City Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ (German: ʻDer Städtebau nach seinen Künstlerischen Grundsätzenʼ) is a treatise on city planning written by the Viennese architect and theoretician Camillo Sitte (1843-1903), first published in 1889. In the book, Sitte advocates for an artistic approach to city planning, a view which contrasted modern city planning, which according to him, had become a purely technical process. Based upon ideas derived from ancient Greek and Roman cities, as well as Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque cities, primarily Italian and German, the book sets forth a set of doctrines which an artistic urban square ought to follow: First, squares are places where the most important buildings are housed, together with fountains and statuary. Second, on such squares the middle should always be kept open. This means that fountains, statuary, and greenery should always be placed on the edges of the square (the dead corners of passing traffic). Moreover, Church buildings should never be built in the middle of the square. Instead, they ought to be placed on the edge as well, enclosed between other buildings (as is common in Italy). Thirdly, Sitte argues that the square itself should be an enclosed entity. This enclosure is necessary for it to establish a harmonious composition and provide man with a feeling of ʻinteriorityʼ. This is for example achieved when streets enter the square at different angles, making it impossible to have more than a single view out of the enclosing mass. Forth, since squares accentuate central buildings and vice versa, the width, depth, and height of a square and her main building(s) should always be proportional. Fifth, beautiful squares do not need strict mathematical symmetry but may be completely asymmetrical. Moreover, irregularities within squares often provoke interesting vistas. Lastly, as a rule square are not built alone but they exist in group relationships with other squares within a city.

The book also offers a critique on the urban development of Sitteʼs home city, Vienna, and the establishment of its Ringstrasse; which includes several examples of alternative urban arrangements that follow the artistic principles formulated in his treatise. These urban alterations will function as our case studies and are visualized/presented on site. Firstly, we will introduce the Ringstraße developments during the second half of the 19th century, and discuss how the urban environment reflected the socio- politcal situation Vienna found itself in. The context provided in this first part will function as a base to which Sitte formulated his critique. Secondly, we will analyse Sitteʼs plans made for the Ringstraße, and determine how he gave rise to a new psychological understanding of space. From here, we will turn to Sitteʼs ambition in reviving the role of the public square in a time when urban planning was marked so strongly by infrastructural purposes. We will analyse how his approach to city planning marked a return to the ancients ‒ which will be supported by a short analysis of Gottfried Semperʼs (1803-1897) Kaiserforum (1869) ‒ a remodelling of the emperorʼs court, the Hofburg. Finally, we will discuss the role of the public square in todayʼs day and age and so determine Sitteʼs relevance in a contemporary milieu. The case studies are chosen for they accurately reveal the conflict inherent in Viennaʼs growing urban environment at the end of the 19th century, its ambition to become a city of stature, and the estrangement of public space in the face of modern man.

