What do we envision when we think of a utopia? Do we imagine a world where the good surpasses the bad, eliminating violence, hunger, disorder and hatred, while preserving harmony and happiness? We might associate the latter with an environment wherein each individual can function according to his or her potential. Such a ‘system’, if we can call it that, is alive rather than dead; it expresses a state of flourishment and change rather than decay and destruction. This, then, clarifies an essential component that conceives utopia: it lives. The imaginative world on which this papers centres, envisioned by the Italian architect Antonio Sant’Elia (1888-1916), contradicts this story and is not our ideal utopia; on first glance it does not harmonize man with nature, nor does it seem to beautify or flourish the world around us. In his utopia, darkness seems to prevail light, into a world where there is no place for mankind. One could argue that this ‘fantasy’ was a projection of an inner conflict; an outlet of his very own struggles. However, what we will find out, is that this ‘struggle’ was not limited to him as an individual. The utopia he created, baptized as La Città Nuova (1914), was a reaction against a changing world of rapid industrialization. The architecture of his day clinched to the past; disguised the new world rather than confronted it. In the eyes of Sant’Elia, the built environment had to reflect and embrace the spirit of the modern man and the individual should therefore seek conflict with the weight of a new rising construct: the metropolis. His utopia expressed this weight. This paper therefore aims to determine how the Città Nuova answers this change in spirit.

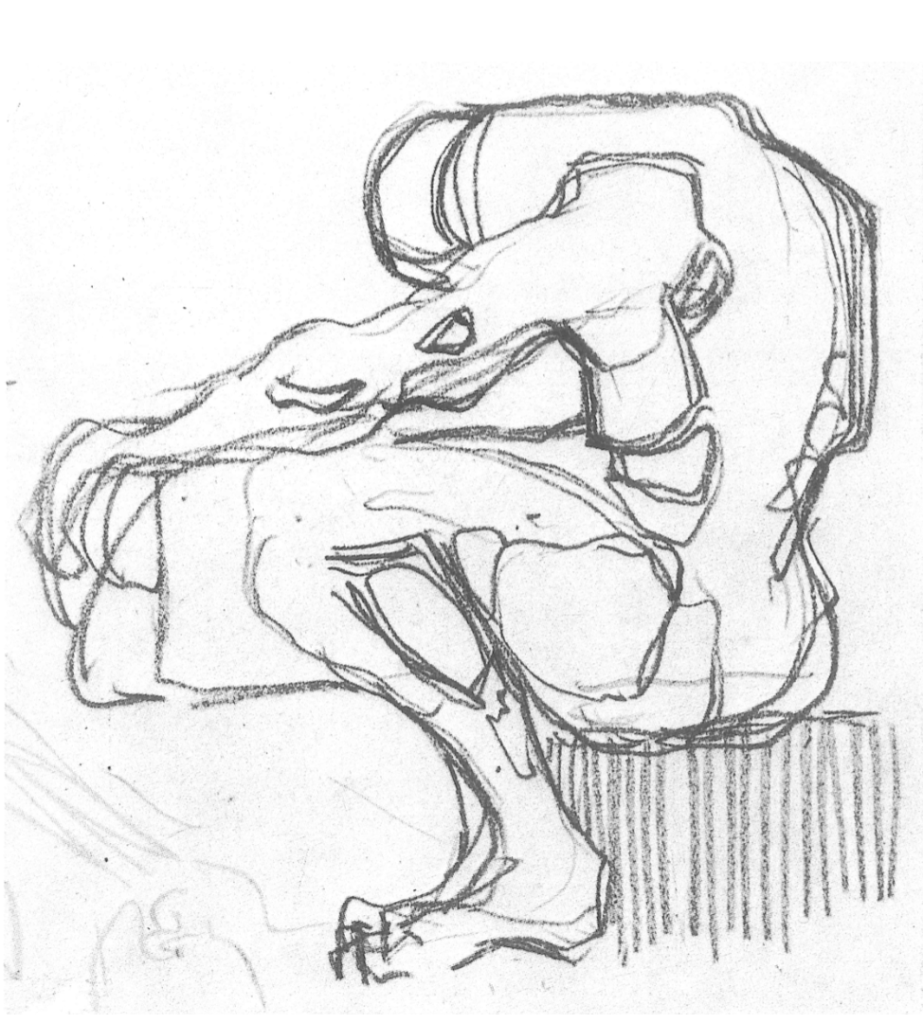

Sant’Elia’s early years as an architect, that is to say between his graduation and him joining the Futurist Movement, are explicitly characterized by a dark and melancholic mysticism which is seen in the grotesque imagery he drew during this period (Figure 1, 2).1 The first chapter discusses this characteristic by positioning Sant’Elia within his immediate environment, in order to understand how it functioned as a base for the drastic changes that he would eventually make. The second chapter makes a bridge from his early figurative work to sudden implementation of abstract forms. By making this connection, we will argue how his later work is actually a continuation of underlying grotesque forces, rather than being a break with his past. The third chapter continues to discuss this change by introducing how the grotesque found its shape in a new modern reality of abstract means. This direction is subsequently connected to the metropolis, becoming a new platform through which Sant’Elia could express the grotesque within a contemporary construct. The fourth chapter centralizes the metropolis by explaining the position of the human being within this system, while it simultaneously introduces Sant’Elia’s metropolitan utopia: La Città Nuova. The following chapters each deal with a particular aspect of Sant’Elia’s design; explaining how the grotesque forces were translated into an urban dimension. The purpose of this paper is thus to draw a continuous line throughout Sant’Elia’s oeuvre; examining how his search for pain, fear and conflict unfold and find expression in the several phases of his life, to eventually finding its climax in the Città Nuova. This determination is formulated in a research question, which reads as follows: “How is the ‘grotesque’ integrated into Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova and what does its presence tell us about the position of the human being within the modern metropolis?”

Figure 1 & 2: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1912. Decorative sketch with seated male figure. Decorative sketch with squatting figure. Black pencil on paper. 11.2×9.2cm&9.8×4.8 cm. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.123.

