jungenʼ, started off as a literary movement that challenged “the moralistic stance of nineteenth-century literature in favor of sociological truth and psychological – especially sexual ‒ openness”, their rebellious nature soon spread to many fields of study; including politics, and finally: the visual arts.9 In the mid-nineties, this revolt against tradition started to dominate the course of the arts in Vienna, when a group of artists, architects and designers, known as the ʻSiebener Clubʼ, similarly broke loose from prevailing academic constraints in favor of an “open, experimental attitude toward painting”, aiming to express a new life-orientation in visual form.10 The club soon grew into a forum for the avant-garde, favoring a new, unified and contemporary language of expression. Among the seven members of the association were the artist Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), the designer Koloman Moser (1868-1918), as well as the architects Joseph Maria Olbrich (1967-1908) and Hoffmann himself. It was this two- year-period of intense discussions that eventually resulted in the genesis of a new art movement: the ʻWiener Sezessionʼ [Vienna Secession] (1897-1905), being the Viennese variant of the Jugendstil. Originally, the movement embraced the search for an architectural style that could cope with the new demands of the industrial revolution and the subsequent social problems; one that opposed the approach taken by the ʻWiener Künstlerhausʼ [Vienna Arthous] ‒ Austriaʼs main artists hub – where traditionalism prevailed.11 Often entitled as the ʻfather of Modernismʼ12, the architect and one of the Secessionʼs founders, Otto Wagner (1841-1918), emphasized on the necessity of this ʻbreakʼ with tradition in the following manner: “Art and artists should and must represent their own day and age. Our future salvation cannot consist of merely mimicking all the stylistic tendencies that flourished over the last decades… Art, in its nascence, must be imbued with the realism of our present time.”13 Thus, art had to express the modern man; a new style that would orchestrate the bloom of an unfolding identity. In the first edition of the Secessionʼs magazine ʻVer Sacrumʼ [Sacred Spring] its founder, Gustav Klimt, gave man a glimpse of this new world when he held up an empty mirror to the face of man in his painting ʻNuda Veritasʼ of 1898 (Figure 2). Here, he confronted the beholder with an unguarded frontality, challenging man to gaze into the luminous depth of the mirrorʼs surface and face the naked truth that one would find in its reflection; a kind of confrontation that, according to Wagner, had to be made in order “to show modern man his true face”.14 In this process, the hierarchy between art, as the object of perception, and man, being the perceiver himself, was challenged; turning art into a medium through which one were to plunge into the depths of his own unconsciousness and find introspection. There, behind the mask of historicity that concealed modern man, what would one find? It is this question, indirectly made by Klimt, that finds analogy with the earlier discussed tendencies of Freudian psychoanalysis: to identify and bring the unconscious mind into a state of awareness, one that is buried underneath the many layers of everyday superficiality. It is this particular search for introspection and self-referentiality that shows the first signs of the founding of a modern identity; one that was not seen as something retrieved externally, but rather as a force that grew from within and needed to be uncovered. Actually, we can compare this artistic challenge to the evolution of an embryo (Figure 3), a comparison which was made by the American architect and design theorist Christopher Alexander (1936-) in the following manner: “It is not a process of addition, in which pre-formed parts are combined to create a whole: but a process of unfolding, like the evolution of an embryo, in which the whole precedes its parts, and actually gives birth to them, by splitting.”15 By making this analogy, we are able to argue that the genesis of Viennese Modernism was treated as a ʻnaturalʼ process gradually taking root in manʼs own being, but yet to find physical expression. The aim of the Secessionists was then to articulate a new type of art that would “eliminate the border between interior and exterior”, between the true face of modern man and the eclectic and chaotic mask that covered it. In this reign, it was the artistʼs task to make that bridge a reality; to close the gap between both worlds.

In the case of the visual arts, it was through this merging of the physical and the mental, that artists were to confront the anxieties that permeated modern life. Arguably the most renowned Viennese artist from that time, Klimt, was one of the leading figures who brought this confrontational state into a visual reality. One of his paintings, ʻPhilosophyʼ (1900-1907), being part of a series commissioned by the University of Vienna, accurately reflects how psychoanalysis was translated into a medium of art. Klimt himself, as the artist, had turned into an analyst, seeking to extract and express (negative) mental conditions through physiognomy; a practice of assessing a personʼs inner state through their outer appearance. In ʻPhilosophyʼ (Figure 4), the tangled bodies of suffering mankind are aimlessly suspended in a viscous void.16 They are caught up in a flow of fate, encapsulated by an incomprehensible force that governs human emotion and renders it into a state of perpetual desolation. In the case of the Austrian figurative painter and student of Klimt, Egon Schiele (1890-1918), one finds a similar internal uncanniness that predominates outward expression. In his ʻCrouching Nudeʼ of 1912 (Figure 5), a pale and lean woman turns her back to the spectator, crumpled into a posture that indicates a state of melancholy and grief. In this inward position, the rather colorful pigments that mark the womanʼs skeleton protrude out of a contrasting pale-blueish and agitated skin tone, intensifying the grotesque appearance of her body and consequently that of a distraught state of mind.

In both examples, we are able to trace the direct influence of psychoanalysis on the course of arts in fin-de-siècle Vienna. By thematizing sentiments that usually shimmer below the surface, the artist has now turned into a psychoanalyst himself. He has brought the physical and the mental, the conscious and the unconscious, into symbiosis; a process of making the human skin thinner and exposing the nerves.17 Interestingly, it is exactly this process of thinning the border between what is inside and what is outside, the skin, that became a recurring theme in Vienna during this period, intersecting domains from human self-perception and social behavior to the great variety of creative traits that characterized this vibrant yet fragile city.

the wall as refuge; the wall as the mind

“My heart is empty. The emptiness is a mirror turned to my own face.” – Ingmar Bergman, The Seventh Seal, 1957