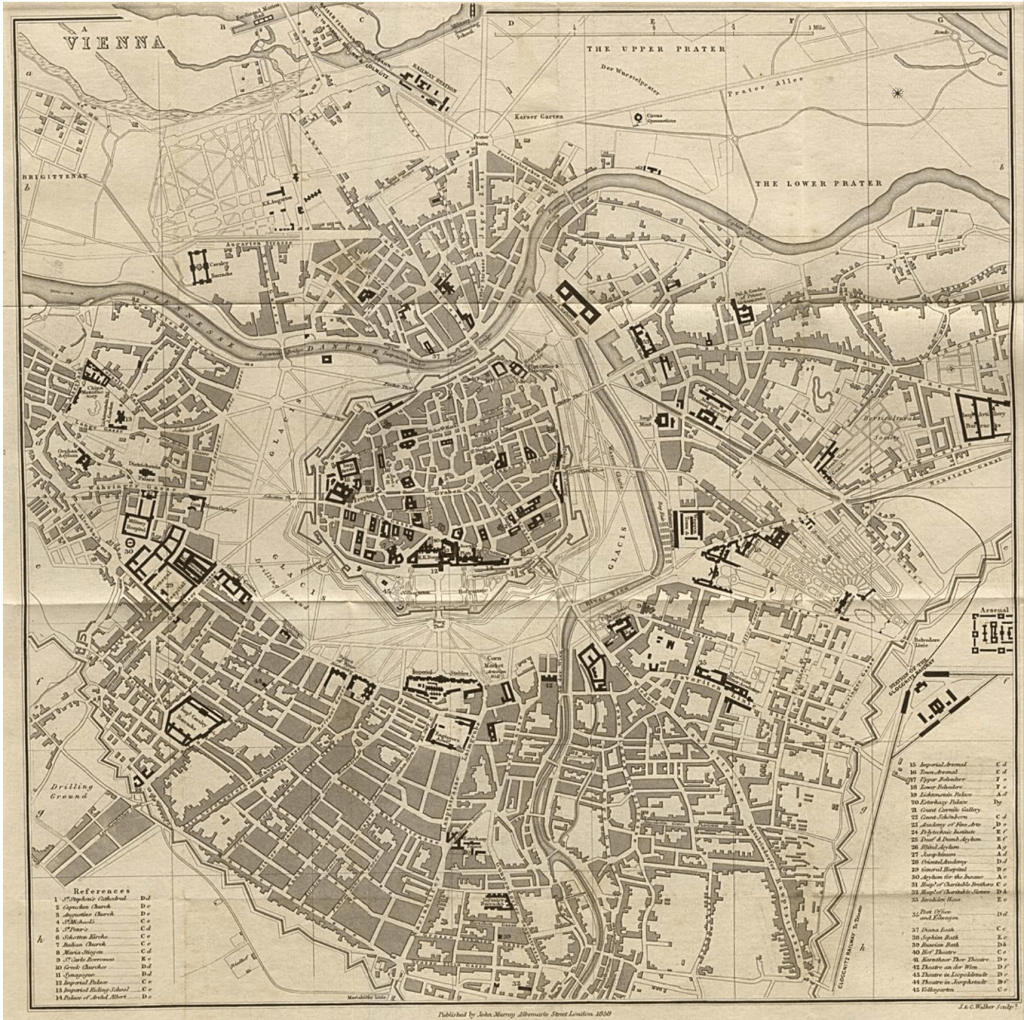

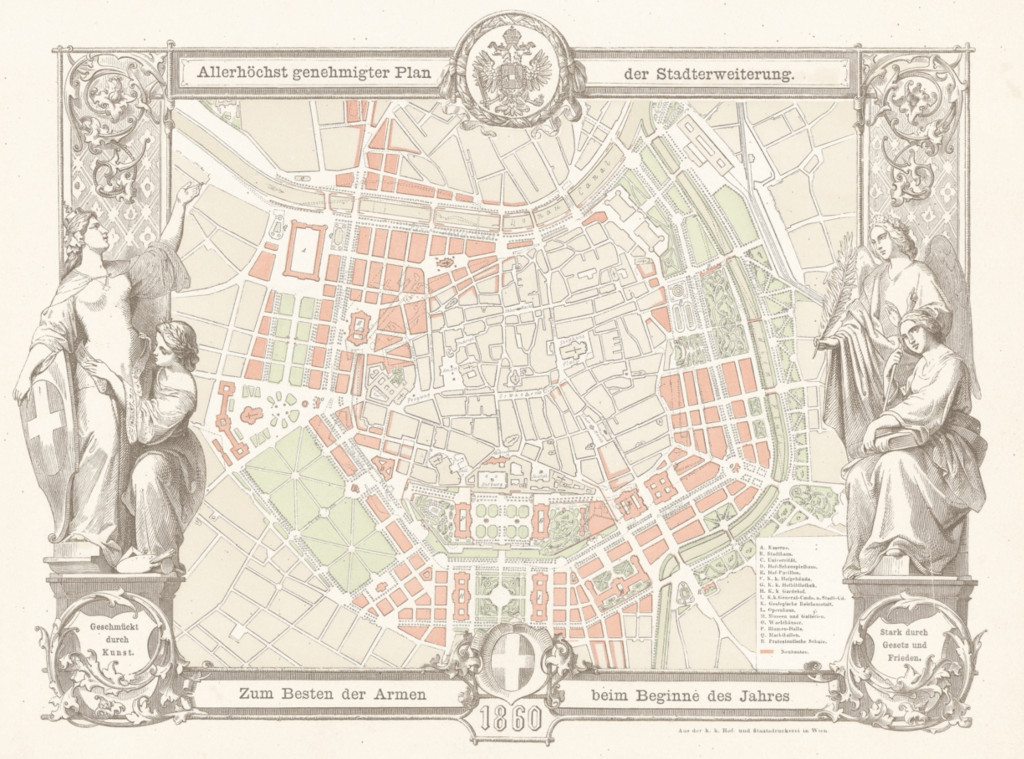

Figure 1: City Map of Vienna, published by John Murray, London 1858 / Figure 2: Design Proposal, Vienna Ringstraße. Ludwig Förster, 1860. Source: Hof und Staatsdruckeri Wien.

The Ringstraße: A Cultural Topography

The Ringstraße is a three-lined boulevard that encircles almost the entire Inner Town district of Vienna, being located on sites where medieval city fortifications once stood (Figure 1). In 1857, the emperor of the Austo-Hungarian Dual Monarchy Franz Joseph I (1830-1916) initiated the expansion of the inner city with due consideration to an appropriate link with the suburbs and the beautification of the Imperial Capital and palace of the Habsburg Dynasty: the Hofburg. While the initial plan focused on the celebration of monarchical, military, and sectarian power, drastic changes to Viennaʼs socio-political situation have directly affected the architectural and urban layout of the Ringstraße. Therefore, we can interpret it as a ʻcognitive mapʼ on which the historian sees that iconography that tells of both the transformation and the character of a newly emergent economic-social structure of Franz Josephʼs empire. 1