Early Work and the Grotesque

Antonio Sant’Elia left his birthplace Como in 1906 in order to establish a future in the at that time cultural and financial hub of Italy: Milan. The enormous increase of industry in Italy’s northern stronghold, resulted in the Milanese population being almost tripled in size over a mere thirty-year timespan; subsequently leading to the city’s worst housing crisis in its history.2 As for many fast-growing cities, the unhealthy and inhumane living conditions altered a new dimension within the arts: a reflection of the everyday. The negative effects industrialization had on the inner psych were to be expressed rather than be kept to oneself. Milan’s art scene was therefore, during the start of the century, possessed by a colony of symbolist artists who sought to express these negative mental states through physiognomy: portraying a person’s inner state through one’s outer appearance. The work of the symbolist artist Romolo Romani (1884- 1916), whom was a close friend of Sant’Elia and who also joined the Futurist Movement, clearly exemplifies this new direction (Figure 3): figuration and abstraction melt into each other to create a dark and almost frightening effect, which is strengthened by an obscure silhouette indicating the presence of a devil-like figure. The thematization of the metropolis is also literally figured in paintings produced during this period, which is for example seen in La metropoli del future (Figure 4) by Domingo Motta (1872-1962). Here, the metropolis is portrayed within a constant luminous and chromatic radiation. This ‘energy’ encapsulates and suppresses a group of figures that appear to be strangely alienated human being. The eyes of the figures are completely darkened, indicating a demonic presence or void that seems to be the result of this ‘metropolitan’ radiance.

In both examples one can extract a sense of darkness buried within the psych of the human being. The growth of grotesque expressions, as a means of portraying negative psychic states, was not just bound by the visual arts but also by other creative traits: architecture, literature and theater. In the case of the latter, it was the founder of the Futurist Movement Filippo Marinetti (1876-1944) who created Italy’s first Symbolist theater journal named Poesia (1905). One of Martinetti’s plays introduced robotic characters that reflected the “deadening force in bourgeois existence”.3 This once again indicates the presence of a darkness rooted within daily urban life, which the Futurists aimed to express; provoking the audience to disorientation, shock and violence.4 The rise of grotesque art also went hand in hand with the developments of psychology during the turn of the century. Psychology, as a self-conscious field of experimental study, was only ‘discovered’ recently and made a big impact on grotesque art, which according to the art critic John Ruskin, is capable of producing a “spiritual response after a feeling of awe resulting of fear which made it higher than laughter and horror”.5 Grotesque thus altered a captivating melancholic effect which began to encompass many creative traits. In the case of architecture, such symbolism was introduced in Italy via the Art Nouveau, and more specifically through its Italian variant known as the Liberty. This style altered a prominent position in Italy’s architectural scene via the Turin Exposition of 1902; an event that saw the style becoming the first foreign avant-garde to make itself “felt in Italian soil”.6 The exposition showed the first symptoms of a clear break with Italian historicism: “Only original products that show a decisive tendency toward the aesthetic renewal of form will be admitted. Neither mere imitations of past styles nor industrial products not inspired by an artistic sense will be accepted.”7 The emphasis on ‘artistic renewal’ gave architects and artists the opportunity to distance themselves from historicism and reinterpret the iconographical layout of buildings. This led to a free expression of emotional states without having to confirm to historicist criteria. One of the typologies through which the Liberty could explore this new approach, as it gave them a great artistic freedom, was funerary architecture.8 Instead of the traditional religious imagery that often represented the Resurrection, architects could now freely express the actual emotional state associated with such architecture: death.

Figure 3: Romolo Romani, 1902-1911. Stati d’animo Umani.Unknown Dimensions. Retrieved, November 2020. Source: http://www.pittoriliguri.info / Figure 4: Domingo Motta, 1908. La metropoli del futuro.Unknown Dimensions. Retrieved, November 2020. Source: http://www.pittoriliguri.info