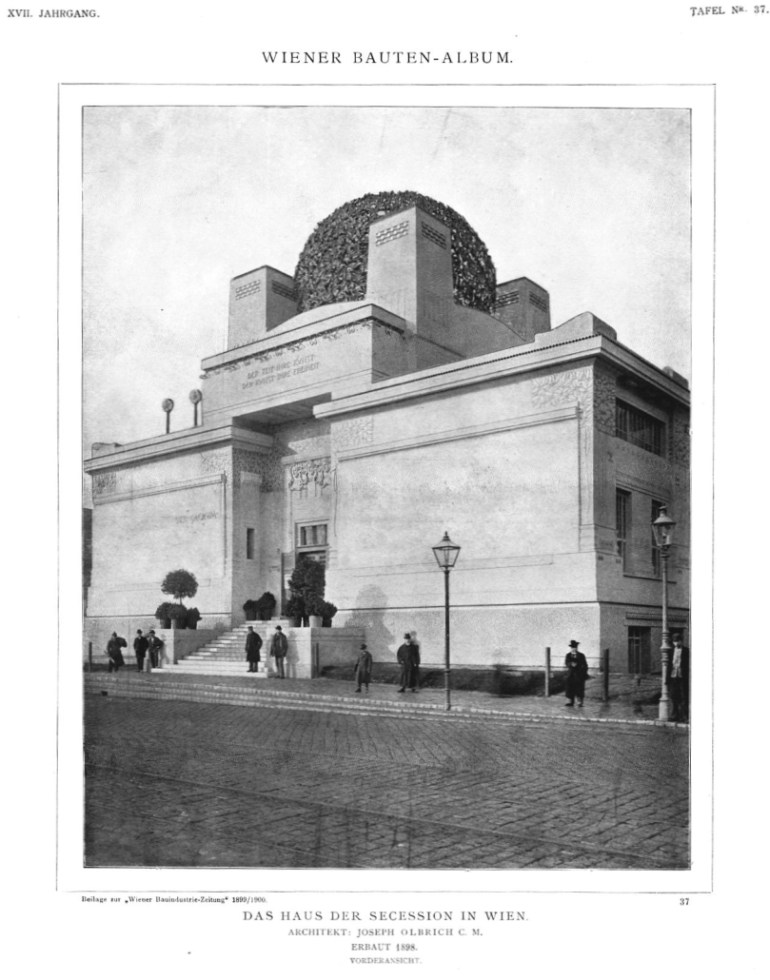

As empty as Klimtʼs mirror is, so is the interior space of the ʻHouse of the Secessionʼ, the associationʼs hub and exhibition hall designed by Olbrich in 1898 (Figure 7). Reflecting the uncertainty that surrounded the concretization of modern identity, this space pioneered the use of movable partitions and therefore justified the Secessionʼs motto: “To every age its art. To every art its freedom.”, which is written above the buildingʼs entrance. Being a place that welcomed the manifold image sought in art, it simultaneously offered refuge from modern urban lifeʼs turmoil, which, as argued by the Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), allowed man “to pause for a moment of inward contemplation and dialogue with our own soul.”18 As discussed, it is this search for introspection that allows us to make a bridge between both psychological and architectural developments. As for the psychoanalyst, the Secessionʼs aim was to remove the mask that suppressed the modern spirit, which was in their case an “obsolete, inebriated mix-up of styles” being of a historicist nature, as argued by Hoffmann in 1897.19 While the former uses a set of theories and therapeutical techniques in order to study the unconscious mind and bring such phenomena to the surface, it was through the medium of architecture (and other forms of visual expression) that the latter intended to bring the modern spirit to the fore. Architecture was in this case used as an ʻinstrumentʼ, a method of working, through which a mental state could be enhanced; an act which can be defined as ʻmodernʼ, since the building (the perceived) is subordinated to its content (the perceiver). Through this process, the attention is automatically drawn away from the building itself as the point of reference; leading to a valuation of an environment in which external stimulants are regulated. In the case of the historicist styles that characterized the Viennese building code, and particularly the ʻRingstraßenstilʼ [Ring Road style] which was developed during the second half of the 19th century, such a sensory overload of eclectic decoration displaces the center point of attention to its appearance and therefore drags manʼs conscious attention outside of the self; prioritizing the ʻmaskʼ as opposed to that which lays behind it. Being the Viennese variant of the Jugendstil, the Secession obviously did not reject the use of ornament in architecture. However, it was through its treatment that the Secessionists portrayed its opposing force, namely: plainness. The duality between both empty and rich surfaces can for example be found in Klimtʼs ʻTheseus and the Minotaurʼ, the poster for the First Secession Exhibition of 1897 (Figure 9), as well as the Façade arrangement of the House of the Secession itself. In both instances, decoration is used in order to frame and accentuate a centralized unadorned plane, once again orchestrating the empty space within. This value was also acknowledged by Hoffmann, who claimed that the bare wall was ʻsacredʼ to them.20 Although conforming to a Jugendstil format, these manipulations can be seen as first signs of a new visual language based on the fundamental thought to regulate external stimulants to a bare minimum in order to create cleanliness and neutrality; turning the object of perception into a refuge for the mind.

Having explained how a Modernist vocabulary started to take shape in Viennaʼs avant-garde scenes and particularly within the course of architecture, we will now determine how this language, being characterized by a yearning for simplicity, became the solution to problems posed by urban lifeʼs ongoing stresses. Furthermore, we will discuss the parallels between a new proto-Modernist architecture and the healing-methods developed in the field of psychiatry; the latter being therapeutical solutions as proposed and executed by Krafft-Ebing.

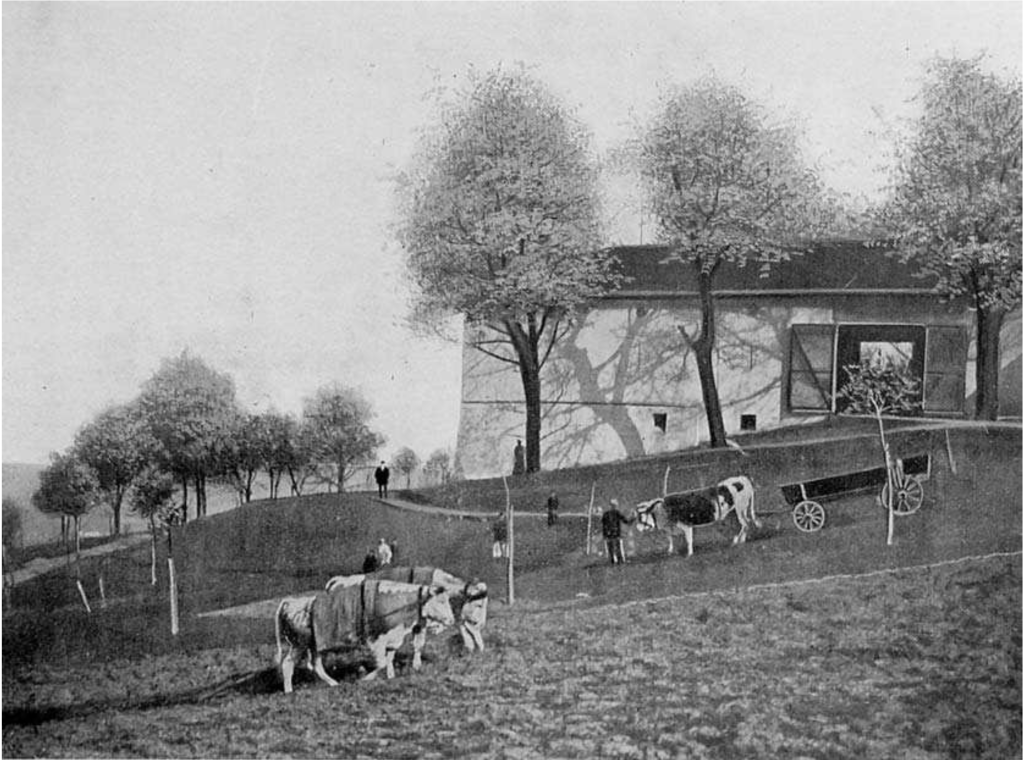

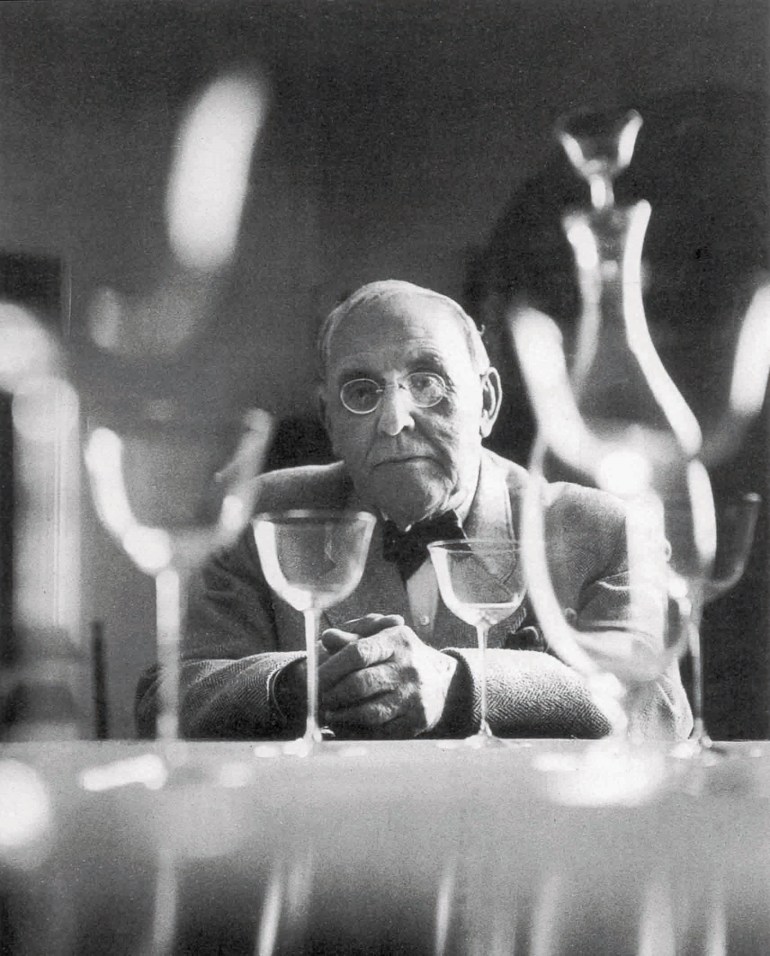

7: Josef Maria Olbrich, 1898. ʻDas Haus der Secession in Wienʼ (Vorderansicht). Photograph Origin: Wiener Bauindustrie-Zeitung 1899- 1900. / 9: Gustav Klimt, 1898. ʻTheseus and the Minotaurʼ, Cover of ʻVer Sacrumʼ. Lithograph. Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. / 10: Photograph of patients at work at the Haschhof Colony. From H. Schlöss, Die Irrenpflege, p. 214, bottom. Bibliothek der Medizinischen Universität Wien. / 11: Josef Hoffmann, Portrait, Vienna. Photograph post 1945, Yoichi Okamoto. Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst/Gegenwartskunt (MAK).