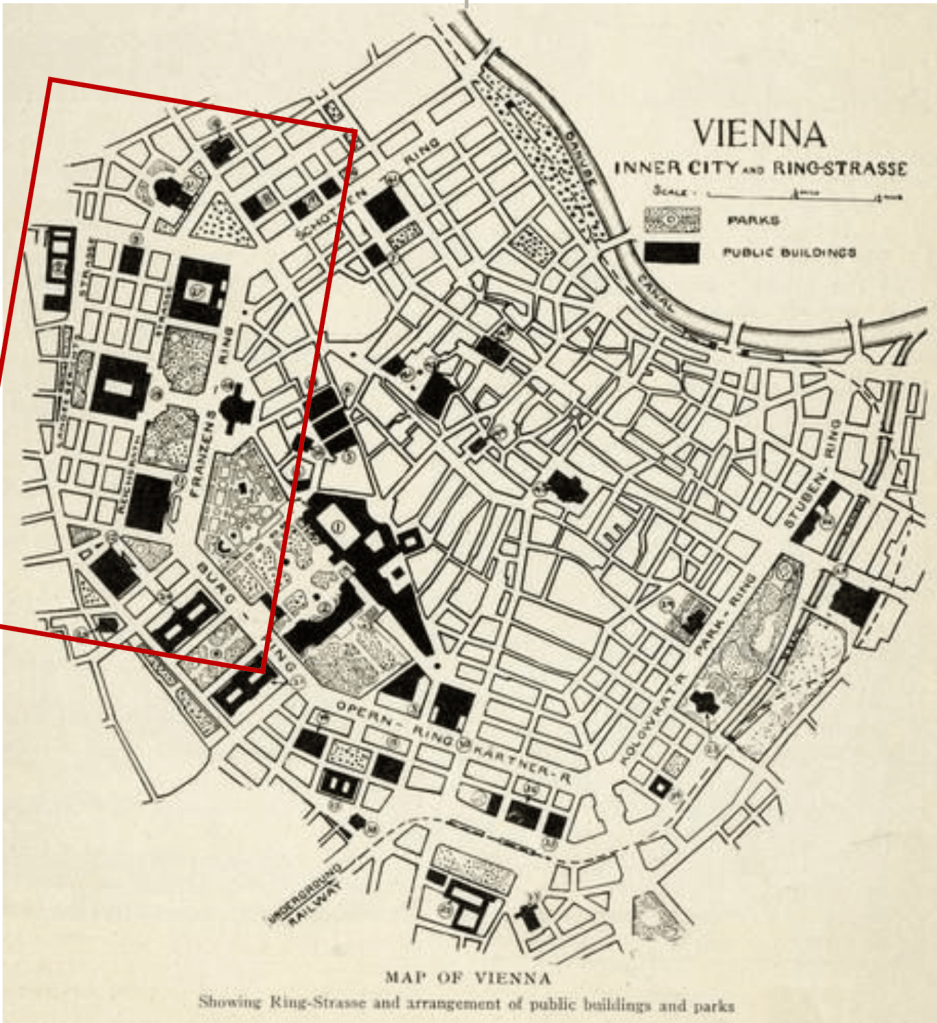

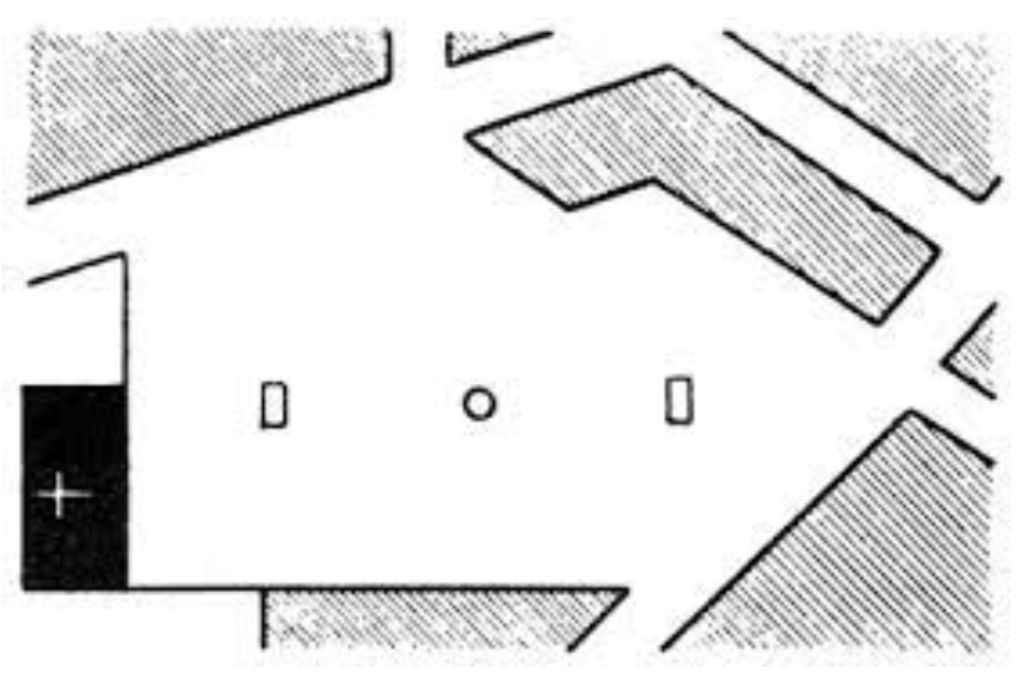

Figure 3: Vienna: Sitteʼs suggested transformation of the western portion of the Ringstraße. Camillo Sitte. City Planning According to Artistic Principles, 1889. p.157.

