An analysis of Paul Scheerbartʼs Expressionist novel: The Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladiesʼ Novel (1914)

The Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladies’ Novel

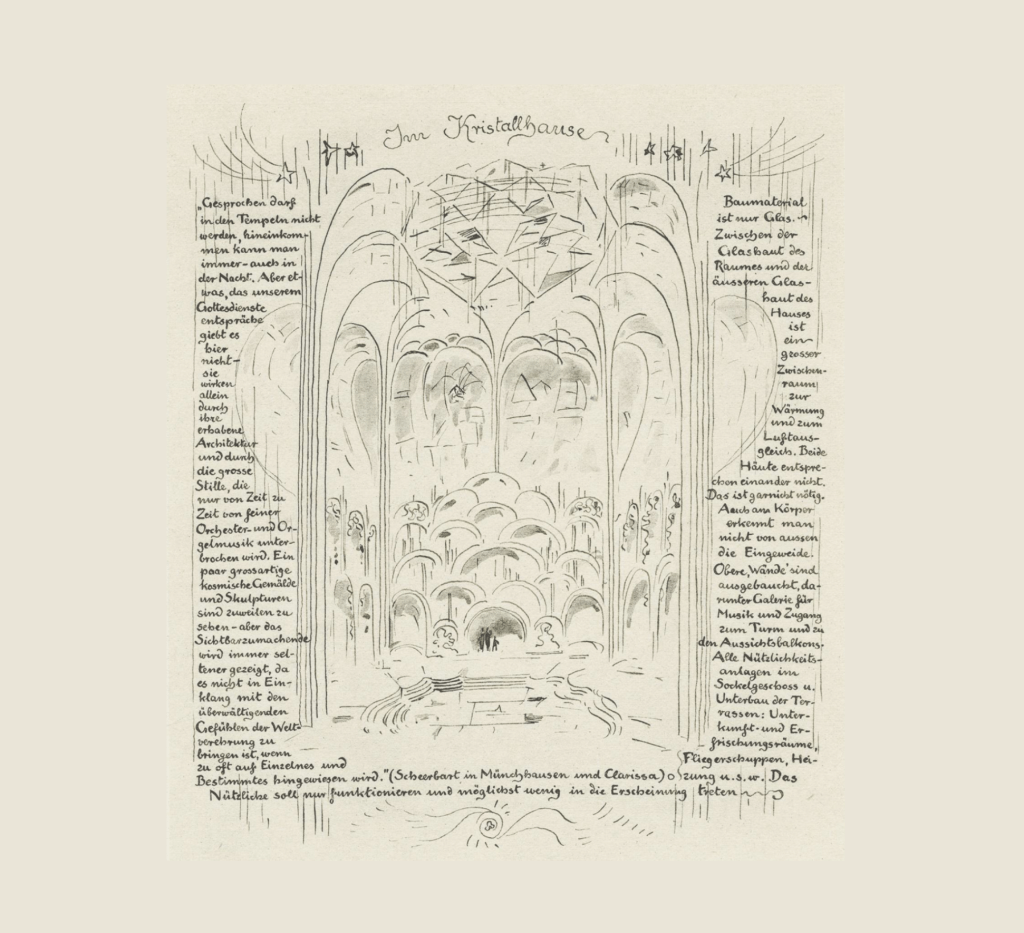

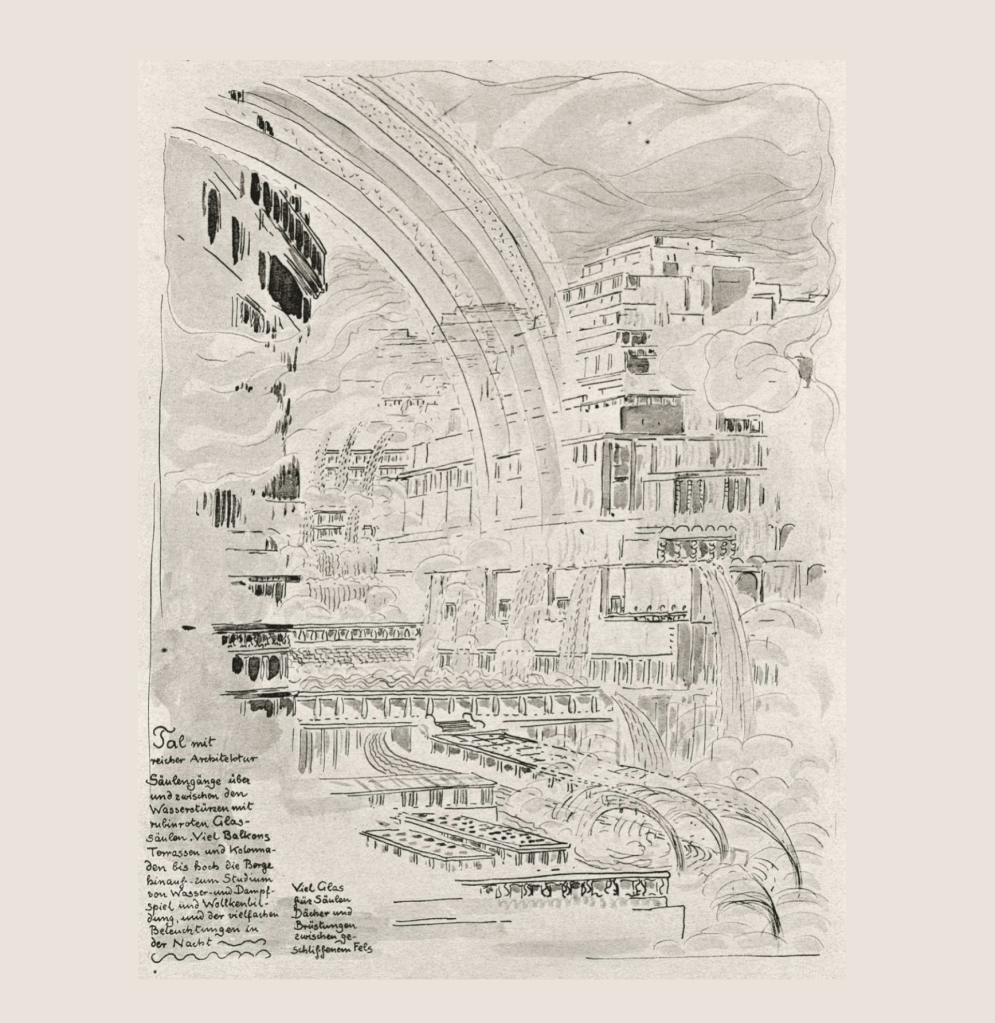

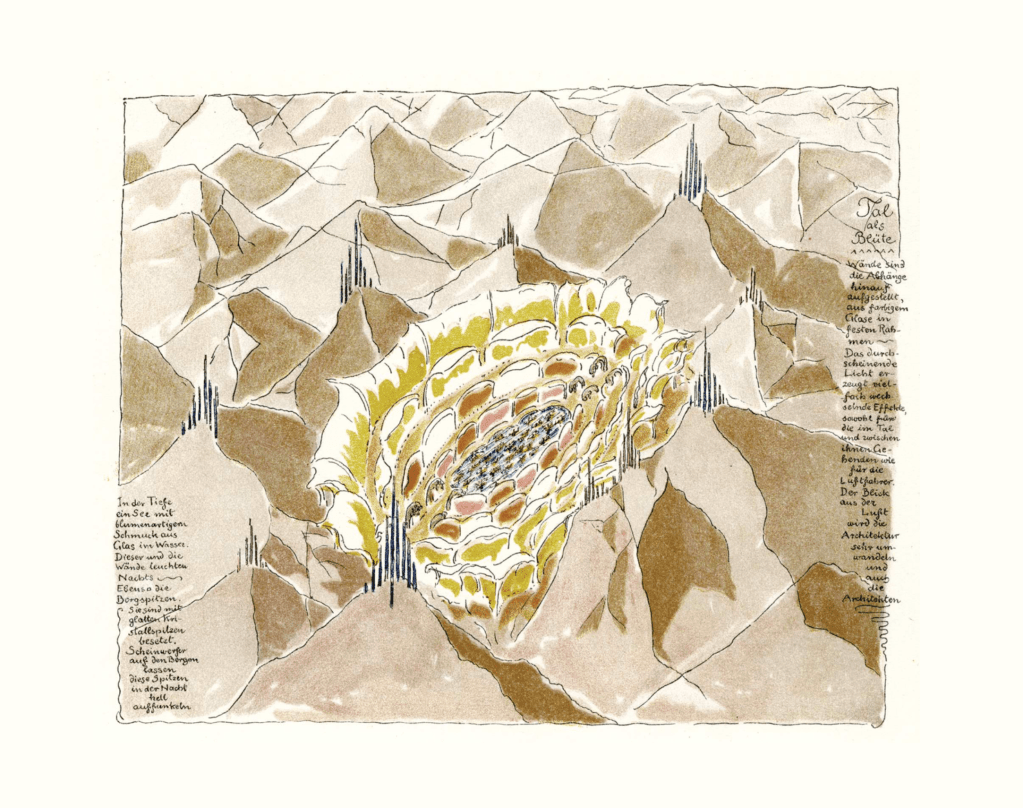

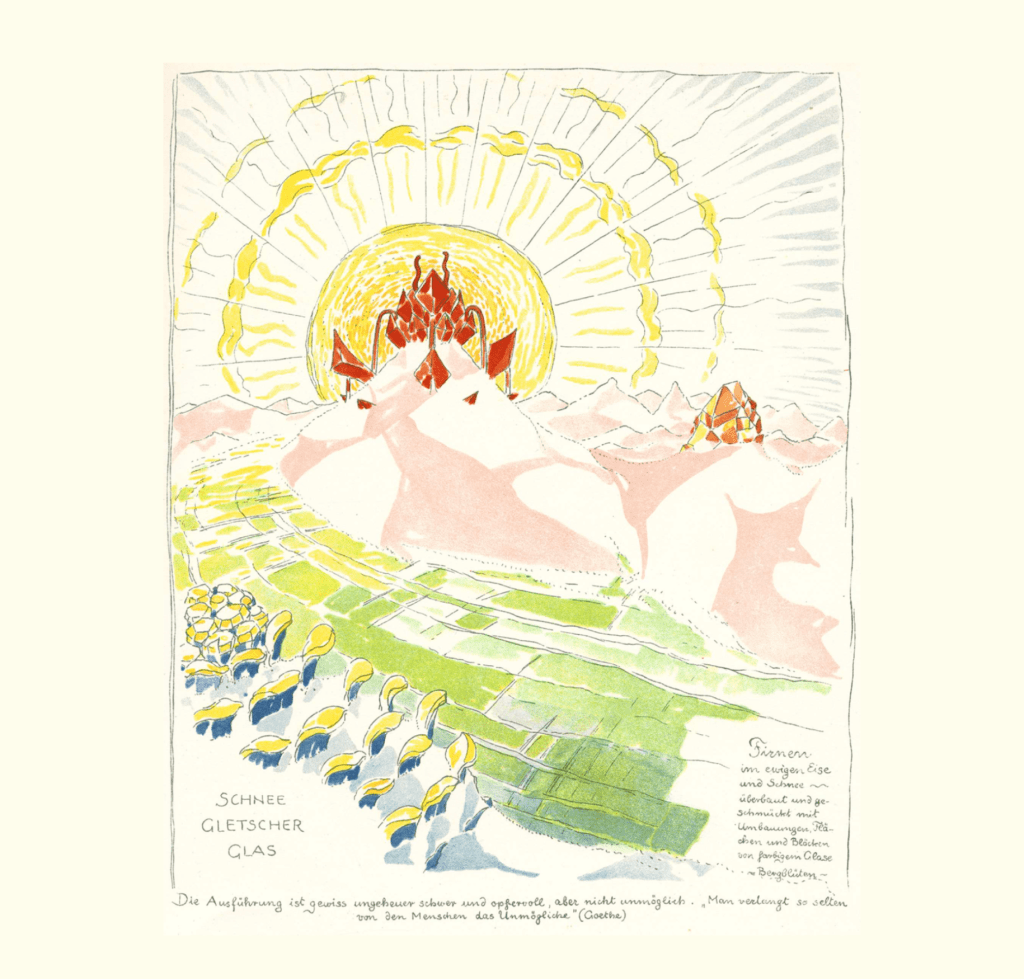

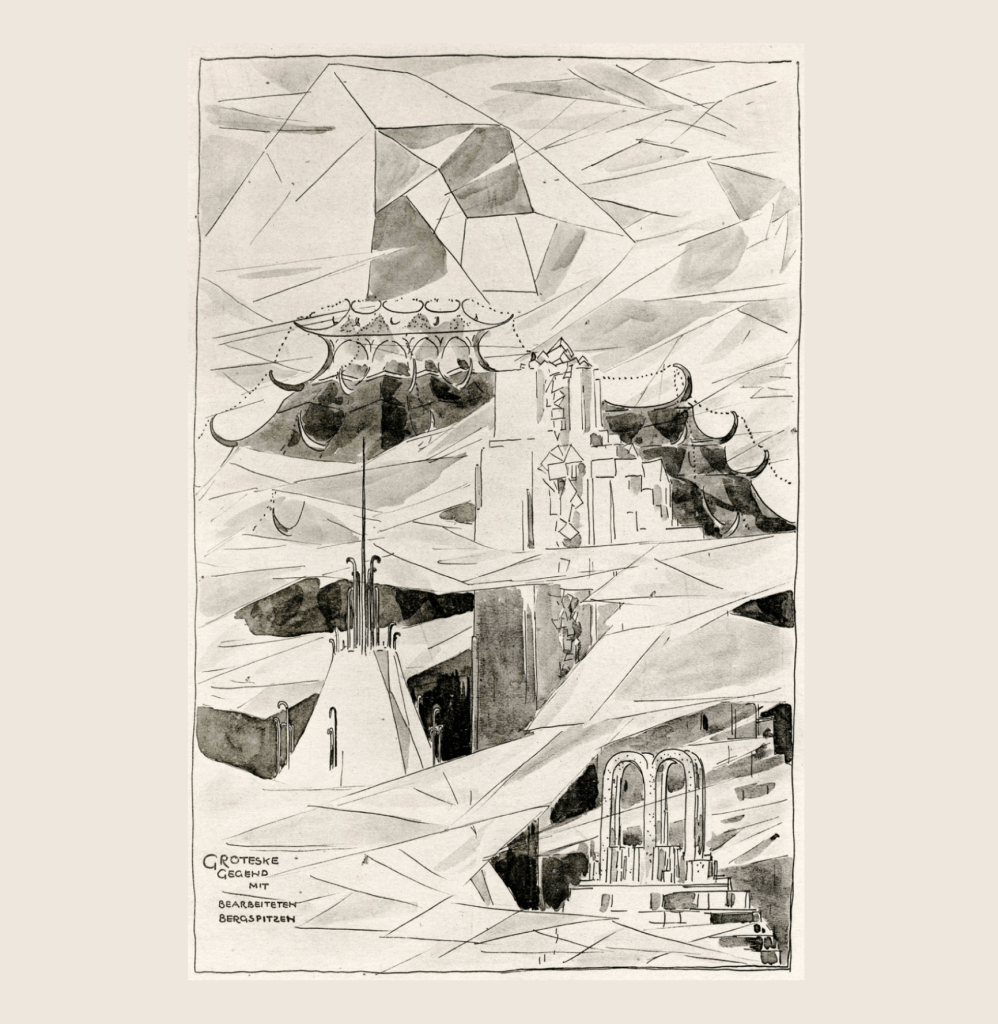

ʻThe Gray Cloth with Ten Percent White: A Ladiesʼ Novelʼ [Das graue Tuch und zehn Prozent Weiß: Ein Damenroman] (1914) is an avant-garde novel written by the German poet and architectural theorist, Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915), who was named the very ʻfirst Expressionistʼ in Herwarth Waldenʼs avant-garde art and literary journal ʻDer Sturmʼ of 1915.1 Scheerbart, who throughout his literary career strove to integrate his spiritual and romantic leanings with the modern world, left a posthumous legacy that would make him reconfigured into the spiritual ʻglasspapaʼ of the ʻGlass Chainʼ [Gläserne Kette] (1919-1921), a working group of German Expressionist architects that by means of letters with