By placing Modernism at the interface of architecture and the human condition, or in other words, by framing it as an orientation that synthesizes both environment (the habitat) and lifestyle (the inhabitant), we are able to read it as a model that opposes ʻfragmentationʼ in favor of ʻintegrationʼ. This parallel is for example seen in the stance taken by the Krafft-Ebing, who like Hoffmann proposed to replace the “old, harmful and chaotic” environment with new surroundings that are characterized by a “regulated simplicity”, in order to live a healthier lifestyle.21 By making this comparison, we are able argue that the changes in the architectural discourse were not limited to aestheticisms but inclined a reform of the human condition. In this sense, Modernism was a cure that could, contradictory, “heal a sick society” from modern life itself.22 In Krafft-Ebingʼs writings, this new environment is perceived and visualized from a psychiatric point of view as it indicates the way in which a therapeutical environment, a sanatorium, should be conceived in order to positively influence oneʼs rehabilitation process. While this model is strictly formulated in accordance with sanatoria and is therefore not indicating a solution on a larger urban scale, we are however able to extract a method of healing and consider it equivalent to the motives that led to the birth of Modernism as an all-encompassing life-orientation. Before we direct our study to the Sanatorium typology, the contemporary developments in both architecture and psychiatry should first be compared. As argued, one of the fundamental principles behind Modernist architecture was to offer refuge from the turmoil of modern life. Interestingly, it was during the same time-period that a new reform-minded social movement came to existence in the German Empire, which is known as ʻLebensreformʼ [life reform]. This movement propagated a simple yet healthy back-to-nature lifestyle and idealized a rural environment over the rising industrialized metropolis; firmly rejecting modern consumerism. Likewise, it was this turn towards a non-urban idyllic life that went hand-in-hand with the developing ideas in the field of psychiatry; to create a self-contained environment where the pace of life could be controlled. In fact, it was in the rural areas of Lower Austria that a great number of psychiatric institutions were realized, based on the integration of agricultural self- sufficiency with the progressive desire for human transformation and rehabilitation. One of these institutions was the ʻHaschhof Agricultural Colonyʼ, established in 1899 in the outskirts of Vienna (Figure 10). This pavilion-style psychiatric institution represented “an important ideological and therapeutical intervention into the care of Lower Austriaʼs mentally ill”23, by embodying the belief that “physical labor and communal ethos would reintegrate their bodies and minds into healthy spiritual wholes.”24 The colony was imagined as a nature-oriented and self-sufficient organism that evolved out of a reform impulse, positing a “pre-industrial rural mode of existence as a potential answer to a set of diverse problems and challenges” rooted in modern urban life.25 Although it obviously came forth out of the early-nineteenth century Romantic belief that nature would be curative, we are able to connect this anti-urban ideology to the tenets of an emerging Modernist lifestyle. In both constructs we can extract the search for an alternate reality that opposes the uncontrollability of modern life. Therefore, both were envisioned as self-contained environments that encompass every aspect of life in order to reform the human condition; to replace that which is uncontrollable with the controllable. With this thought in mind, we will now return to Krafft-Ebingʼs work, whose therapeutical environment accurately reflects this notion. In Über Gesunde und Kranke Nerven, he defines the term ʻsanatoriaʼ as “a combined application of the entire healing apparatus”.26 Thus, the sanatorium is understood as a totally designed and self- functioning construct that integrates different healing processes into a machine-like device; closely resembling the famous ʻarchitecture-as-machineʼ metaphor made by Le Corbusier thirty-five years later. Even though the latter is often recognized as the founder of Modernism, we are able to argue that the first signs of a new environmentally adapted Modernist life- orientation was already taking root in the field of psychiatric therapy years before. In response to an “unpredictable modern urban environment” that constantly threatens the “balance of nervous force in its inhabitants” 27, the sanatorium was by Krafft- Ebing articulated as a predictable, controlled physical environment, “away from the hustle and bustle of the world”.28 So, instead of merely treating the symptoms of nervous ailments, his psychiatric therapy embraces the idea to transport the patient into an alternate reality detached from oneʼs domestic and professional life. We are therefore able to define Krafft- Ebingʼs method as ʻholisticʼ, since it concentrates on “effecting change on an afflicted personʼs entire lifestyle” by subjecting the patient to a therapeutical program that encompasses every aspect of his or her daily life. Returning to the argument that Modernism and psychiatric therapy are grounded by a mutual belief; we will now introduce one of the Secessionʼs founders whoʼs design approach is based on this same search for total design: Josef Hoffmann (Figure 11).

my kingdom is not of this world

a thought

concealed by water

like an island

on a mirror plane

here I stand

detached and silenced

my gaze returning

no thoughts remain

When Josef Hoffmann travelled to the Island of Capri in 1897 and experienced how the simple silhouettes of the white-colored peasant buildings were standing out against the blue-lagoon skies and robust mountain ranges, he was struck by a sense of delight and renewal. “There, for the first time, it became clear to me what matters in architecture”29, a quotation dating back to a lecture of 1911, indicating a turning point in the oeuvre of the young Hoffmann by soundly distancing himself from historicism. In his description of Capriʼs vernacular architecture, he argues that the buildings always form a “whole, self-contained, uniform image”, of which its smooth simplicity is free from artificial overabundance and speaks for “an open, understanding language for everyone”30, as a result of the direct correlation between ʻnecessityʼ and ʻdesignʼ.31 While this description obviously indicates Hoffmannʼs growing affinity for an architectural expression that would eventually become the pillars of the Modernist style, the emphasis on self-containment and uniformity also allows us to see a direct link with Krafft-Ebingʼs ideal sanatorium. In the case of both figures, their visions are determined by the longing for a self-functioning and anti-urban utopianism, believing that “a simply and totally planned environment would be the starting point for a happy and healthier society”.32 Like Krafft-Ebing, Hoffmann was an opponent of the modern metropolis, and his affection for vernacular architecture explains this stance. Being cut off from the mainland and functioning as a self-sufficient entity, the island of Capri symbolizes Hoffmannʼs imaginative reality, and as argued in his ʻSelbstbiographieʼ (1892), it was through these autonomic forms of architectural and environmental unity that Hoffmann found both “escape and means to seek a lost world”.33