The Ringstraße: Liberalism and Decentralization

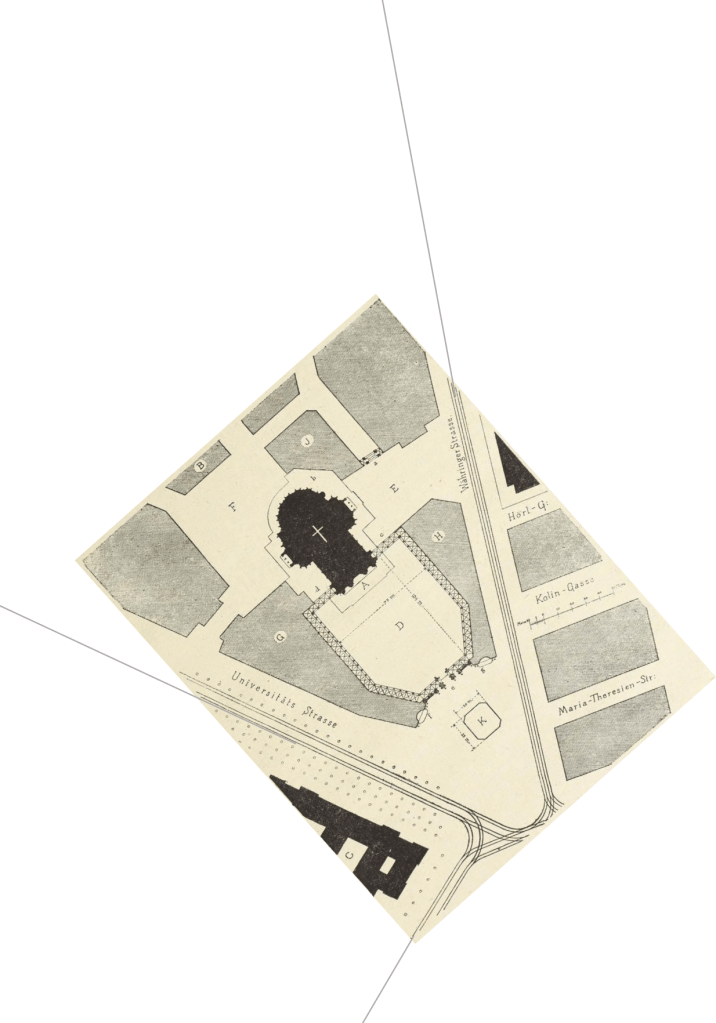

Following a military defeat in 1859 by Sardinia, there was a change in the political structuring of the Habsburg Dynasty, with the liberals of Austria seizing power in the western section of the empire ‒ of which Vienna became their political bastion. To hold the multinational state together, dynastic centralism was written off in favour of democratic capitalism. As a result of the ascent of Liberalism, all the material expressions that united the crown, the military and the church were strongly rejected; a change which clearly had its imprint on the built fabric of the Ringstraße. When Ludwig Förster (1797-1863) came up with his winning framework plan in 1860 (Figure 2), the ambiguity present in Viennaʼs socio- political situation becomes clear: the design doomed too imperio-centric for the liberals, with the Hofburg being the focal point of the plan. In response, the liberals called for an urban layout without a hierarchical order, thus rejecting all symbols of absolutism. As a result, the Ringstraße was planned without having any architectonic containment and visible destination; the avenue being the only form of coherence.

“The public buildings float unorganized in a spatial medium whose only stabilizing element is an artery of men in motion.”

C. Schorske (Fin-de-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture, 1980)

Figure 4: Map of Vienna, 1904, (with the western section accentuated). Plan retrieved from: scalar.usc.edu.

The Ringstraße: Sitteʼs Critique

The quotation by the historian Carl Schorske (1915- 2015) on the previous page gives us an accurate impression of the mentality behind the design of the Ringstraße, where dwelling in public space is subordinated to the idea of horizontal movement. It is exactly against this notion that Sitte formulated his critique. He argued that it was within this cold sea of traffic-dominated space, that islands of human community should be created. In other words, he wanted to arrest the aimless flow of human movement in pools of satisfying scale, and so re- create the experience of community within the framework of a rational, modern society. This lack of human scale and the fact that the public buildings are isolated in enormous empty spaces, would lead to people feeling dwarfed, resulting in a new modern- day neurosis: augoraphobia (the fear of large public spaces). In response to these issues, Sitte came up with an example of an urban arrangement for the Ringstraße, in which he integrated the principles articulated in his treatise. The overall design, which consists of several alterations, is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 5 (top): Votive Church with plaza, Vienna. Postcard from Vienna. Pre WWI. Source unknown. / Figure 7: Burgtheater, Vienna. Photograph taken around 1920. Source: Ullstein Bild – United Archives / Figure 8: Ringstrasse with Parliament, City Hall and Burgtheater. Postcard from Vienna. 1965. Source Unknown. / Figure 9: Plan Piazza Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy. In: City Planning According to Artistic Principles. Camillo Sitte, 1889.