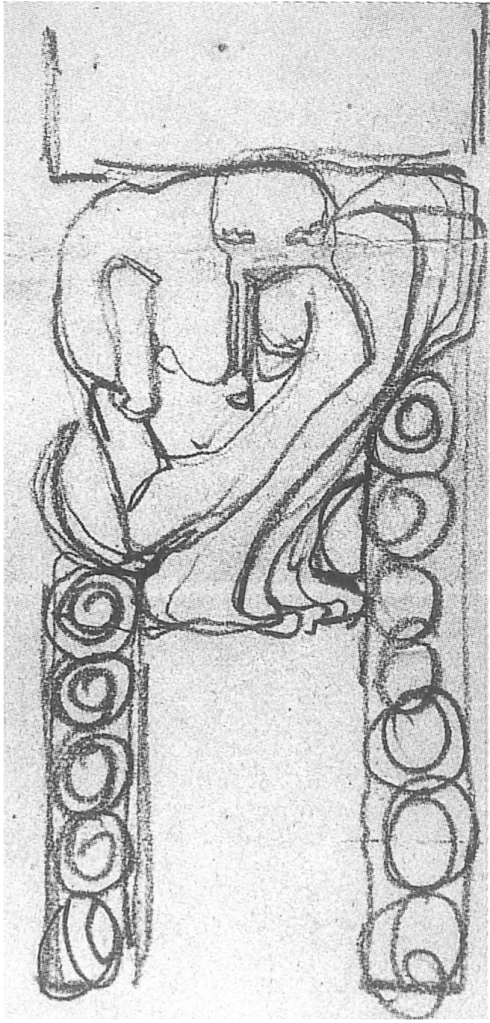

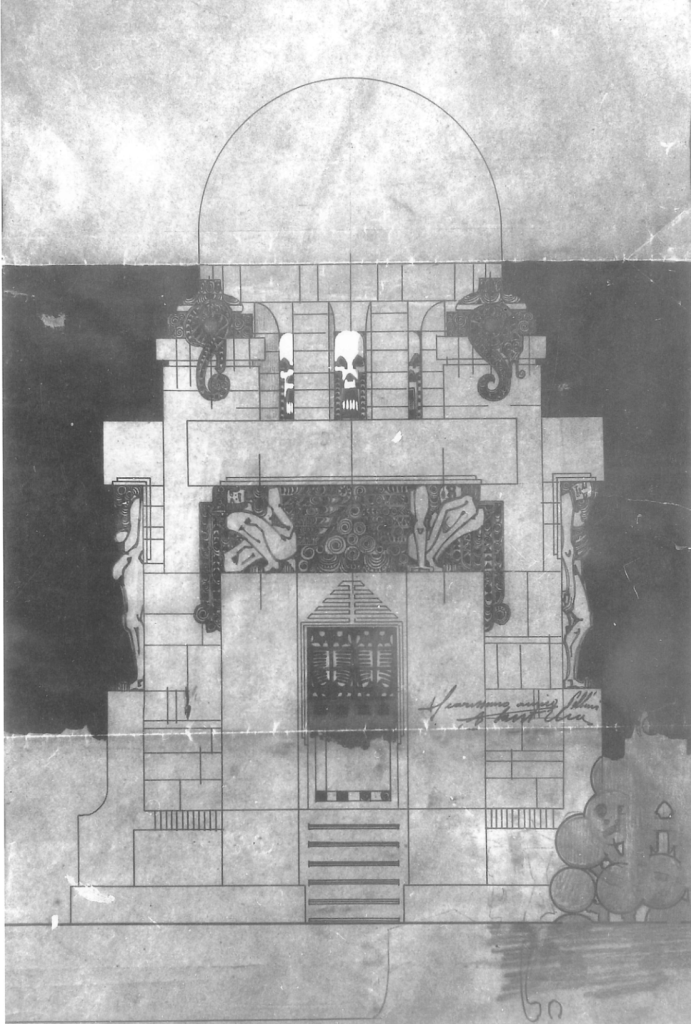

Antonio Sant’Elia found himself in the midst of this changing architectural scene and it affected his work exceptionally. The first displayed image (Figure 5) shows one of the first studies he made for a cemetery building. This tomb, which has clear Secessionist influences in terms of mass and structure, is decorated with grotesque imagery. The crumpled women figures have sagging bellies and breasts and are looking downwards. One of the figures is entangled by a black serpent, a feature which clearly makes reference to the Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt (1886-1918). In Klimt’s work woman figures and black serpents are often pictured together, symbolizing the realm of the underworld and the dead.9 The tomb thus clearly shows the symbolist root of Sant’Elia’s early work, a source of inspiration that would have a lasting impact on the rest of his life. Another example of funerary architecture is shown in the second image (Figure 6), which is the Monza cemetery designed by Sant’Elia and Italo Paternoster in 1912. The iconography, though being less dramatic than seen in the first example, still consists of “studied gestures of grief”: strangely mutated serpents with sphinxlike torso’s and wings are combined with skull motifs.10 However, it is the surrounding setting that primarily contributes to the overall dark and mystical effect of the design: a nocturnal background, swirling clouds, oddly shaped trees and an angry- looking set of figures in the foreground. The difference between the two examples is the shift in attention toward the overall ‘mood’ of the environment, by creating a scenographic and holistic image. While the first example solely focusses on the architectural representations, the second image starts to show a change toward an ‘atmospheric’ translation of the same dark melancholia that we find in his grotesque imagery. While this change is yet to influence the course of his architecture, it indicates how Sant’Elia became aware of the possibility to translate emotions through abstract means instead of subject matter. The figurative and the abstract, like in Romolo Romani’s work, start to fuse into each other and his drawing of the Monza cemetery therefore marks the first sign of a direction that we will now discuss: the turn towards abstraction.

Figure 5: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1911. Study for a cemetery building surmounted by a cupola. Gold, black ink, white tempera on greenish tracing paper. 46.4 x 26.4 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.112 / Figure 6: Antonio Sant’Elia, Italo Paternoster, 1912. Design for a new cemetery in Monza: Temple of Fame. Perspective view. Gold, black and blue crayon, black and blue ink on paper. 76.5 x 88.6 cm. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.113

From Figuration to Abstraction

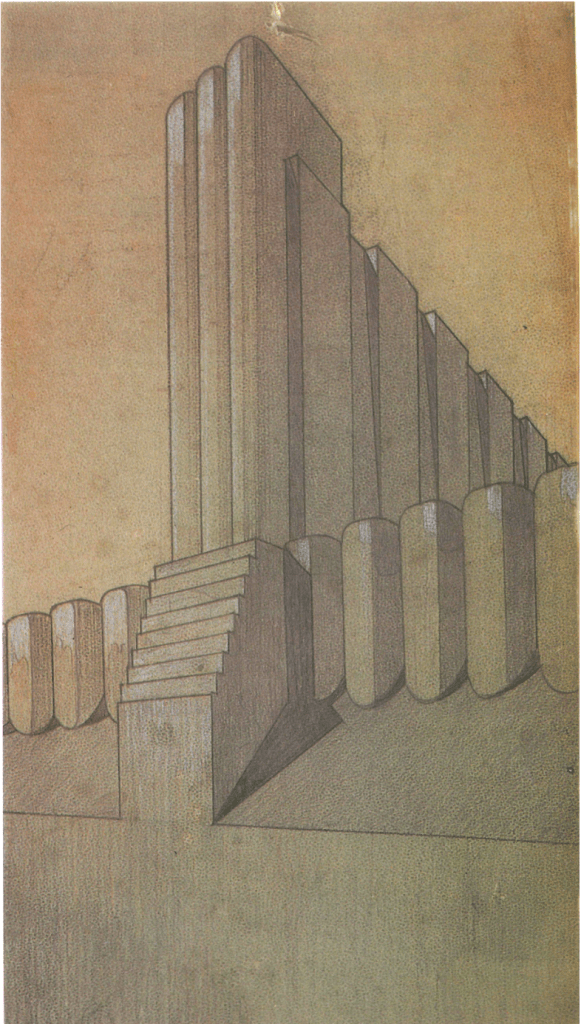

Before we continue to examine how the grotesque evolved into the Città Nuova, there’s a particular period in Sant’Elia’s life that shows a radical change in direction. While he was yet to join the Futurist Movement, the year 1913 marks a turning point in his career that parallelized the path the Futurists were taking. Prior to this year Sant’Elia’s work was still occupied by historicist roots, which can be seen in the many church drawings he made during this period. Although grotesque imagery started to disappear and his search for abstract monumental forms became stronger, his structures still contained historical features; often referring to medieval Lombard churches with heavy masonry. Only a few months later Sant’Elia produced a set of drawings wherein every decorative element and reference to historicism was abolished. The drawings, entitled ‘Dinamismi’, show the first complete break with history as they simply display abstract volumetric masses. Scale, materiality, color and any suggestion of detail are entirely diminished, as for any social, cultural or urban dimensions; resulting in a mere presence of blank monoliths (Figure 7, 8). The Dinamismi should be understood as a “self-gratifying mental abstraction”, revealing Sant’Elia’s continuing search for a ‘pure’ monumentality; a new abstract architectural language that seems to just ‘pop up’ in his work, which is, however, not the case.11 By 1913, the Futurists tried to form “a new psychological syntax of abstract means”, expressed within all forms of art.12 A leading figure who visually and theoretically contributed to this development was the Italian artist Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916). Toward the end of 1910 Boccioni already explored the possibility of evoking feelings and sensations in the spectator through abstract means (lines, planes, colors), rather than subject matter.13 In his Futurist manifesto The Plastic Foundations of Futurist Sculpture and Painting (1913), Boccioni brought this direction to another level by arguing that “we must consider works of art (in sculpture or in painting) as structures of a new inner reality, which the elements of external reality are helping to build up into a system of plastic analogy, which was almost completely unknown for us.”14 He continues by arguing that this ‘new reality’ determines their aim to “destroy four centuries of Italian tradition”.15 His text shows how a new artistic language started to appear wherein external matter is communicated to the inner psych via pure abstract means and therefore replacing figuration. While Bocconi’s approach was solely directed to the visual arts, it shaped a new way of thinking that spread through all creative practices and Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova was subject to this change. As a matter of fact, the ‘utopia’ he created should be seen as the first urban translation of Boccioni’s new reality.