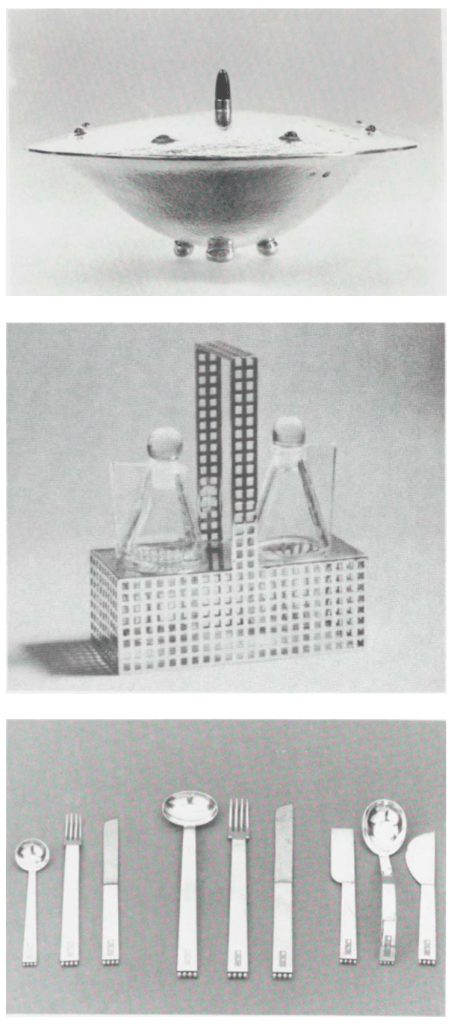

In exactly the same way, Hoffmannʼs interpretation of the new, modern house is defined by this sense for autonomy, claiming that a ʻhouseʼ should “emerge as one piece and that its exterior should inherently reveal its interior”.34 Interestingly, we can reconnect this quotation to a motive identified in the paintings of both Klimt and Schiele, namely the emphasis on ʻthinningʼ the border between inside and outside, that of the skin; being subsequently rooted in the psychoanalytical tendency to bring the conscious and the unconscious mind into a symbiosis. In other words, the inherent spirit of the work had to reveal itself on the outside and reach a state of tangible expression. In the case of Hoffmann, this ʻspiritʼ is understood as an ʻanatomyʼ expressed in every single detail and is therefore synthesizing the work into a total, all-encompassing entity; an inclusiveness that orchestrates everything from furniture to cutlery. Actually, it is this approach to design that seeks the abolishment of the distinct separation between architecture and other fields, since every design scale is grounded by a unified vocabulary; allowing us to once again define fin-de-siècle Vienna as a place determined by the capacity for ʻsynthesisʼ. The necessity of unification among the arts can for example be traced in a statement made by Hoffmann of 1905: “So long as our cities, our houses, our rooms, our furniture, our effects, our clothes, and our jewelry, so long as our language and our feelings fail to reflect the spirit of our times in a plain, simple and beautiful way, we shall lag infinitely far behind our ancestors; no lie can conceal these weaknesses.”35 This quotation reveals Hoffmannʼs desire to create an art form that “comprises all areas of life”,36 one that abolishes the “extant separation of art and life” and intertwines them into an aestheticization of the everyday.37 This orientation shows how he, like the other Secessionists, wanted to harmonize the gradually unfolding modern spirit with the physical world, and in this quest to find the most complete form of gestalt that makes this unification possible. In other words, the great universal work of art would have to synthesize all art genres in order to “represent humanity in its entirety”; a notion which is entitled as the ʻgesamtkunstwerkʼ, literally meaning ʻtotal work of artʼ.38

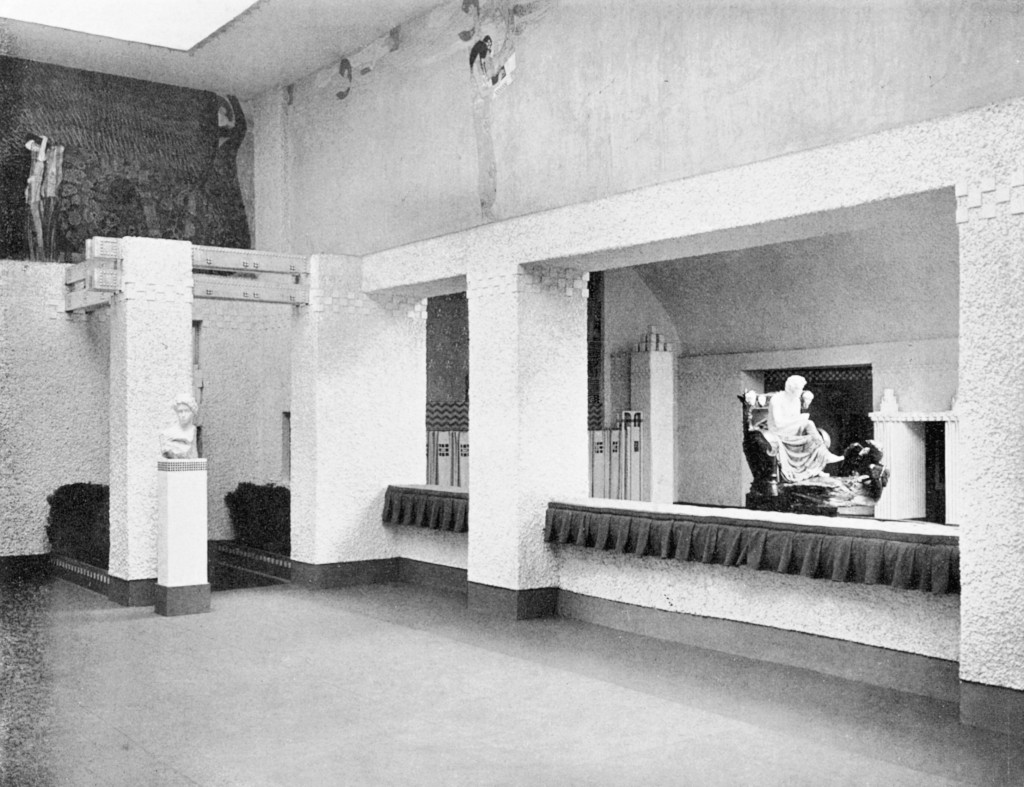

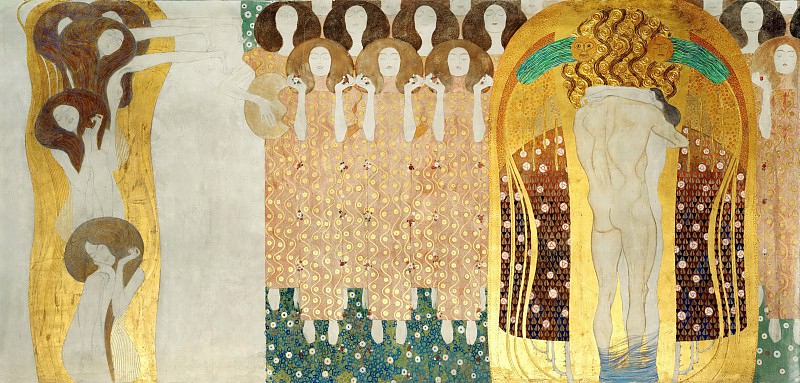

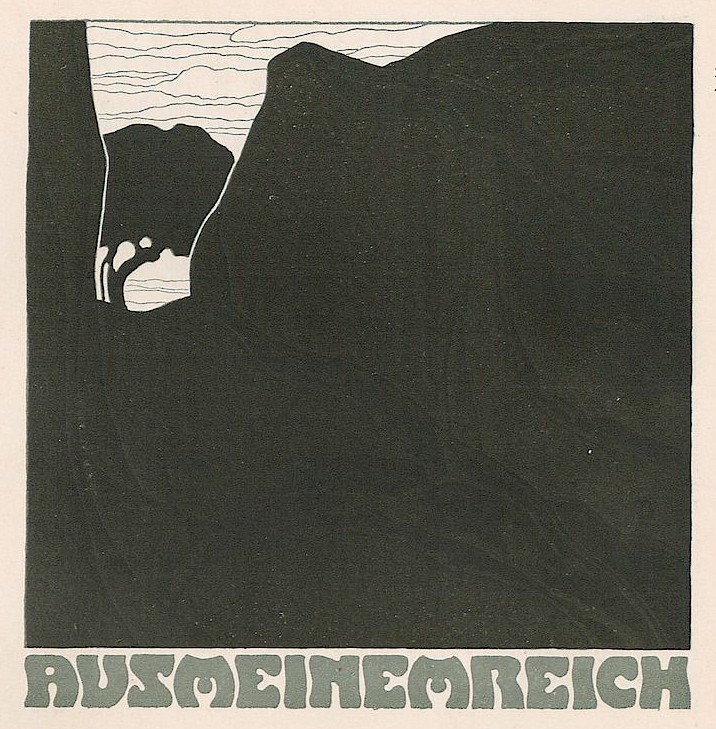

Figure 12: The 1902 Beethoven Exhibition, (XIV). House of the Secession, Interior Shot. View from the left-hand aisle to the main hall with Max Klingerʼs Beethoven statue. Photograph: ʻArchive of Secessionʼ. / Figure 13: Gustav Klimt, 1902. ʻMy Kingdom Is Not of This Worldʼ. Third panel of the Beethoven Frieze. The Arts, Choir of Angels, Embracing Couple. Casein paints, stucco overlays, drawing pencil, applications made of various materials (glass, mother of pearl, etc.), gold overlays on mortar, 2 x 14 m. Source: ʻÖsterreichische Galerie Belvedereʼ. (Measured Elevations taken from ʻGustav Klimtʼs Beethoven Friezeʼ, Peter Vergo (1973)). / Figure 14: Adolf Böhm, 1901. Aus meinem Reich (From my Kingdom), ʻVer Sacrum 4ʼ (1901). 121. Woodblock Print. Unknown Measurements. Retrieved from: The Vienna Secession: Art Nouveau in Vienna and Germany 1895-1918.