The Plaza Effect

In the fifth chapter of ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ, Sitte makes numerous references to old irregular-shaped Italian piazzas that have grown over centuries and so have gradually generated strong artistic effects. In support of his critique on the perfectly laid-out symmetrical grid-system that characterizes modern city planning, he argues that an irregular-shaped piazza provides a greater variety of possible perspectives, while it also prevents the spectator from being able to immediately comprehend and rationalize its form: an example of such is the Piazza Santa Maria Novella in Florence, Italy (figure 9). Sitte claims that this piazza is often perceived as being 4-sided while it actually has a 5-sided shape. In other words, there is a discrepancy between the actual plan and the mental image formed by the spectator, which is a result of the fact that man is only able to see three sides of the plaza at once, with the others remaining unseen behind the back of the observer. When a plaza is designed two-dimensionally and excludes the in- situ experience of the spectator, and therefore the inexactitudes that come from optical limitations, such a space will not produce a discrepancy between the physical and mental image, and so might cease to stimulate the spectatorʼs imagination. If a discrepancy were to exist and the space turns into a puzzle for the eye, there emerges a picturesque quality which Sitte terms as the plaza effect; appearing only when physical reality and the mental image are out of sync. In his attempt to make city planning an artistic endeavour, it is exactly this spatial effect which Sitte believes the city planner needs to deal with: to turn the citizen in an active participant by the stimulation of oneʼs imaginative capabilities.

Multi-perspectivity

Apart from optical discrepancies, another feature which Sitte values is the richness in perspective views. In the fifth chapter of his treatise, Sitte discusses the relationship between monumental buildings and their adjacent plazas. In antique and medieval times, a plaza was composed in such a manner that each of the major buildings, like the one accentuated in the plan of the Piazza Santa Maria Novella, is experienced from a great variety of perspectives. The buildings discussed in the chapter are irregularly placed, approached orthogonally, and embedded within the built fabric. The disposition between the building in focus and the adjacent plaza, as for the fact that there are often several dissimilar plazas grouped around them, allows the spectator to have a constantly changing experience of the building in focus. The grouping of plazas around a palace or church – which is a frequent phenomenon in Italy ‒ gives each noteworthy façade its own plaza, and so constantly changes the spectatorʼs visual frame of reference when moving through the urban fabric. On the other hand, the modern-day method of placing monumental buildings in the very geometrical centre of the plaza and to engulf them in a sea of open space is a deed which, according to Sitte, not only reduces its size in the eye of the spectator, but also destroys any diversity of effect (there only being a maximum of three possible different perspectives). The monument should not be seen in its entirety but ʻstagedʼ in such a manner that it reveals itself in a fragmentary fashion. In doing so, the spectator is required to use his imagination in constructing an image of the entire edifice. An example of an urban plan designed by Sitte in which this approach is reflected is the constellation of plazas that surround the Votive Church, located along the Ringstraße.

Figure 10: Vienna: Sitteʼs project for the transformation of the Votive Church Plazas. Camillo Sitte. City Planning According to Artistic Principles, 1889. p.144.

Case (1): Votive Church Plazas (1889)

In all three of the plans made by Sitte for the Ringstraße, the intention was not only to disrupt the continuous line of movement that characterizes the street, but also to provide each of the public buildings ‒ which Sitte was so fond of ‒ its righteous plaza(s) and thus to allow each façade to have its ʻaudienceʼ. The first case study, and also the most extensive one, is a design of three plazas that surround the Votive Church (Heinrich von Ferstel, 1879). The fact that the building is completely isolated by open space (figure 5), allowed Sitte to design a group of plazas and so give each façade its own character. The first plaza communicates with the front façade and is completely enclosed by an arcade. The number of square meters covered by the plaza is actually three times the amount of the front façade, an amount which cannot be exceeded according to Sitte, or it would lose its proportionate relationship. While the interior of the plaza would stylistically correspond with the cathedral (the arcade having pointed arches), the outside of the two adjacent building blocks would be designed in a High Renaissance style, and so harmonize externally with Von Ferstelʼs (1828-1883) university building. Style is thus used as a form of communication on a scale that exceeds the architectural domain; it is utilized to harmonize that which is within oneʼs optical range. In his treatise, Sitte explains this principle in the following manner: “whatever the eye can encompass at once should be harmonious and that which one cannot see is of no concern”.6 The other two plazas, which are optically excluded from the first one, are respectively located along the side- façade and the back of the cathedral. The former is designed as a deep plaza and responds to the long and narrow form of the transept, while the latter communicates with the circular form of the ambulatory and its sculptural flying buttresses. Each noteworthy façade thus has its own, authentic plaza from which the cathedral can be admired.

Figure 11: Vienna: Sitteʼs project for the transformation of the Rathaus plaza. Camillo Sitte. City Planning According to Artistic Principles, 1889. p.150.