This reality should, however, not be considered a Futurist discovery. The German notion called ‘Einfühlung’, translated as empathy, was developed during the nineteenth- and early twentieth century; literally meaning ‘feeling into’, an act of projecting oneself into another body or environment.16 This is for example seen in the way paintings and stories are observed or read, as the spectator imaginatively tries to enter its non- existing world in order to ‘grasp’ the atmosphere and is therefore projecting oneself onto the object of perception. The Einfühlung gave art and architecture a justification for the decline figuration and therefore of historicism. According to Theodor Lipps (1851-1914), the philosopher who created and theorized the framework of the Einfühlung, human beings project feelings and sensations onto the object of aesthetic contemplation: “Every act of aesthetic pleasure is ultimately based solely and simply on feeling; even that which is given us by, among others, geometrical, architectural, tectonic, and ceramic lines and forms.”17 Boccioni’s viewpoint closely resembles Lipps’s statement, which shows how Futurism is grounded by a philosophical point of view; to break and reconstruct our understanding of man’s perception of the world; it creates a new reality.

Sant’Elia’s Dinamismi series indicates how he started to construct a new architectural language based on the developments seen within his immediate environment. The abstraction of mass and form reveals how he was aware of the direction the Futurists were taking and it comes with no surprise that he would eventually join the movement a few months later in 1914. It is at this moment in his life that the grotesque imagery of his early years starts to undergo a drastic metamorphose. As figuration has been replaced by abstraction, the literal representation of the grotesque has simultaneously transformed into abstract means. The demonic and threatening emotions that Sant’Elia produced through grotesque imagery are now evoked through mass, weight and form itself. It is this change that allows us to introduce the ‘dimension’ that would radiate through the rest of his work and provided him with the monumental power he was looking for; that of the ‘sublime’.

Figure 7 & 8: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1913. Dinamismi: Architectural Elements. Black, red and green canyon on yellow carboard.

Black pencil, blue and orange carboard. 39.5×29.8cm&45.7×26.3cm. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.68 & p.69.

The Sublime and the Metropolis

In 1757, the Irish philosopher Edmund Burke (1729-1797) published a treatise on aesthetics titled A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful. In this work, Burke defines the sublime as a sensory experience or heightened sense of astonishment, where reason is driven out by an irresistible force. As opposed to the classical conception of aesthetic quality as being a ‘pleasurable’ experience, he asserts that ideas of pain and fear are much more powerful than those of pleasure. Burke formulated the definition of the sublime in the following manner: “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogues to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.”18 Burke’s definition closely resembles Ruskin’s valuation of the ‘grotesque’, which we have discussed earlier in this paper; arguing that the spiritual response of fear is ‘higher’ than that of laughter. This parallel shows that the grotesque and the sublime are actually closely related phenomena; allowing us to argue that there’s no hard distinction between Sant’Elia’s early and later work as often suggested. The change from figuration to abstraction is rather a continuation than an alteration; an evolution of the same underlying search for a powerful, painful and frightening experience.