Before diving into the origin of this term and the reasoning behind its spread among young Austrian intellects, the significance of the gesamtkunstwerk within the Secession-group should first be illustrated. One of the examples that signifies its importance is the ʻBeethoven Exhibitionʼ, which was realized under the direction of Hoffmann in 1902 (Figure 12). Conceived as an ode to the German composer Ludwig von Beethoven (1770-1827), the exhibition was visualized as an imaginative world, completely devoted to the Beethovenian symphony. The search for an alternate reality can be recognized in the exhibitionʼs catalogue, claiming that “the arts lead us into the ideal kingdom [in das ideale Reich], in which alone we find true joy, true happiness, true love”.39 This ʻkingdomʼ is also pictured by Klimt in his famous ʻBeethoven Friezeʼ, of which the third panel is entitled as ʻMy Kingdom Is Not of This Worldʼ; once again inclining on the distinction between the two worlds (Figure 13). In his frieze, Klimt depicts the kingdom as “not one to be easily attained” and to be reached only after “overcoming an army of ʻhostile forcesʼ lurking in the psyche”. This process closely resembles the confrontational stages to which the modern man was subjected in order to come to grips with his/her unconscious, once again referring back to Freudian psychoanalysis. Those forces are in Klimtʼs paintings rendered as deadly sins that have taken a hold of manʼs conscious being and should be broken if man were to enter his kingdom. Actually, we can connect this iconography back to Krafft-Ebingʼs illustration of modern urban life, particularly the constant craving for sensations that feed an already overtaxed nervous system. Another example that suggests the Secessionʼs search for utopia is Adolf Böhmʼs (1861-1927) ʻFrom My Kingdomʼ, which was published in the Ver Sacrum of 1901 (Figure 14). The world he depicts consists of two dimensions, one that surrounds the spectator at this moment in time and another located at the end of a path, symbolizing both darkness and lightness respectively. As argued by the author Kevin Karnes, one might interpret Böhmʼs work as “an Arcadian vision of earthly bliss, perhaps attainable somewhere beyond the corrupting streets and spaces of the modern urban metropolis”, once again illustrating the existence of another, potentially better world.40 This interpretation strengthens the claim that the direction taken by the Secessionists was weighted upon the constraints of modern urban life; a longing for a reality that always lies beyond the horizon, one that might never be attained.

Having framed the Secessionʼs embracement of the gesamtkunstwerk as the physical manifestation of a utopian idealism, we will now introduce a figure whose oeuvre surrounds this phenomenon and undoubtedly influenced the Viennese avant-garde: the German composer and theater director Richard Wagner (1813-1883). His direct influence on the Secession can be found in his ʻBeethovenʼ essay of 1870, wherein he declared the following: “So does music now break forth from amidst the chaos of modern civilization. Both say to us: Our kingdom is not of this world. Which means: We come from within, you from without; we spring from the essence of things, you from the appearance.” Apart from a direct connection with the third panel of Klimtʼs Beethoven Frieze in terms of its title, the differentiation between an esoteric and exoteric existence is continued in the work of the Secessionists, embracing the notion that the modern spirit can only exist if it, like an embryo, unfolds from within.

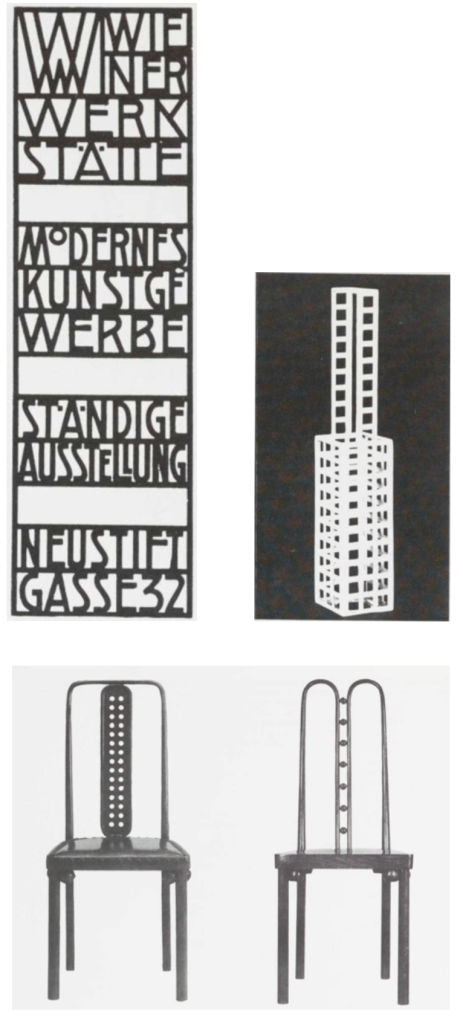

Figure 15 (left): Wiener Werkstätte. Postcard, 1909. Lithography, 14 x 18.9 cm. Fischer Fine Art, London. Figure 16 (left): Josef Hoffmann. Vase, 1905. Painted Sheet Metal, 24.5 cm in Height. Private Collection. Figure 17 (left): Josef Hoffmann. Chairs: ʻPurkersdorfʼ (1904), Wood and Leather, 100 x 45 x 43 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. ʻSieben Kugelnʼ (1906), Wood and Leather, 111.8 x 41.9 x 40.7 cm. Sammlung Tim Chu. / Figure 18 (right): Josef Hoffmann. Bowl, 1903-1905. Hammered Silver, 9.2 cm in Height, 20.3 cm in Diameter. Private Collection. Figure 19 (right): Koloman Moser. Vinegar & Oil Set, 1904-1905. Silver and Glass, 17.2 cm. Private Collection. Figure 20 (right): Josef Hoffmann. Cutlery for Lilly and Fritz Wärndorfer, 1906. Middle Set: Spoon, 21.8 cm, Fork, 21.6 cm, Knife, 21.5 cm. Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst/Gegenwartskunt (MAK). Figure 15-20: Wien 1900: Kunst, Arkitektur & Design, 1987.

Being the one who gave gestalt to the notion of the gesamtkunstwerk and transformed it into a (post-Christian) religion/life-orientation, Wagner sought to synthesize poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts into a unifying whole, aiming for an integration of the arts and theater. Out of his inspiration for the ancient Athenian way of rendering artistic genres in a combined “communally enacted drama”, as stated in ʻDie Kunst und die Revolutionʼ [Art and Revolution] (1849), Wagner desired to create an artform that would embrace modern German culture in its totality.41 He attempted to realize such an environment, when he founded the ʻBayreuther Festspieleʼ in 1876. This German theater festival was an attempt to recreate the Athenian festival, where an entire community emerged itself in art, far from the distraction of the large cities and in a peaceful and secluded environment. This anti-urban construct exemplifies his search for a total work of art that creates and is created by a sense of community wholeness. In ʻDas Kunstwerk der Zukunftʼ [The Artwork of the Future] (1849), Wagner continues on this notion by arguing that “the individual spirit, striving creatively for its redemption in nature, cannot create the artwork of the future. Only the collective, infused with life, can accomplish this.”42 Thus, in Wagnerʼs eyes, the “great gesamtkunstwerk” is a communal endeavor wherein each of the members brings his unique expertise into the work. Interestingly, it was Hoffmann who, after the breakup of the initial Secession-group in 1905, created such a network of specialists and like-minded people. Together with his former acquittance Koloman Moser and the patron Fritz Wärndorfer (1868-1939), he founded a movement known as the Wiener Werkstätte [Vienna Workshop] (1903-1932) (Figure 15). Inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement, the Werkstätte was an anti-industrial collective that consisted of artists, designers and craftsmen who were dedicated to the idea of “the individually made, unrepeatable object”, bringing together a traditional method of manufacture and a distinctively avant-garde aesthetic (Figure 16-20).43 Their emphasis on artistic freedom and a rather democratic approach to product-making, where artist and craftsman have an equal share and creditability in the design process, was a response against a heavily industrialized environment marked by the absence of human imprint. Dedicated to the production of modern decorative arts, the Werkstätte sought to create a unified craft-based aesthetic, a trademark, wherein the applied and the fine arts were “conceived as a unified whole”.44 Therefore, we can interpret the Wekstätte as a means for Hoffman to manifest a design language that would embrace his search for the gesamtkunstwerk and construct a reality that, unlike many utopian visions of that time, could be petrified.