signed glass-related aliases, envisioned and shared amongst themselves anarchist utopias of crystalline architecture: pacifist asylums from the totalitarian regimes that had led to the mass destruction of the First World War. In the face of a rising secularism and disbelief in any form of governmental rule, which had proven to be self-destructive, glass ‒ with its mystical root in alchemy ‒ turned a metaphor for spiritual transcendence, not just of the individual but for the whole of a civilization; intending to lift man to a higher mode of sensory experience and political independence.2 This paper poses Scheerbartʼs novel at the heart of the glass-visions that marked the rise of early twentieth-century Expressionist architecture. Moreso, the leading figure of the Glass Chain, Bruno Taut (1880-1938), referred to his dear friend as ʻthe architectʼ3 of his famed ʻAlpine Architectureʼ [Alpine Architektur] of 1919 ‒ an architectural reworking of the Alps in which mountain tops merge with glass superstructures: a vision which comes to a climax when the structures even leave the earthʼs crust and extend towards the stars [sternbau]. As an attempt to visualize Scheerbartʼs narrative, several of Tautʼs prints assist the text. Finally, the aim of the essay is to determine the themes central to Scheerbartʼs romantic fantasy that would later become fundamental to a newly born movement of Expressionist architecture.

The Faustian Bargain

As in most of Scheerbartʼs science fiction stories, The Gray Cloth has a hero-architect of glass buildings, Edgar Krug, at center stage. Populating the planet with colored glass architecture, the protagonist finds himself in the thick of a science fiction tale set forty years into the future, circumnavigating the globe by airship with his future-wife, Clara. Enjoying all the goods that come from modern consumerism and air travel, Edgar marries Clara under the condition that she permanently wears a gray cloth with ten percent white, which she agrees to. The ten percent formula can be seen as a metonym that alludes to the mathematical efficiency associated with modern functionalism.4 The subtitle of the book, ʻA Ladiesʼ novelʼ further accentuates the readerʼs relationship with the main woman figure, Clara. It is as Scheerbart fictionalizes himself in the shoes of the ʻstarchitectʼ and pleas the reader to commit to his utopia of glass architecture. By subordinating her own appearance to the greater good of the colorful, glass buildings, Mrs. Krug has, as it were, ʻsoldʼ her ʻsoulʼ in order to commit to a higher, ʻspiritualʼ ideal. The idea of a Faustian bargain5 is therefore elegantly fused into the relationship between both Mr. and Mrs. Krug, as for the one constructed between Scheerbart and the reader himself. Hence, we could say that the protagonist, Mr. Krug, actually symbolizes Mephistopheles6, the devilʼs right-hand man, to which she ‒ the Faustian figure – sells her soul. It is actually this paradoxical nature of the modern man in Mr. Krug, being both protagonist and antagonist at the same time, which reflects Scheerbartʼs doubtful stance towards the modern world; for he is advocate, yet fearful of the ageʼs technological advancements. While it enables the potential of realizing his glass superstructures, advanced technology is simultaneously the central target of his satire; an ambiguity which is present throughout the novel.7