Case (2): Rathaus Plaza (1889)

The second project for the transformation of the Ringstaße is the urban arrangement in front of the Wiener Rathaus (Friedrich von Schmidt, 1883) and the Burgtheater (Gottfried Semper & Karl von Hasenauer, 1888). In contrast to the Votive Church, which was surrounded entirely by open space, only the façades that face the Ringßtrasse could be remodelled. The enormous space situated between both monumental buildings (figure 6) is broken in two by a large U-shaped building block. In doing so, the wide front façade of the Rathaus obtains a corresponding ʻbroadʼ plaza. Here, thereʼs also an arcade running around and enclosing the space, with only a central gate interrupting it to create a vista from the Burgtheater to the townhallʼs central tower. The U-shaped building block, which have one or two less floors than Ringʼs usual apartment blockʼs height, are topped with four small towers that correspond with the oneʼs on the Rathaus. On the other side of this plaza there would normally be the main traffic artery, however, in Sitteʼs design, it is displaced along the front of the townhall and so there arises an open space at the back of the theatre. To balance the convex shape of the central volume Sitte designed a concave counter movement edged by two monuments. While the building has several corners that already indicate part of a plaza, the proximity of the adjacent building blocks makes it impossible to create a plaza grouping around it. Only at one corner (j), a colonnade extends out of the building line and forms a small plaza.

Figure 12: Vienna: Sotteʼs projected plaza layout in front of the parliament building. Camillo Sitte. City Planning According to Artistic Principles, 1889. p.155.

Case (3): Plaza in front of the Parliament Building (1889)

The third and final alteration of the Ringstraße is the plaza in front of the parliament building (Theophil Hansen, 1883). Since Sitte has relocated the infrastructure to the back, a public square could be arranged in between the building and the Volksgarten. He claims that the Viennese people are yet to see this building in the right manner, and like all the architectural ʻbeautiesʼ along the same street, it presents itself as an ʻexpensive wallpaperʼ glued to the face of the wall.7Like the convex- shaped façade of the Burgtheater, thereʼs no spatial development of the ramp in front of the parliament building. This Baroque motif is, according to Sitte, designed for a large-scale perspective, but does not even have its own forecourt. In front of the Volksgarten, a barrier is designed which balances the concave shape of the ramp and so encloses the plaza. On both sides of this element, there are open portals to the garden and so imply a connection with the inner city. The remaining edges are articulated as colonnades of which two triumphal arches direct one into the plaza.