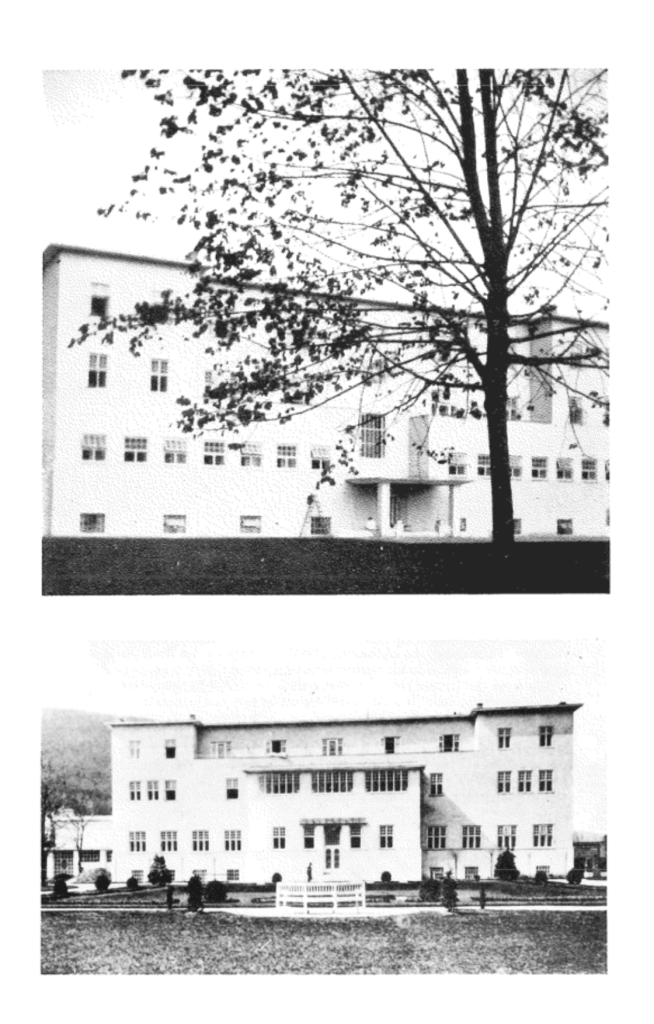

echoes of a new life

This final chapter is a study into the physical properties of Hoffmannʼs first complete architectural ʻgesamtkunstwerkʼ, namely the Purkersdorf Sanatorium (Figure 22, 23), which was completed in 1905 and is located in the municipality of Purkersdorf, a wooded area in the outskirts of Vienna. Being a sanatorium for nervous ailments, the institution is known as the first totally designed and collectively planned building formed by the Wiener Werkstätte. Moreover, the sanatorium can be read as a physical manifestation of the cross-section that exists between the two figures that have taken a prominent role in this study: Josef Hoffmann and Richard von Krafft-Ebing. In other words, the continuous search for an interdisciplinarity between architecture and psychiatry, that of Modernism and therapy, finally finds physical prove in this building. By bringing the storylines to a close, this case study aims to determine the curative properties of the gesamtkunstwerk and therefore the direct relationship between environment and health. In doing so, we will start off by introducing a phenomenological concept known as ʻreverberationʼ, which was conceived and analyzed by the French psychiatrist and phenomenologist Eugène Minkowski (1885-1972), in his work ʻVers une Cosmologie: Fragments Philosophiquesʼ (1936). The excerpt on the following page is taken from Minkowskiʼs work and functions as empirical evidence in the understanding of the interface between physical and mental phenomena. From here, we will claim that Hoffmannʼs sanatorium follows this notion, consequently allowing us to read the gesamtkunstwerk as a model that enables the potential of improving health through the domain of architecture.

“If, having fixed the original form in our mindʼs eye, we ask ourselves how that form comes alive and fills with life, we discover a new dynamic and vital category, a new property of the universe: reverberation (retentir). It is as though a well-spring existed in a sealed vase and its waves, repeatedly echoing against the sides of this vase, filled it with their sonority. Or again, it is as though the sound of a hunting horn, reverberating everywhere through its echo, made the tiniest leaf, the tiniest wisp of moss shudder in a common movement and transformed the whole forest, filling it to its limits, into a vibrating, sonorous world.” – Eugène Minkowski, 1936

In Minkowskiʼs phenomenology45, the notion of ʻreverberationʼ is understood as a dynamic origin of human life, an impulse which spreads through and engulfs both time and space, mind and matter. He communicates the working of this force by making use of two metaphors that illustrate its operation within the material world: the sealed vase and the hunting horn. Yet, it is by illustrating its substantial properties, that a metaphysical interpretation of the term is contemplated. Following Henri Bergsonʼs (1859-1941) notion of the ʻélan vitalʼ [vital impulse] as the driving force of life, Minkowski describes it as an element which keeps man in touch with a feeling of “participation in a flowing onward”, or in other words an inclusion of an inner consciousness in an outer, all-encompassing continuity.46 He later returns to his metaphors, by arguing that because of the very fact that the vase and the forest fill up with sound, they form a “self-enclosed whole, a microcosm”. Therefore, the realization of such a ʻmicrocosmʼ is a result of this very reverberation, and as argued by Minkowski himself, it is this pulse that appropriates everything and breaths into it “its own life”. So then, in exactly the same way, it is this phenomenon that gives birth to and orchestrates the most primal expression of the gesamtkunstwerk, for it being a physical manifestation of manʼs attempt to mimic natureʼs profound ability to create the greatest of integrities, one from which not a single element can be deviated. In taking this stance, we may ask ourselves, what is Hoffmannʼs architectural equivalent to this reverberating pulse? The answer to this question is the ʻleitmotivʼ (leading motive), a term which is in original musical terms known as a recurring figure, fragment or succession of notes. Interestingly, the origin of the leitmotiv is, like the gesamtkunstwerk, associated with the compositions of Richard Wagner, which allows us to once again construct a direct link between his work and that of the Secessionists. Returning to the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, we will now focus on Hoffmannʼs treatment of the leitmotiv, for it is expressed through different formal, spatial and functional layers; creating a total work, that like Minkowskiʼs vase and forest, transform it into a vibrating, sonorous whole.

Figure 21: Joseph Gardella, ʻechoes of a new lifeʼ, 2021. / Figure 22: Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Exterior Shot ʻWest Façadeʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 23: Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Exterior Shot ʻEast Façadeʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985.