The Gesamtkunstwerk

Though, the Faustian Bargain also highlights a ‒ yet ironical – debate over the manner in which architecture and fashion correspond, which sets in motion questions that underline the modern-day Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), which is one the novelʼs central motifs.8 Through the eyes of the protagonist- architect, Scheerbart observes and reflects upon a world wherein colored-glass architecture creates an aesthetic synthesis of the things it encompasses. The atmospheric effects of light being filtered by glass binds objects together, spiritually. It becomes a force that reverberates into the tiniest details, making things shudder into a common movement, and so enables the potential of a total, integrative work of art. With light appearing as a perpetually changing dynamic, the protagonist constantly anticipates on accidental moments of euphoria. As a result, the novel becomes more of a staccato-paced sequence of short scenes with aphoristic phrases.9 An example of such is a scene when Edgar and Clara are about to get married in one of the formerʼs colored-glass buildings: “The Tower of Babel rose up like a cone such that each floor was a little smaller than the one below it. Then, suddenly, from the lower floors ascended silicate violin music. And it was the melody of a waltz. At the same moment, the light went out in the glass walls. And the lanterns came down from the ceiling and moved up and down, and then up and down to the beat of the music. This all looked very beautiful. And the whole Tower of Babel shouted with many voices, “Bravo”. And they clapped their hands.”10 The situation reaches a point where it is unclear if the building actually rises, moves, and shouts, or if the protagonistʼs euphoria blurs the boundary between realism and fantasy. However, by suggesting the otherwise static property of architecture to possess its own proprioception11, including human body parts, such as an ear, mouth and hands, the building is supposedly conscious of the situation. In doing so, the author places the spirituality of the occasion in the property of architecture, and thus matter. This is also shown in a scene where a table appears to be self-aware: “They laughed and spooned the tortoise soup. Edgar said: “Green growing swags hang over our dinner table. The table has also not experienced that before.””12 This merging of subject and object, experienced by the protagonist, is a consequence of the dynamics of light and color which render his environment into a sonorous whole. The perception of the protagonist is thus changed as a result of the integrative power of colored light.

Glass & Morphology

This merging effect reaches a point where things literally start taking on each otherʼs shape, and so the individualism of the object tends to get lost. In a feuilleton written sometime after the novel was published, the author Jessa Laam expanded upon this theme while simultaneously poking on Scheerbartʼs fiction: “I inspect my new house. The thing looks good. The dining room has glass everywhere. No cabinets. Everything between double glass walls, plates, glasses, silver. Buffet and credenza are missing; the whole room is a giant glass case. One press of an electric switch: the prismatic glass shines in beautiful colors. […] The narrator continues to inspect his house with a degree of awe until he suddenly finds himself in his music room, transformed into the famed Italian opera singer Enrico Caruso. The story becomes more fantastical as the narrator (now Caruso) stands in his glass shoes, singing notes determined by the changing colors of the glass to a crowd of female admirers.”13 In this excerpt, Laam places an ironic endgame to the merging of subject and object: modern man assumes a completely new form from the effects of colored light. The protagonist, when entering another space, physically transforms into an opera singer who sings in accordance with colored glass tones. Likewise, in Scheerbartʼs novel, color signals (similar to morse code) are used as a form of communication. This new method telecommunication expresses his search for a language that exists beyond the geographically bound, verbal forms of language as we know them; towards one that solely exists of form, light, color, and sound. This belief is also expressed by Taut in ʻThe Dissolution of Citiesʼ [Die Auflösung der Städte] of 1920, in which the author envisions peaceful agricultural communes placed in an anarchist setting ‒ a stateless society void of national borders.14 While in Scheerbartʼs novel the plot does not reach a state of actual physical transformation, Laam ironically expands on the theme: a further consequence of living in the properties of light and color. This, then, brings us to a difference between the earth-bound man of the past, and the Scheerbartian man of the future, who is transcended by light and air.