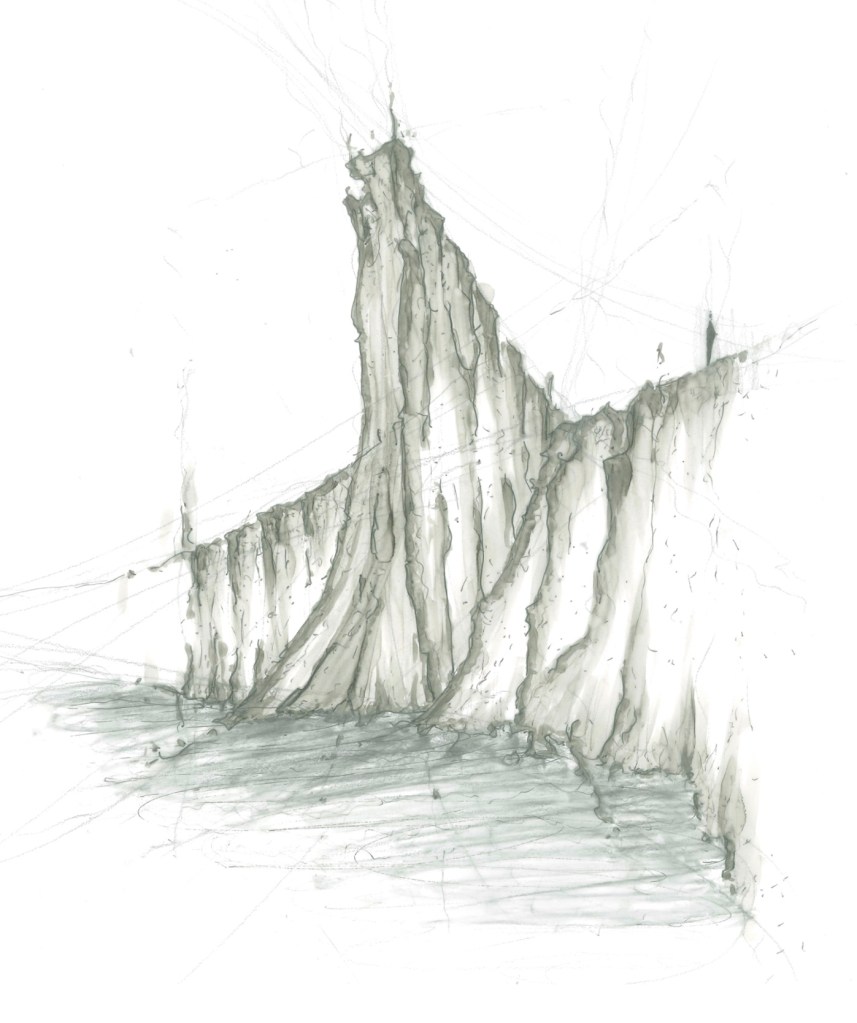

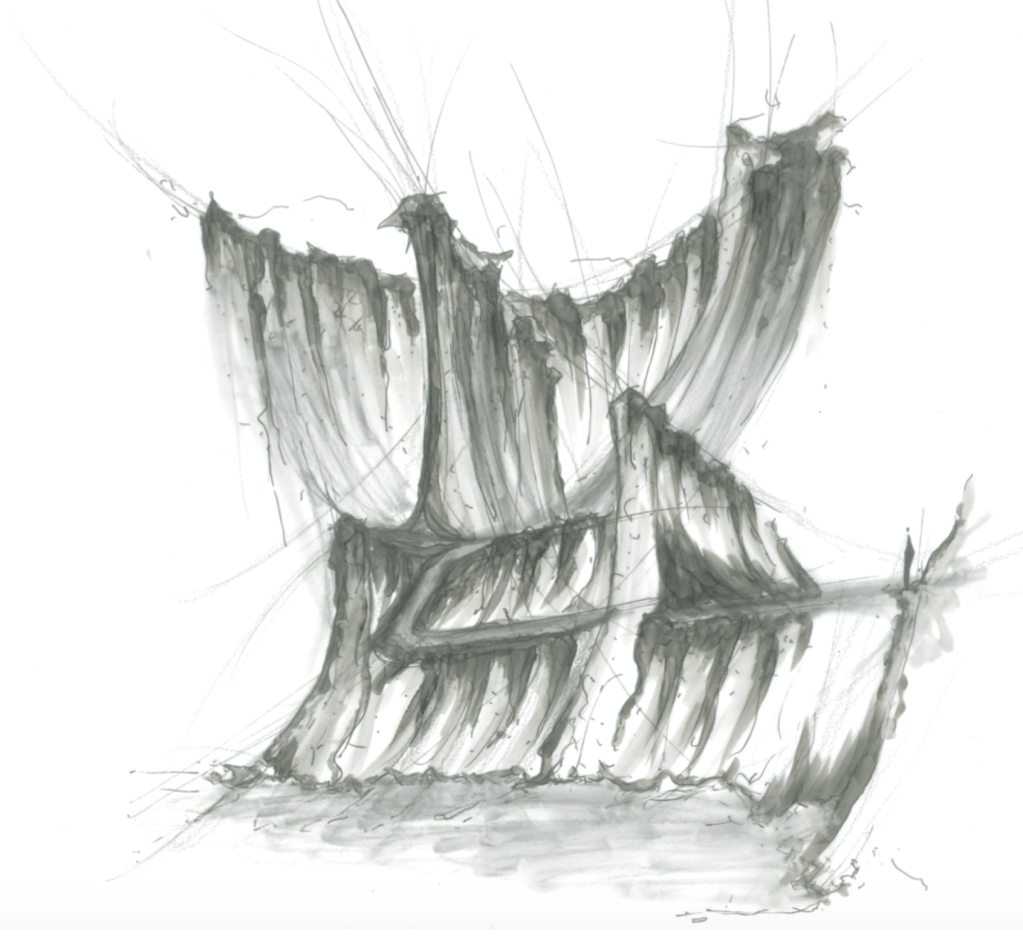

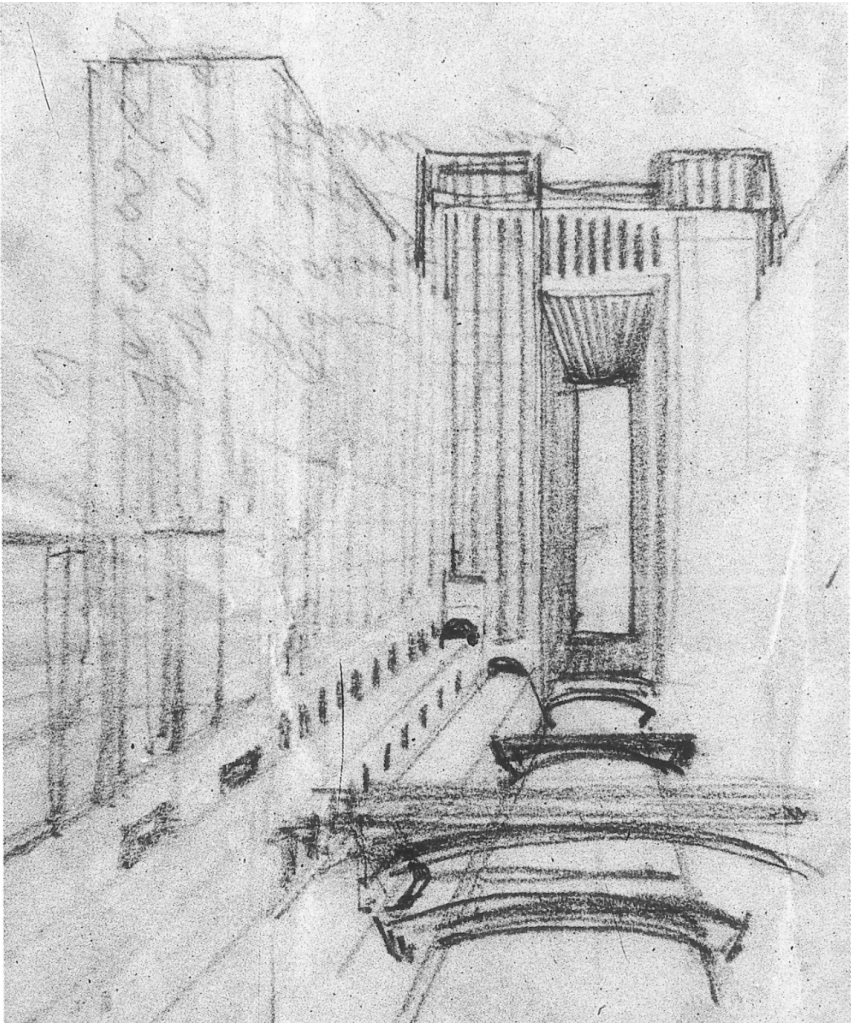

Then, how is the sublime translated into physical form? What generates such an experience? According to Burke, it is through nature that the sublime operates most powerfully: oceans, darkness, obscurity, the vastness of heights and depths.19 Nature’s enormous and ungraspable dimensions are able to evoke a sense of distance within the spectator; a feeling of infinity that is beyond our reach and out of our control. We, as human beings, feel that we are separated from this process. In such overruling environments, our scale seems to disappear into the insignificant. We are made subject to a radiance that is beyond our comprehension; a complete empowerment. In Burke’s age, nothing was able to rival nature’s sublimity. While the Enlightenment gave rise to an architecture of vast scales, endless repetitions and dramatic geometries, such imaginative projects were limited to the drawing board; they could not correspond with reality. It was during the industrialization that a new artifact came to existence: the metropolis. This rapidly growing urban dimension surpassed any other form of urbanity in terms of size; a vastness that eliminated the scale of the individual and prioritized larger masses, crowds and movements. The Viennese architect Otto Wagner (1841-1918) emphasized on this change in the following manner: “The modern eye has also lost the sense for a small, intimate scale; it has become accustomed to less diversified images, to longer and straighter lines, to more expansive surfaces, to larger masses, and for this reason a greater moderation and a plainer silhouetting of such buildings certainly seems advisable.”20 As indicated by Wager, the rise of the metropolis had made a dramatic shift in the way man perceives his environment. The increase of heights, depths and different velocities has resulted in an acceleration of our visual sense. The built environment has therefore lost its emphasis on close range vision and tactility; leading to a world of increasing abstraction. This alteration in perception, where distance is predominant to proximity, has resulted in a situation wherein man is disconnected from his immediate environment; he watches the world go by as a mere spectator. It is this phenomenon which resembles the earlier discussed ‘intangible’ dimension of the sublime, being a power that works beyond our comprehension. In the case of both nature and metropolis, the sublime is provoked by a feeling of terror and awe in the face of an overwhelming greatness. This perceptive alteration is the impetus that has led to the genesis of Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova and his ‘utopia’ should therefore be understood as a response to this drastic transformation. The rise of the metropolis offered him the opportunity to translate his search for the sublime into a present day reality. Figure 9 and 12 picture two perspective drawings of Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova which are then layered onto a drawing that indicates a ‘natural’ scene. This superimposition reveals how we are able to extract nature’s sublimity within Sant’Elia’s design; an artificial representation of nature’s frightening dimensions.