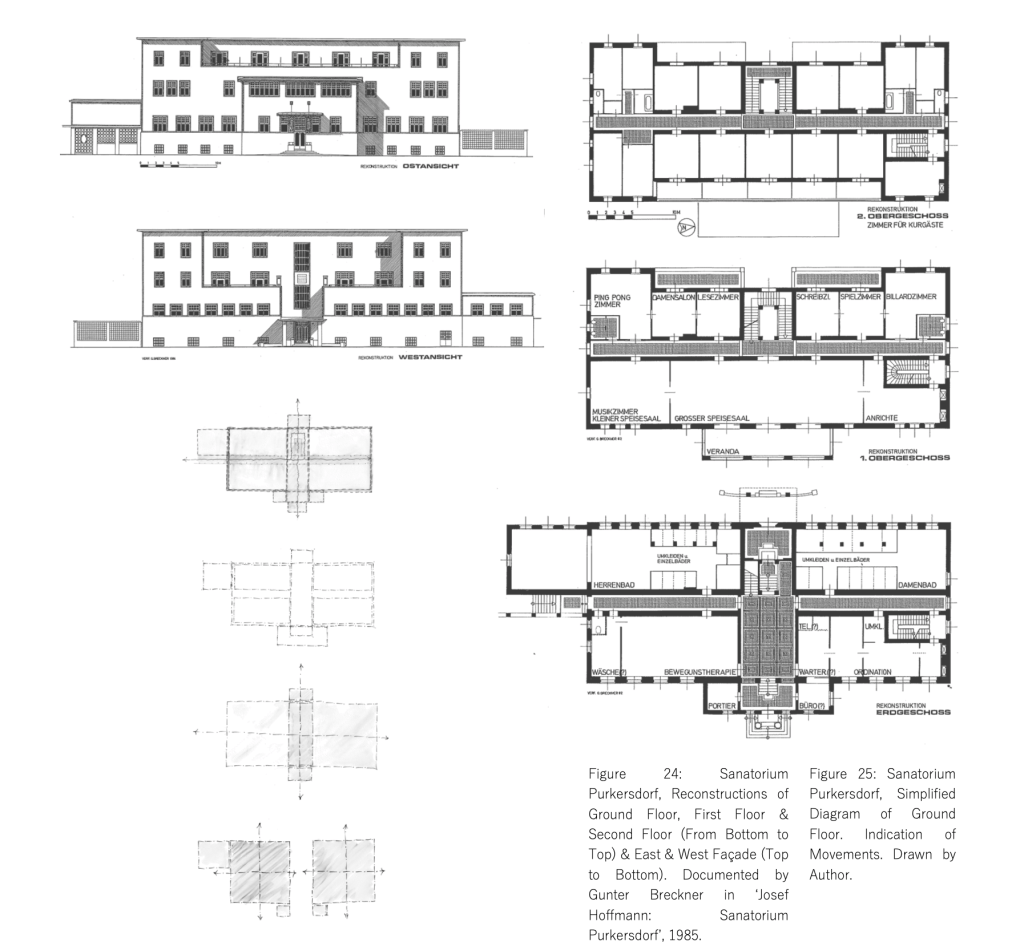

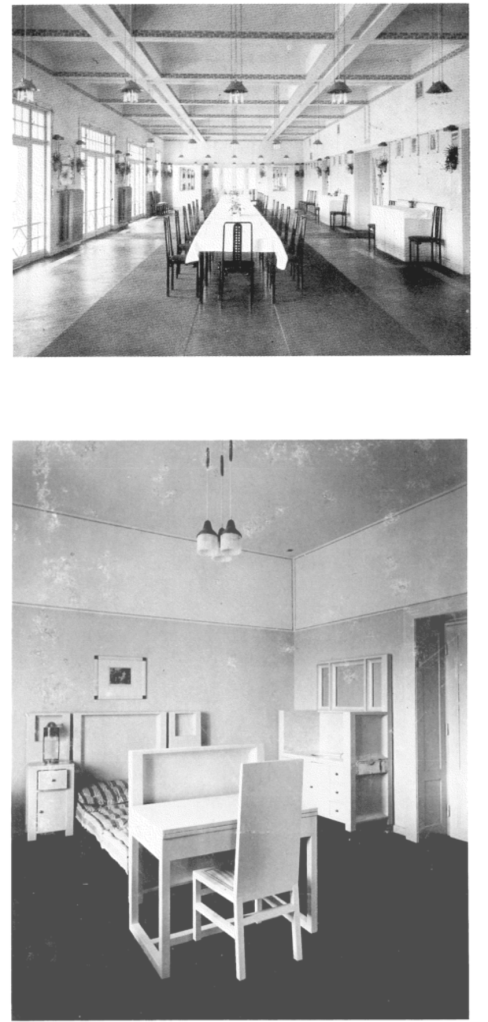

In 1890, together with the physician Anton Löw (1847- 1907), it was Krafft-Ebing who founded the Purkersdorf Sanatorium in a “densely wooded rural area, away from the hustle and bustle of the world”, as prescribed in his work on nervous ailments of 1885.47 Purkersdorf was one of several sanatoria Krafft-Ebing established during the end of the 19th century, that focused on the treatment of nervous diseases such as neurasthenia and hysteria. After his death in 1902, the sanatorium kept on following Krafft-Ebingʼs methods and was eventually bought by the businessman and art collector Viktor Zuckerkandl (1851-1927). In recommendation of his sister-in- law and art critic Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps (1864-1945), who had a close relationship with the Secession, Hoffmann received the commission to design a new ʻkurhausʼ for the sanatorium.48 The new building was conceived as a “cross between a modern hotel and a modern therapeutical center”, that combined various curative methods into an all-embracing architectural program with an emphasis on offering the (wealthy) clientele both comfort and luxury.49 Based on Krafft-Ebingʼs theories, the building emerged as a totally designed, predictable, simple and self- contained environment, that was planned around a therapeutical regime to which the patient was subjected. This systemized approach was holistic, since the patientʼs daily life was “closely monitored” and arranged in order to construct a new lifestyle that would heal the patient over time. In order to rectify the nervous weaknesses caused by an unhealthy unregimented lifestyle, the building was divided into segments devoted to sleep, eating, therapy and leisure.50 This parting of functions is ordered by placing treatment, therapy and utility rooms on the ground floor, leisure facilities on the first floor and the patientʼs private rooms on the top floor (Figure 24). Communal and private domains are thus vertically separated, whereas each floor is subsequently divided into smaller rooms that occupy different ʻepisodesʼ of the therapeutical program. In the same way, the size of each room indicates the amount of time spent in that particular space, while a succession of rooms reflects the sequential order of the program. By ordering the spaces around a centralized corridor and staircase, and by placing them in a direct spatial relationship with the exterior, the patient receives a maximum amount of daylight during different phases of the day, while constantly persisting clarity and guidance throughout the building. The structed temporal division of the program, as prescribed by Krafft-Ebing, was thus made concrete in Hoffmannʼs design; creating an environment that through its geometrical order protects the patient from “surprising shocks to the nerves”. As seen in Figure 25, the buildingʼs plan can be stripped down to two basic elementary forms, the square and the rectangle, that multiply and overlap in orthogonal directions. The ʻsquareʼ is, as its form suggests, used as a directionless territory (like in the private dwellings), whereas the ʻrectangleʼ connects them and implies a direction in form. While this geometrical distinction is a basic design principle, we are able to trace this notion all throughout the building. Letʼs for example direct our attention to an interior shot of the dining room, which is located on the first floor and opens up to a veranda of the east façade (Figure 26). What is immediately striking, is the repetitive consistency between construction, wall enclosure and furniture. The reinforced concrete ceiling beams, which are exposed all throughout the building, brace the entire room in a harmonious coordinate system of horizontals and verticals. Apart from its structural purpose, the beams indicate the spatial and functional orientation of the room, which can be seen in the way the two longitude beams, doubled and separated by a groove, align with the carpet underneath. This mirroring effect creates a spatial frame around the dining table and is therefore making it the focus-point of the room. Thus, by spatially accentuating the roomʼs function, which is in this case ʻdiningʼ, the patient finds visual guidance in order to perform this activity.51 Similarly, the patient bedrooms, of which the interiors were designed by Moser, are formed according to a strict integrated geometry where the bed becomes roomʼs main focus (Figure 27). The limited amount of free space that surrounds the bed and the roomʼs general size suggest the shortage of time the patient is ought to spend there.52 As described earlier, Krafft-Ebingʼs therapeutical program exists of separate phases that are each devoted to a single activity, allowing the patient to ʻmeditateʼ on that activity and become less distracted by other stimulants. The building is in this case a tool in managing the realization of such a singular state of mind. Actually, we are able to connect Hoffmannʼs emphasis on ʻvisual guidanceʼ to the work of his teacher and fellow-Secessionist Otto Wagner, who came up with a similar solution in his design for the ʻPostal Savings Bankʼ of Austria, which was built during the same years. The floor pattern, as pictured in Figure 28, indicates the principal direction of movement and was a direct reaction against, what he would call, “the painful uncertainty” of an anonymous and rapid modern world that lacked a distinct orientation.53 In the case of the sanatorium, we can find a more direct link in the dining roomʼs wall decoration. The stenciled leaf friezes, which define the ceiling cassettes horizontally, continue in a downward direction above the roomʼs entry and exit (Figure 29). This particular detail reminds the patient how to enter and depart and thus embraces the same notion.