A body of Light and Air

As mentioned earlier, each physical object receives its quality from the manner in which it responds to a certain light hue. An example is the constant recurrence of animal figures in describing the effects of the glass architecture. Since glass is transparent and therefore treated as a non-material, it is polarized by the rich textures of animal skins, thus giving glass its definition by means of context. The buildings are also never described descriptively; thereʼs almost no clue of the architectural properties, only its effect on its immediate environment. Glass is thus a medium through which other things receive their meaning. One fine example that shows this function is the manner in which objects are constantly experienced through or in reflections of glass surfaces, or its natural counterpart: water. This is revealed in a scene when Mr. Krug and his friends find themselves at the peak of the Tower of Babel in Chicago and observe a landscape: “One saw the very colorful reflection of the palaces in Lake Michigan. Like hummingbirds, dragonflies, and butterflies the countless colors flickered along the moving waves of the lake. And the full moon glowed. It too was reflected in the water. Several airplanes traveled over the lake, letting their colorful floodlights frolic.”15 The scene shows how an object is valued through its resonance with the reflective state of water. In a similar way, history – or any preexisting cultural remnant – is portrayed through this lookingglass. In other words, by means of reflection one is able to experience such remnants, automatically placing ʻhistoryʼ in an elusive state, since its traces are never directly experienced. This distance towards history places the protagonist in a kind of aerial territory. He floats above the surface, above time-bound earthly matter. We could say that by means of glass architecture, which exists ideally in the qualities of light and air, and is therefore not ʻearth-boundʼ, the human being also gradually moves further away from this surface. The nomadic nature of the Scheerbartian man not only suggests a rising internationalism16, but makes him entirely disconnected from that which he originally belonged to: the earth. Interestingly, in Scheerbartʼs novel the point of perspective has also been displaced from the earthʼs surface and has moved up into the air ‒ whether it is from an airship, or a glass building on top of a mountain. The world is therefore reflected upon from another height, and architecture is designed and judged upon from birdʼs perspective: it has to look good from the airship! All these detachments from the earth show that the Scheerbartian man is one that exists in the zenith. He lives closer to the stars and the large gestures of the universe. Ironically, the protagonist even disgusts people living on earth and so instills a hierarchy between top and bottom culture, as shown in a discussion between Mr. Krug and a woman: ““It must, indeed, be really excruciating,” said one woman, “to travel over a large brick city.” “That,” replied Mr. Krug, “I never do. My air chauffeur zealously studies the maps in order to avoid all brick sites along the way. Therefore, my airship very often takes large detours so that I will not be reminded that people are still housed between bricks.””17

Proteus

By ironically framing an antithesis, Scheerbartʼs ideal, modern man could be seen as one that consists of the properties inherent to light and air ‒ something which is strengthened by motifs such as airships and aerial animals and insects. While it is obvious that the transformation idealized by Scheerbart is of a spiritual nature, Laamʼs transformed glass-house dweller, does bring to mind a mythological figure known as Proteus, an early prophetic and hybrid sea-God who occurs in the earliest legends as a subject of Poseidon, who can change shape of free will and in Homerʼs odyssey turns into a lion, a pig, water, a tree, a leopard, and a serpent within the space of seconds. The link between Proteus and the glass-house dweller is the analogy drawn between glass and water, which is a central motif in Scheerbartʼs novel: “Water,” he says, “really belongs, because of its reflection, to glass architecture.”18 Also, a similar hybrid creature comes to attention in the opening scene, where a group of people admires Japanese veil fish, of which their heads are those of lions, bulls, and human beings. Mr. Krug comments: “In this example one does not know if it is supposed to be a lionʼs head or a transformed human head. In any case, the beard and the eyebrows are also flowing fins.”19 This scene subtly hints at the merging effect of glass architecture, to which the protagonist himself is subjected. By questioning whether the head is of a lion or of a transformed human, it also harks back to Goetheʼs vertebral theory of skull organization, in which it is argued that either a progressive or regressive viewpoint can be taken in seeing the vertebrate skull as a transformation of the spinal vertebrae, or vice versa.20 The ties between Scheerbart and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) – who also compared the mythological figure of Proteus21 to the vital force that enables growth in natural phenomena – shows the formerʼs relationship with German Romanticism, who in a quest for a complete break with the past, paradoxically, longs for a spirituality that existed in antique times: their ability to create a synthesis of art and science. This longing is revealed when Mr. Krug suddenly speaks to his wife of his fascination with the recurrence of mystical numbers in archaeological finds: “The trinity probably also comes from the zodiac, the three points that do not lie in a degree allow themselves to be brought in a circular line. We continually find this very simple thing in the earliest ornamentation, we see the belief in the sky of the ancient priests. And that is why archaeology is so interesting. But I do not know whether you have understood very much of that.” Mr. Krugʼs fascination with past cultures and their astrological knowledge contradicts his constant attempt to break from history: he finds himself in between a longing for the old and the new, a struggle typical for a Romanticist. Mr. Krugʼs disbelief in his wifeʼs understanding of spiritual matters also underlines his lonesomeness, a burden which he consistently tries to, but never overcomes – Mrs. Krug has a terse character development, even though she eventually wants to wear the gray cloth herself. In the end, the latter asks Mr. Krug if he couldnʼt go back to archaeology, with him replying: “no”, “one who is seized by glass architecture lives in the glass colors.”22 This answer, finally, brings us back to the Faustian bargain, with Mr. Krug now being the subject of the trade. The change of roles, with his wife now formulating the question, places the protagonist in the role of the Faust-figure, instead of his wife, Clara. This shift in position between protagonist-antagonist and Faust-Mephistopheles once again marks the ambiguous psychological state of Mr. Krug, who has to live with the burden that comes from sacrifice.