Figure 9: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Study for the Città nuova. Black, green and red ink on paper. 30 x 70 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.86. / Figure 10: Joseph Gardella, 2020. Perspective drawing. Black pencil and grey watercolor on tracing paper. / Figure 11 (Next Page): Figure 9 & 10 in superposition.

The Futurist Machine

The change in perception altered by the metropolis offered architects and urbanists the opportunity to reconstruct the course of the arts in a new metropolitan age. In 1914, shortly after Sant’Elia joined the Futurist Movement, he wrote his highly acclaimed Manifesto of Futurist Architecture.21 In this manifesto, Sant’Elia proclaimed the following statement: “That by the term architecture is meant the endeavor to harmonize the environment with Man with freedom and great audacity, that is to transform the world of things into a direct projection of the world of the spirit.”22 Architecture thus had to reflect the spirit of the times; one that had undergone a drastic metamorphose. He further emphasized on this change in ‘spirit’ in the following manner: “That, just as the ancients drew inspiration for their art from the elements of nature, we – who are materially and spiritually artificial – must find that inspiration in the elements of the utterly new mechanical world we have created, and of which architecture must be the most beautiful expression, the most complete synthesis, the most efficacious integration.”23 This quotation precisely reflects how the Futurists envisioned the new metropolitan human being, namely as an ‘artificial’ entity. We have already reasoned how the metropolis entailed an abstraction of the built environment, as a result of man’s accelerated visual sense. This transformation did, in the eyes of the Futurists, not only result in the abstraction of the world around us but also of ourselves, as human beings. We, the spectators, have become part of this development; a transformation where the being is made void of his figure and reduced to mere fluency. Human beings were, like electrical batteries, seen as “accumulators and generators of movement, with mechanical extensions, noise and speed”; gradually fading away into abstraction.24 It is this direction in Sant’Elia’s oeuvre that marks the final stage of his search for the grotesque, finding its most dramatic and frightening of expressions possible: the inclusion of the human being. While the grotesque figuration of his early years developed into the sublime abstraction of his later years, this final stage does not simply occur in the eyes of the spectator. The human being is now thrown into the great void of metropolitan abstraction; he offers himself, his individual ‘meaningless’ persona, to that which is larger than himself; functioning as a particle within the metropolitan machine.