A Return to the Ancients

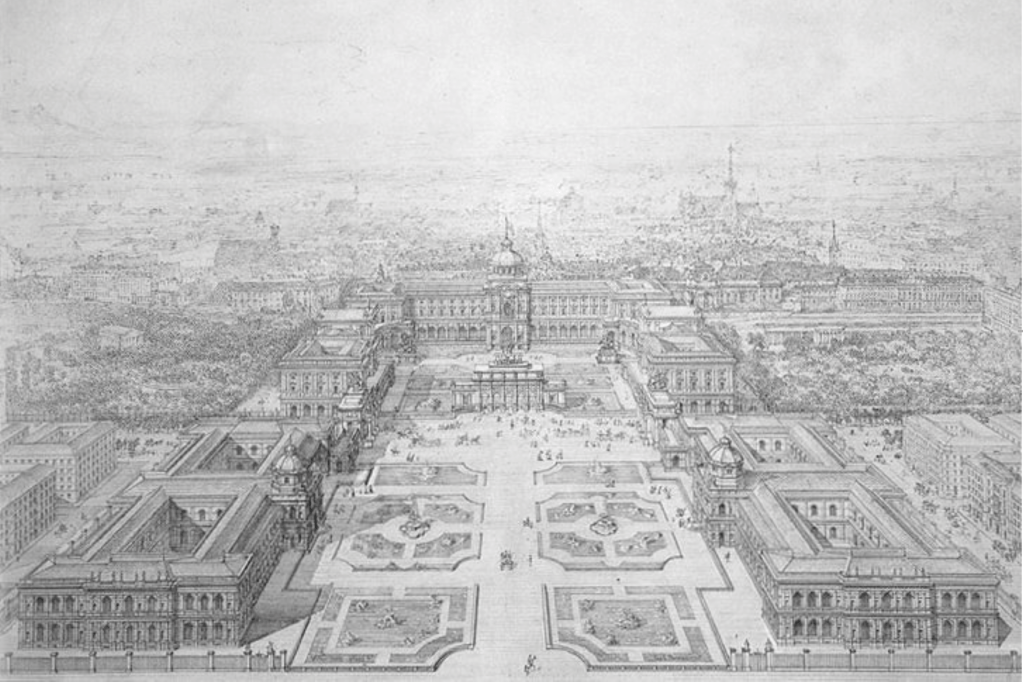

Since Sitte treats monumental façades as if they were a stage-sets in a theatre hall, they serve a double purpose: the façades both contain an architectonic space within, while also being part of an enclosure that exists on the outside of the building, one that is in tune with the proportions of the primary façade. In other words, architectonic containment does not stop at the building parameter, but continues within the fabric of the urban domain. This way of thinking can be explained since Sitte himself was an architect by trait and so treated public spaces as interiors. By orienting streets in such a manner that they enter the square orthogonally and by making use of devices that do not break the wallʼs continuity ‒ such as archways ‒ a square obtains an enclosed character which, like a room, is the main requirement of its space. In taking this approach, Sitte clearly intended to revive the ancient Roman forum and its role in society. While in todayʼs day and age architectural motifs such as staircases and galleries strictly belong to the building domain, in ancient times these elements belonged to the public realm. Sitte wanted to return to the external use of interior architectural elements and so abolish the distinct separation between both domains. An example of a public square that drew its inspiration from imperial Rome was the Kaiserforum designed by the German architect Gottfried Semper for the city of Vienna. While it is often thought that Sitte was only interested in picturesque town designs and favoured medieval irregularities over Baroque grandeur, his praise for the design of a new forum that connected the Hofburg with the Imperial Museums tells us otherwise.

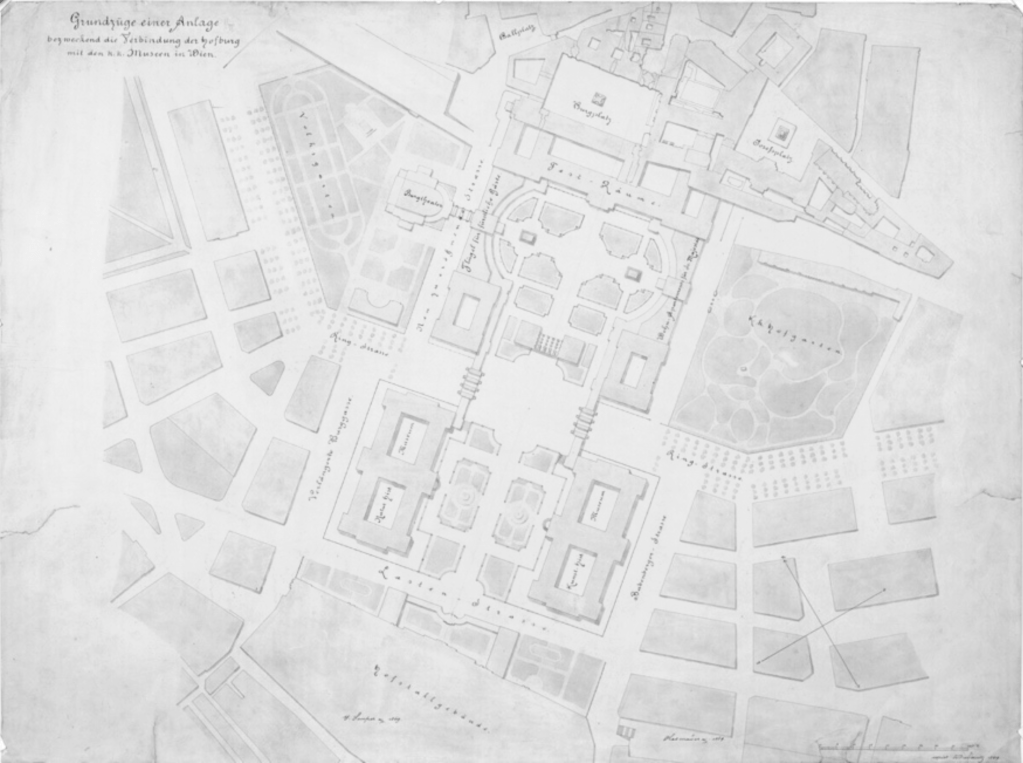

Figure 13: Hofburg, Gesamtplan mit Kaiserforum. Gottfried Semper, Carl von Hasenauer. 1869. Size: 57.2×76.6cm. Albertina, Online. Source: Sammlungen / Figure 14: Sketch of the Kaiserforum. Gottfried Semper, 1870. Source: Stadtchronik Wien, Verlag Christian Brandstätter, p.317.

Case (Extra): Kaiserforum, Gottfried Semper (1869)

Semperʼs Kaiserforum, which would have connected the court with centres of high culture ‒ the old and the new ‒ and so construct a large urban podium where ancient royalty could merge with bourgeois art and science, was in line with Sitteʼs principle of treating public squares as closed entities. The plan was to be divided into three sections: one plaza in front of the imperial museums; an in-between plaza flanked by two triumphal arches; and the climactic endpoint of the composition, where two exedras direct oneʼs vision towards the crown room. Even though Semperʼs Baroque masterplan would have created a necessary unity the Ringstraße lacked, the plan was obviously too imperio-centric for the liberals; being in strong contrast with the non- hierarchical order they desired. The rise and fall of Semperʼs Kaiserforum thus show us the ambiguous state Vienna found itself in during the second half of the 19th century; simultaneously desiring and rejecting a unity between imperial rule and high culture. It is exactly this ambiguity which is still seen today.

Discussion: The Plaza, what now?