Scheerbartʼs modern world is a kaleidoscope of colored light, a cosmic drama supposedly sublime enough to bring forth a metamorphosis of the collective soul, one that allows anarchism to function. It is, ideally, strong enough to eventually surpass any form of rule, for people are bound by the integrative power of light. With seagulls and airships flying along, and stars and lanterns of automobiles that flicker in rhythm, the world becomes a theatrical play in which nature and technology happily coexist. 23 With the novel set only forty years into the future – an obvious contradiction to the plotʼs technological advancements – Scheerbart suggests new beginnings: the world is a giant glass construction site and about to be drawn to the majesty of glass architecture – with Mr. Krug as its prophet. It is through short scenes that we receive bits of the effect glass architecture has on the experience of the protagonist, indicating a change in human perception which Scheerbart, prophetically, hints at. Those euphoric scenes, in which the world is described in terms of its effect, are what makes the novel ʻExpressionistʼ, for the sudden, sensory responses to glass-filtered light are ʻcatchedʼ by the author. The emotional effect, what the thing arouses, thus surpasses the ʻthingʼ as main focus, and it is exactly this reversal of roles which Taut was well aware of: “The head can at best have a regulating effect, she herself, her innermost being can only blossom from the heart, and this alone must speak.”24 The inability to access Scheerbartʼs fantasy with mere intellect makes it challenging to submerse oneself in his glass visions. Perhaps, after a period of time, when we pass a lotus-covered pond and have forgotten all about it, there appears a dragonfly, whose pink-colored wing flickers elegantly in the reflected sunlight. Maybe, with a flash of insight, we could take a little peek into this paradise of glass.

Featured Figure: Portrait of Paul Scheerbart. Photograph by Wilhelm Fechner, 1897. / Figures above are retrieved from: “Taut, Bruno. Alpine Architektur: In 5 Teilen und 30 Zeuchnungen. Hagen: Folkwang Verlag, 1919.” Watercolour and India ink. Fig.1: Teil 4. Kristallhaus. Fig.2: Teil 7. The Crystal Mountain. “Above the vegetation the rock is rough- hewn and smoothed into many crystalline shapes. The snowy summits in the background are crowned by glass-arch architecture. In the foreground pyramids of crystal needles. Over the ravine a trellis-like glass bridge.” 49.5 x 50 cm. Fig.3: Teil 9. Architektur der Berge. Fig.4: Teil 6. Architektur der Berge. Fig.5: Teil 10. Snow Glacier Glass. “Snowfields in the eternal ice and snow ‒ built up and decorated by superstructures. Surface and blocks of colored glass. Mountain blossoms. The execution is certainly very difficult but not impossible. ʻVery rarely is the impossible asked of menʼ (Goethe).” 46 x 41.5 cm. Fig.6: Teil 8. Architektur der Berge. Private Collection, Berlin.

Unpublished Work © 2023 Joseph Gardella

Endnotes

1 Herwarth Walden, “Paul Scheerbart,” Der Sturm, VI (Dec. 1915), p.96.

2 “[…] the glass-crystal metaphor had generally been expressed through more or less architectonic concepts. But with alchemy and later the Romantic and Symbolist movements, the imagery of transformation shed most of its architectural manifestation. It became a rudimentary pebble, an image of the soul or brain as this symbol became identified solely with the transformation of the self. The return in the early 20th century to the older, more architectonic, format in the works of Scheerbart, Taut, and a large number of other Expressionists signified a turning away from introspection toward a search for social identity and community.” Excerpt from: Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “The Interpretation of the Glass Dream-Expressionist Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 40, no. 1 (1981): p.20‒43.”

3 “[…] since he, who loves the nameless, declares the nameless to be a fundamental element in all works of architecture. And in his work, he is not the architect at all – the architect is our poet Paul Scheerbart, and even he is not, after all. It should shine the idea alone, unrestricted by human light.” Original text: “[…] da er, der an sich schon das Namenlose liebte, in allen Werken der Architektur das Namenlose für ein Grundelement erklärte. Und bei dieser Arbeit sei er gar nicht der Architekt – der Architekt sei unser Dichter Paul Scheerbart, und auch dieser sei es schließlich nicht. Es sollte in ihr die Idee allein, uneingeschränkt durch Menschliches leuchten.” Excerpt from: Manfred Speidel, “Bruno Taut, Retrospektive: Natur und Fantasie 1880- 1938” (Berlin: Ernst & Sohn, 1994), 165. Originally published in “Alpine Architektur” (Hagen: Folkwang Verlag, 1919).

4 John A. Stuart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.XXXV.

5 From the medieval legend of Faust, a Faustian bargain is a pact whereby a person trades his or her soul for greater knowledge or spiritual power, abandoning oneʼs moral principles in order to satisfy a desire.

6 Mephistopheles (or Mephisto) is a representative of Satan who claims Faustʼs soul, making the latter enslaved for eternity.