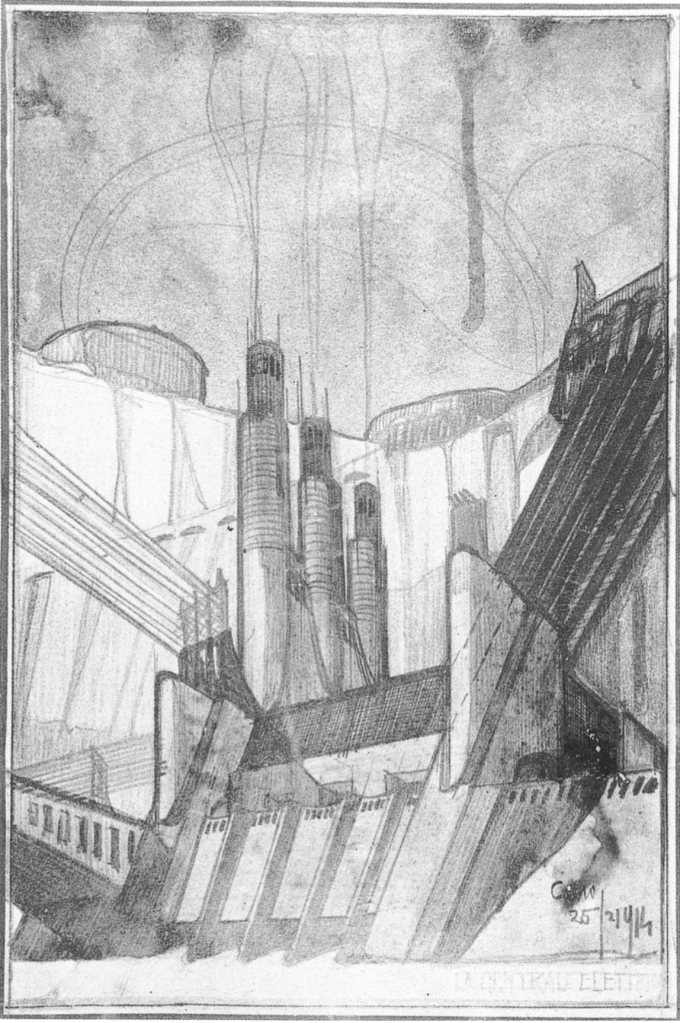

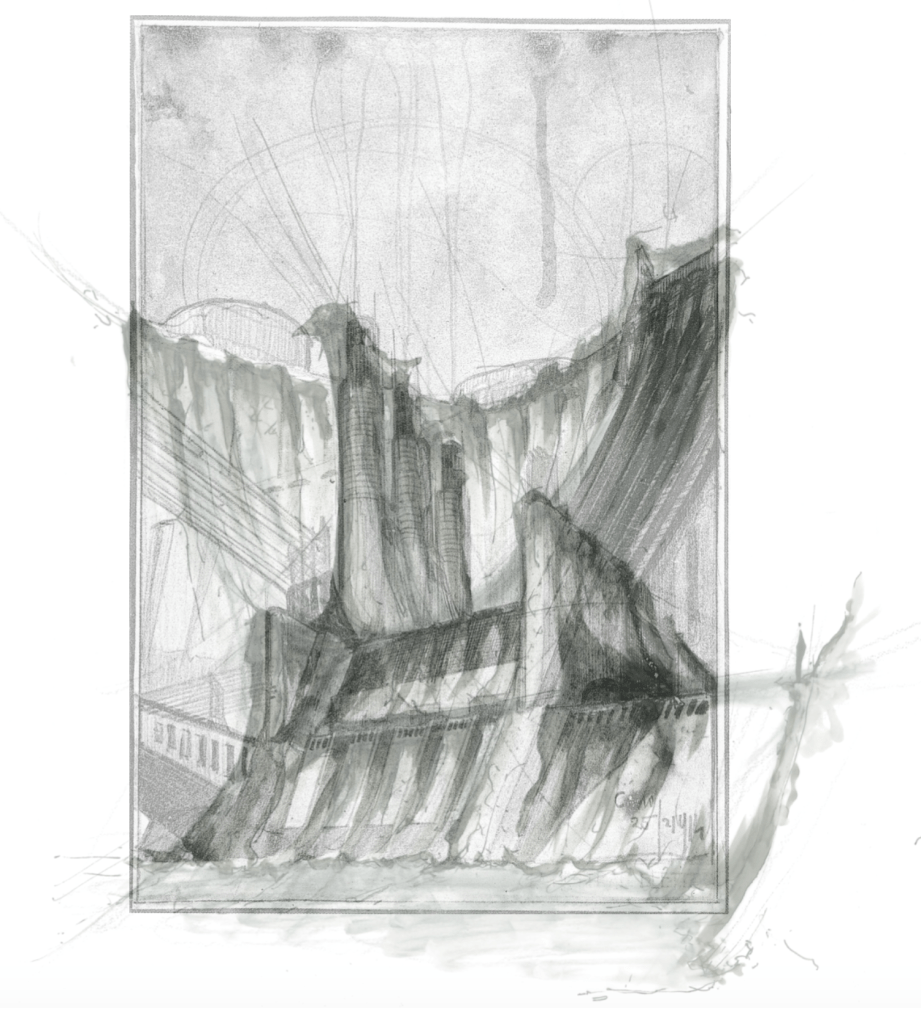

Figure 12: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Power Station. Black, green and red ink, black pencil on paper. 31 x 20.5 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.234 / Figure 13: Joseph Gardella, 2020. Perspective drawing. Black pencil and grey watercolor on tracing paper. / Figure 14 (Next Page): Figure 12 & 13 in superposition.