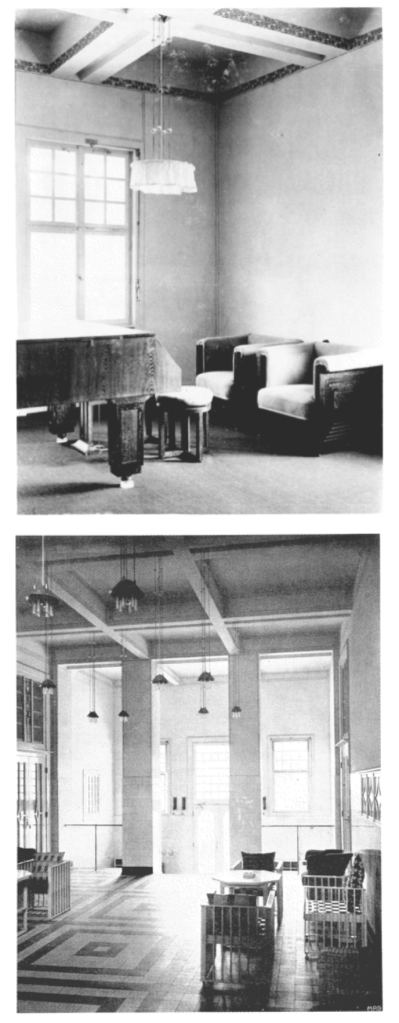

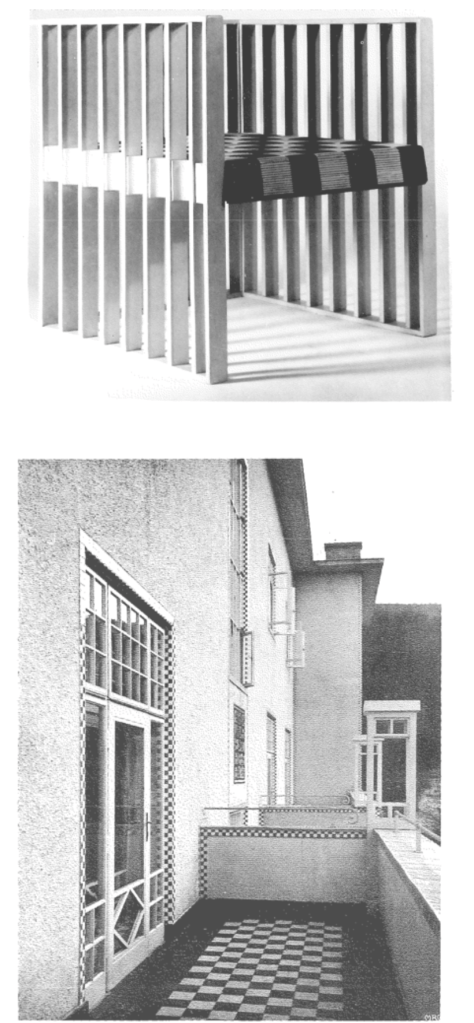

In all of the above examples, we are able to trace the ʻperformanceʼ of the space back to a basic metric system that consists of horizontal and vertical lines, square and rectangular surfaces, as well as cube and cuboid volumes, wherein each of those three dimensions is respectively part of the other, creating a self-referential vocabulary of geometrical entities. This interrelation between elementary forms results in a spatial continuity, since every domain is a succession of the other, or in the words of the architect Peter Behrens (1868-1940), “dependent and related to a higher totality”.54 As seen in an interior shot of the music room (Figure 30), each subdivided shape or space is emphasized individually by marking the outlines of its territory, which is in this case done by stenciled friezes and miniature tiled outlines on the walls. In doing so, the emphasis is constantly laid upon the empty space within each fragment, which as seen in the House of the Secession, allows the observant to find a ʻframeʼ in which the mind can ʻdwellʼ. So, by accentuating the elementary forms that exist within the continuity of line-shape-volume, a rhythm between identical patterns becomes visualized. This repetition is then continued into different design-facets (e.g., furniture, lightning and cutlery) and is thus the ʻpulseʼ that reverberates throughout the sanatorium; creating a work in which a pattern of form is echoed into the tinniest of details. If we trace this patterning back to the basic polarity of the metric system, that of horizontals and verticals, we are able to extract a tension that through its opposing nature constitutes a vital balance among forces. Or in other words, through contrast harmony is achieved (yin and yang). This patterning of contrasts can for example be seen in the entrance hall of the sanatorium (Figure 31), where different opposing forces come to the fore. Here, the planarity of two- dimensional surfaces contrasts with the tectonic appearance of the coffered ceiling, while the plainness of those surfaces also counterpoints the delicate elements of the room. Shallowness and depth, as well as vastness and intimacy are thus experienced simultaneously. Further correspondence between elementary forms can be found in the way the vertical rung structure of the Moserʼs white wooden cubic seating matches the proportions of the concrete columns, as well as the long narrow strings of the centrally ordered lamps. These features therefore strengthen a sense of ʻheightʼ, while the gradual alteration of rising floor levels on the other hand orchestrates a sense of ʻdepthʼ. Though, the most direct expression of this interrelation between contrast and rhythm can be found in the roomʼs decorative motifs. As seen in the figure, a black and white tiled floor pattern is applied throughout the hall and mirrors the exposed ceiling beams above, which in turn communicates with the woven chequerboard pattern of Moserʼs seating (Figure 32). The latter is further repeated in the narrow decorative strips of blue and white tiles that outline the blank surfaces of the façades (Figure 33), as well as the floor tiles in the central corridors and staircase. All these patterns unite into a self-referential network of ʻpulsesʼ, wherein each extreme directly communicates with its counterpart; automatically constructing a balance of forces. Now, if we connect this observation to the ʻvitalistʼ belief that disease results from an imbalance of inner forces ‒ which is in line with Bergsonʼs notion of the ʻélan vitalʼ ‒ we are able to read Hoffmannʼs gesamtkunstwerk as an attempt to revitalize this ʻanatomicalʼ balance in the patients by subjecting them to an environment where a union of polarities is thoroughly applied. The repetitive nature of polarities then becomes a ʻmeditativeʼ experience, which is further enhanced by the reflective interplay of light and empty wall-surface; creating a luminous atmosphere that eases the senses and transposes the patients into a self- contained and white-painted washable world.55

Figure 26 (top far left): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻDining Roomʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 27 (bottom far left): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻGuestroom Second Floorʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 28 (top middle left): Otto Wagner, 1905. The Austrian Postal Savings Bank, Vienna. Interior shot of the ʻKassenhalleʼ. Photograph: Stephen Lewis, 2016 (Date of Post). Retrieved from: Bubkes.Org / Figure 29 (bottom middle left): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻDining Roomʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 30 (top middle right): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻMusic Roomʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 31 (bottom middle right): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻMain Hall to the Eastʼ, Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 32 (top far right): Armchair, 1903, Prag-Rudniker, painted beech, caned seat. Design by Koloman Moser. Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985. / Figure 33 (bottom far right): Sanatorium Purkersdorf, Interior Shot ʻTerrace First Floorʼ, West Façade. Photo Documentation by Gunter Breckner in ʻJosef Hoffmann: Sanatorium Purkersdorfʼ, 1985.

Now, having examined the physical properties of Hoffmannʼs gesamtkunstwerk we are able to determine the healing abilities of an environment that aims to mirror an ideal state of mind. As illustrated in the first chapter, the discovery of the interrelation between manʼs physical and mental well-being led to an alteration in terms of human self-perception. In order to improve the former, one had to come to grips with the latter and examine the interface between both, the conscious and the unconscious mind. Introspection started to outweigh extrospection; a turnaround that led to a depreciation of outward appearance in favor of an inner and potentially more truthful domain. For this reason, the border between both worlds had to be eliminated; to seek that which lies behind the mask of everyday consciousness. The Secession was in this case devoted to creating a new type of art that would reflect this new sense of self. The visual emphasis on ʻemptinessʼ can therefore be seen as a direct result of a shift in attention from an outward to an inward contemplation; it had turned into a mirror for the mind. Art therefore transformed into a tool that could intertwine the polarity of inside and outside, mind and matter.

The Purkersdorf Sanatorium was formulated in accordance with this change, being conceived as a physical projection of an ideal mental state that is based on a vital balance among forces. Thus, in order to treat the patientʼs nervous conditions, it had to be fought by constructing an environment where its counterpart would prevail. The pattern language which evolved out of Hoffmannʼs polarizing metric system is therefore a mirror image of such an ʻanatomicalʼ balance; allowing us to argue that Hoffmannʼs gesamtkunstwerk is an evidence-based design, since it intends to improve the condition of life by physical means. In this process, an interchange between body and mind is set in motion. While on the one hand the psyche projects itself onto physical form, the former is in turn a reverberation of the latter. In other words, mind is an extension of matter, while matter becomes an extension of mind. This observation allows us to interpret the gesamtkunstwerk as an artificial construct that aims to mirror the cycle of nature, a world where body and mind are inseparable and orchestrate the entire performance into an interplay of yin and yang.

Unpublished Work © 2021 Joseph Gardella