Semperʼs Kaiserforum inclined a return to imperial Rome and revive the forum as a locus of community. Though, the fact that it never reached completion, tells us something about the role of the plaza in modern society. As expressed by Sitte in his treatise, the plaza has lost its function: urban motifs have left public space and are now withdrawn into the private space possessed by architecture; works of art are ʻcagedʼ in museums; folk festivals, parades and processions in open places have disappeared; operas take place in theater halls; fountains only serve an ornamental role; and daily topics are discussed in newspapers and commercial structures, not on the square. While Sitte was aware of this decline, we may ask ourselves, how has the role of public space shifted up until today? The rise of electronic media has created a new kind of forum; one that exists in a digital sphere and is not limited by physicality. Multi-dimensional this space is, yet unenclosed and repetitive. Maybe the work of Sitteʼs contemporary, Franz Kafka (1883-1924) fits with this question. In the latterʼs literary work, bureaucratic systems provoke a disengagement with the protagonist, the inability to find oneʼs own place within it and so become an ʻoutsiderʼ to oneʼs own environment; systems in which nothings is actually yours. We can argue that in todayʼs world, where interactions take place in a meta-sphere, this disengagement is even more strongly present. The little treatise written by Sitte and the end of the nineteenth century might be our bible for a return to the basics, to man-to-man communication, a feeling of being enclosed, and most importantly: to be an insider to the world.

Notes

1 G. V. Strong, ʻThe Vienna Ringstrasse as Iconography: socio-political history and baukunst during the era of Franz Joseph J of Austriaʼ, (History of European Ideas, Vol. 7, No. 4,377-388, 1986), 378.

2 The map of Vienna is rotated counterclockwise so that the Hofburg becomes the designʼs focal point. Although the largest space planned for the Ringstraße was earmarked for the military (including protective parade grounds), it is ‒ quite contradictory – not allegorically represented in Försterʼs plan. Instead, the figures represent liberal culture (art and law); thus, the plan reflected the two competing forces that were active in Viennaʼs political environ during the second half of the 19th century: absolutism and liberalism.

3 Carl E. Schorske, ʻFin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Cultureʼ, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1979), 64.

4 Camillo Sitte, ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ, (London: Phaidon Press Ltd.,1965), 49.

5 In the sixth chapter of ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ this phenomenon is discusses.

6 Camillo Sitte, ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ, 149. / ʻStyleʼ, as a tool to harmonize architectural form, has, in Sitteʼs approach, moved away from the buildingʼs singular form and is used to aestheticize the urbaniteʼs optical frame of reference. This change ‒ from an exterior motif to that which is internally perceived – clearly positions Sitte within the Viennese environment that, during the end of the nineteenth century, was marked by a rise of psychological discoveries.

7 Camillo Sitte, ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ, 154.

8 Camillo Sitte, ʻCity Planning According to Artistic Principlesʼ, 32.

Bibliography

Sitte, Camillo. City Planning According to Artistic Principles. London: Phaidon Press Ltd.,1965. Collins, George. Collins, Christiane. Camillo Sitte: The Birth of Modern City Planning. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1986.

Sitte, Camillo. De stedebouw volgens zijn artistieke grondbeginselen. (Vertaling Auke van der Woud). Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1991.

Schorske, Carl. Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1979. Johnston, William. The Austrian Mind: An Intellectual and Social History 1848-1938. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

Bohl, Charles. Lejeune, Jean-François. Sitte, Hegemann and the Metropolis: Modern Civic Art and International Exchanges. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Strong, G. V. The Vienna Ringstrasse as Iconography: socio-political history and baukunst during the era of Franz Joseph J of Austria. In: History of European Ideas, Vol. 7, No. 4, p.377-388, 1986. Winkler, Tanja. Viennaʼs Ringstrasse: A Spatial Manifestation of Sociopolitical Values. In: Journal of Planning History, 2021, Vol.20, p.269-286, 2020.

Koller, Manfred. The Decorative in Urban Vienna: Its Preservation. In: Studies in Conservation,

Vol. 58, No. 3, p.159-175, 2013.

Moravanszky, Akos. The Optical Construction of Urban Space: Hermann Maertens, Camillo Sitte and the Theories of Aesthetic Perception. In: The Journal of Architecture, 17:5, 655-666, 2012.

Mahfouz, Nisreen. Cities and Urbanism: The Art of Transitional Spaces. A Comparison of Camillo Sitteʼs Thoughts in City Planning According to Artistic Principles (1889) With todayʼs idea of Transitional and open spaces. Manchester School of Architecture, 2019.

Hnilica, Sonja. History or Fairytale? Camillo Sitteʼs Metaphor of the Urban Space as A Memory. Analogous Spaces. International Conference Ghent University, 2008.

Feuerstein, Marcia. Camillo Sitteʼs Artistic Principles and the Enacting Public. 84th Acsa Annual Meeting, Regional Papers, Temple University, 1996.

Sitte, Camillo. Das Wien der Zukunft. In: Der Bautechniker 11.1891, Nr.5, S.57ff.

Sitte, Camillo. Richard Wagner und die deutsche Kunst. Wien 1875.

Sitte, Camillo. Albert Kornhas „Das Zeichnen nach der Natur“. Freiburg i. Breisgau 1896.

Unpublished Work © 2022 Joseph Gardella