7 An example of Scheerbartʼs doubtful stance towards technological advancements is revealed in the novel when masked ʻair robbersʼ plunge Mr. Krugʼs glass museum on Malta. This scene refers to Scheerbartʼs prediction of military developments with the invention of air power, as dynamite torpedoes can be dropped anywhere one wishes. “The Development of Aerial Militarism and the Dissolution of the European Land Armies, Fortifications, and Navies” [Die Entwicklung des Luftmilitarismus und die Aufiosung der Europaischen Land-Heere, Festungen und Seeflotten] (1909), in: Rosemarie Haag Bletter, “Paul Scheerbartʼs Architectural Fantasies”, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 34, no. 2 (1975): p.83‒97. The negative consequences of the development of airpower, as expressed by Scheerbart, brings to mind a poem written by the Norwegian architect Sverre Fehn of 1988: ‘Is the mask living, has a doll life?’:

“The bullet made a dent in the surface of the earth, and the size of the hole was the same as the bullet. Today’s “bullet” has reached the invisible mystery, as it can destroy all life without rendering a mark on the surface of the earth. The spirit is now self-destructive. Matter has claimed a total victory. The mask is left behind in conversation with the doll.”

(Sverre Fehn & Per Olaf Fjeld, “Has A Doll Life?”, Perspecta, 1988, Vol. 24 (1988), p49).

8 A ʻGesamtkunstwerkʼ is a comprehensive work of art in which different art forms are bound into a conceptual whole. The term is often associated with the German opera composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883), who sought to synthesize poetic, visual, musical, and dramatic arts. The concept soon spread to the field of architecture and became a central theme in, for example, the Bauhaus art school (Walter Gropius, Paul Klee, et al.), as for a group of avant-garde, Viennese artists known as the Vienna Secession (Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann, et al.).

9 John A. Stuart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.XXXIV.

10 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.10-11.

11 Proprioception (or kinesthesia) is the awareness of oneʼs own body position, spatial orientation, and self-movement.

12 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.114.

13 Jessa Laam, “Erwachen im Glashaus. Ein Zukunststraum” [Awakening in a Glass House. A Dream of the Future], Berliner Tageblatt̶und Handels Zeitung, Saturday, 25.10.1913, p.6.

14 Thee ʻDissolution of Citiesʼ consists of urban settlements without centers, institutions, schools, marriage, and money. It is also a form of urban decentralization that can avoid dynamite war ‒ large cities would be prime targets for aerial bombs (a solution to the negative consequences of the developments of air power, which Scheerbart predicted). The essay is an ode to Scheerbartʼs visions. Bruno Taut, “Die Auflösung der Stadte” (Hagen: Folkswang Verlag, 1920)

15 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.7.

16 The rise of internationalism is constantly acknowledged when Mr. and Mrs. Krug travel around the world by airship. In most of the scenes they consume food that has no direct relationship with the place they are at. The country of origin is often mentioned with each consumption: subtly highlighting a distortion of food and place.

17 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.99.

18 Paul Scheerbart, Van Bergeijk, Herman. Glasarchitectuur. (Rotterdam: Nai010, 2005), 67.

19 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.5.

20 In the novel, an objectʼs individualism is lost as a result of the integrative power of everchanging colored light. The displayed artwork is a symbol of a growing nondual relationship between the objects that fall in the protagonistʼs perception. Goetheʼs theory is of relevance here, since his argument is that a skull and a spinal column are actually one and the same thing, and it depends on the viewpoint of the spectator in claiming which one comes first. It is exactly this ʻsubjectivityʼ which is centered in Scheerbartʼs novel. Goetheʼs argument: “[…] the skull as well as the spinal column as modifications of a primordial vertebrate”. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, (Brauning-Oktavio, 1956, pp. 4-144; Lenoir, 1987; Jardine, 2000, p.27-43). Similarly, in ʻMetamorphosis of Plantsʼ, Goethe argues that a plantʼs parts offer ready evidence of transitions, anticipating in their structure or coloration a subsequent stage. These processes could be read backwards as well. Thus we could, for example, see a sepal as contracted stem leaf, a stem leaf as expanded sepal; a stamen as a contracted petal, or a petal as an expanded stamen. Johan Wolfgang von Goethe “Metamorphosis of Plants”, introduction by Gordon Miller, (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2009), XIX.

21 “It came to me in a flash that in the organ of the plant which we are accustomed to call the leaf lies the true Proteus who can hide or reveal himself in all vegetal forms. From first to last, the plant is nothing but leaf, which is so inseparable from the future germ that one cannot think of one without the other.” (Rome, July 31, 1787). The leaf (Proteus) is by Goethe understood asa dynamic origin that undergoes the process of metamorphosis: from cotyledons, stem leaves, sepals, petals pistil, stamens, and so on. Johan Wolfgang von Goethe, “Italian Journey: 1786-1788,” English translation, (New York: Schocken, 1968).

22 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.117.

23 Paul Scheerbart, “The Gray Cloth: Paul Scheerbartʼs novel on glass architecture” (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2001), p.91, 98.

24 Bruno Taut, “Die Stadtkrone: mit beitragen von Paul Scheerbar, Erich Baron, Adolf Behne.” (Jena: verlegt bei Eugen Diederichs, 1919), 87.