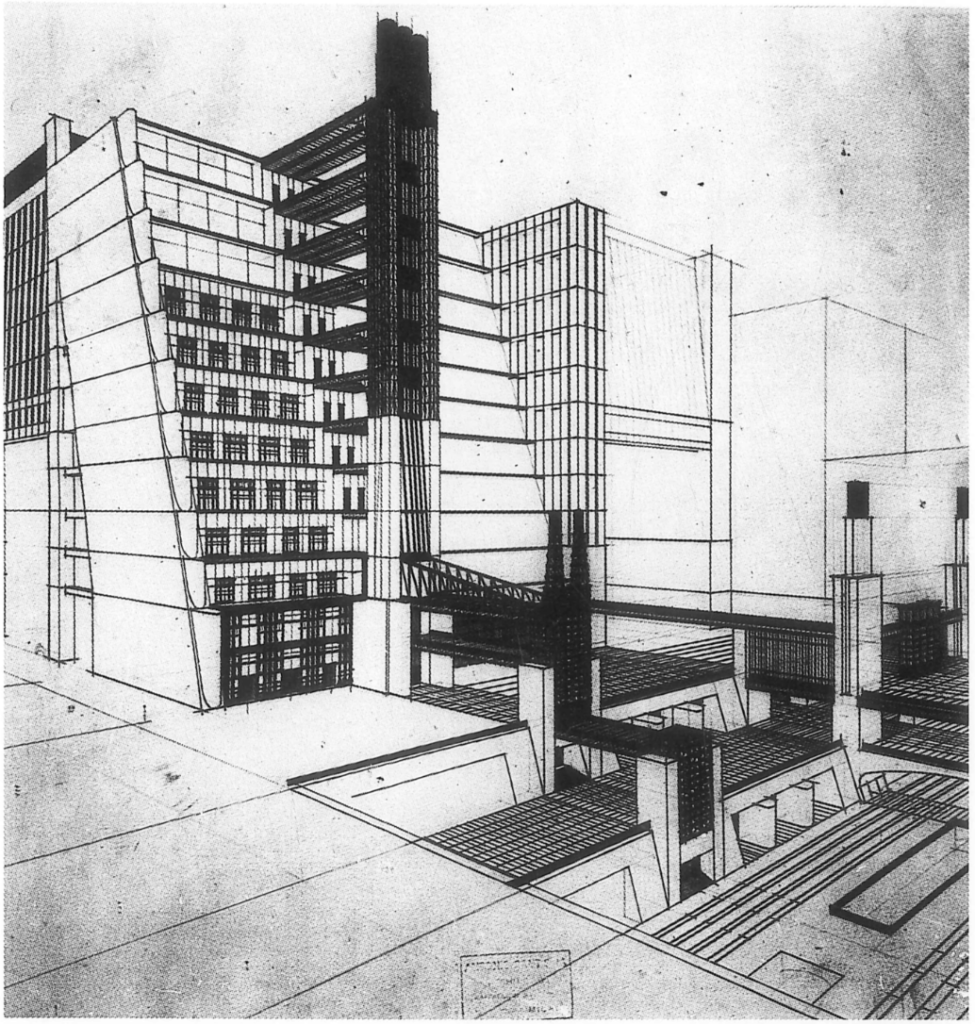

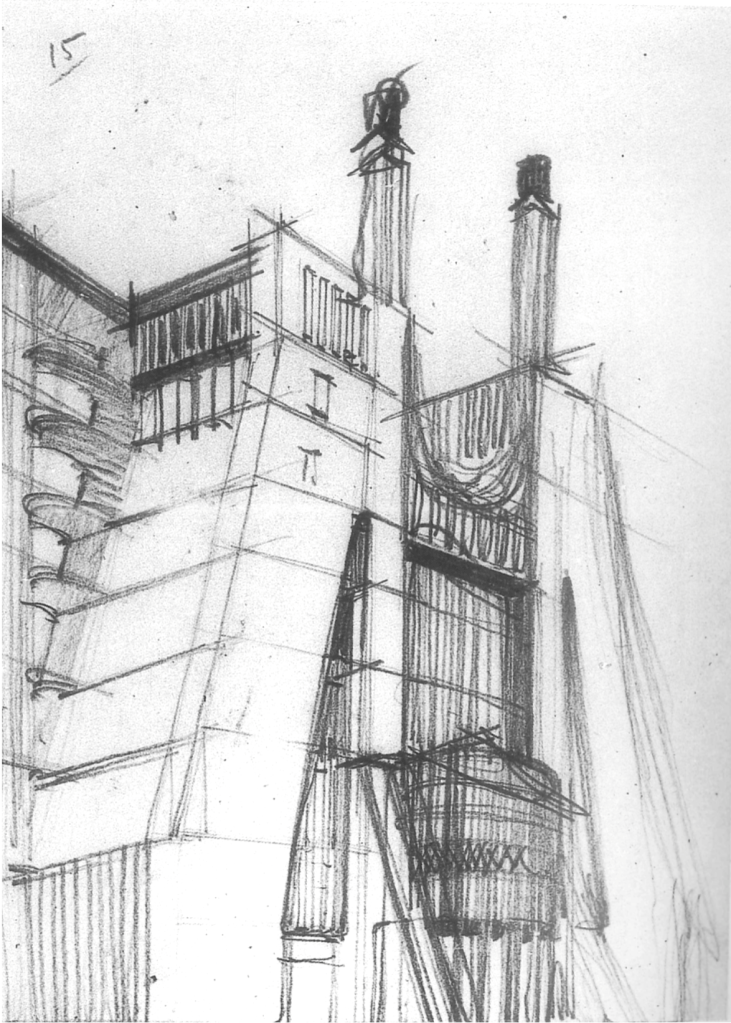

The transformation of becoming estranged from the ‘self’ is a product of an anxiety which is present and cannot be escaped from in an industrial urban milieu, and according to the architectural historian Anthony Vidler (1941-) it has served as a “vehicle for avant-garde architectural experiment”.25 The Futurist Movement was such an experiment and should be understood as an immediate response to this drastic change in perception. Instead of hiding from the unescapable processes of alienation, they aimed to embrace this pain and make it explicit to an almost frightening extreme. In Marinetti’s founding manifesto of 1909, we are able to extract this embracement: “Let’s break out of the horrible shell of wisdom and throw ourselves like pride-ripened fruit into the wide, contorted mouth of the wind! Let’s give ourselves utterly to the Unknown, not in desperation but only to replenish the deep wells of the Absurd!”26 In this quotation, we can sense the determination to completely immerse oneself into the overruling metropolitan forces wherein the modern man exists. Marinetti continues by describing the position of the arts within this new milieu: “Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.”27 Thus, in his eyes, the course of the arts should reflect this conflict; it should embrace and express man’s inner struggle. This, then, leads us to the fundamental theme that radiates through all Futurist manifestos, which is ‘violence’; a trait that reflects man’s courage to seek confrontation with our new reality. Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova (Figure 15, 16) is a physical representation of such an attack; it aims to destroy the past and create a new world of unification and synthetization; turning it into one large metropolitan machine.

Figure 15: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Study for the Città Nuova: apartment building with external elevators, gallery, covered passageways on three street levels. Black ink, black pencil on paper. 52.5 x 51.5 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.270. / Figure 16: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. The Città Nuova: terraced house with elevators from four street levels. Black ink black pencil on paper. 56 x 55 cm. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.269.

The Cathedral of the Future

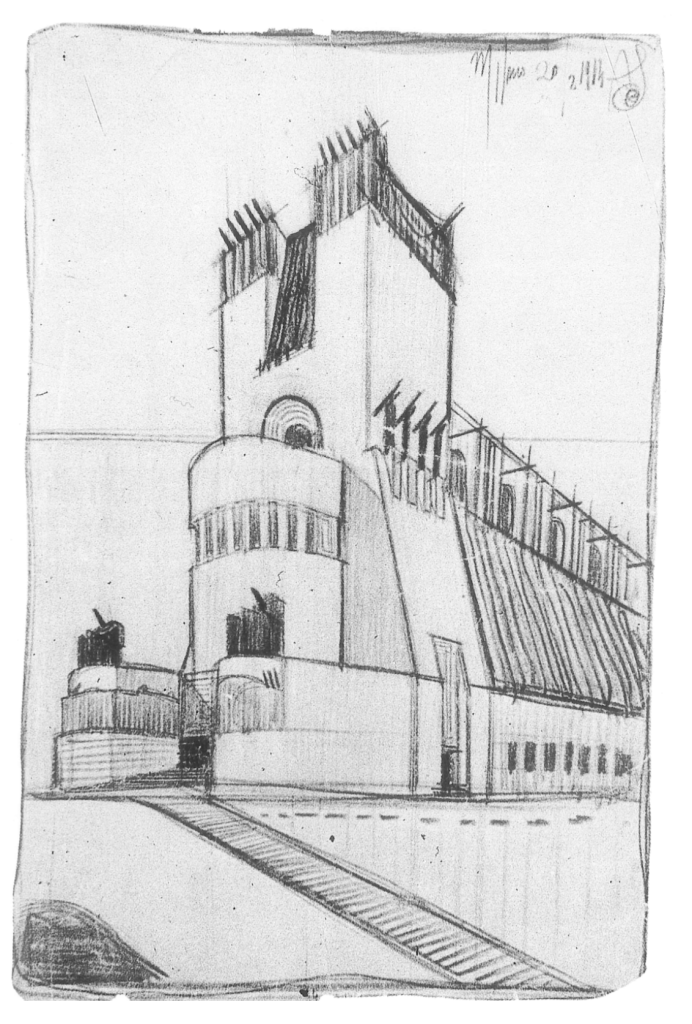

Taking ‘violence’ as the main theme of Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova, we will analyze its features from this point of view, as being attacks on an existing aestheticism. As argued, Futurism is in itself a response against an actuality, and we should therefore read Sant’Elia’s design in such a manner. The first ‘attack’ to be discussed is against historical typologies. In his manifesto, Sant’Elia makes the following statement regarding the matter: “We no longer feel ourselves to be the men of the cathedrals, the palaces and the podiums. We are the men of the great hotels, the railway stations, the immense streets, colossal ports, covered markets, luminous arcades, straight roads and beneficial demolitions.”28 The Città Nuova exemplifies this statement, rejecting all historicist typologies and prioritizing the ones that came to existence during the metropolitan age. Though, there was one particular typology that dominates Sant’Elia’s skyline: the powerplant. Electric power plants started to be constructed at the end of the 19th century and were therefore relatively new. Sant’Elia, who was brought up near Italy’s earliest hydroelectric complexes, envisioned the power plant as the driving force behind his machine city. Up until that moment, power plants were disguised by historical styles; covering up the unpleasant appearance of its machinery. Sant’Elia’s aim was to uncover this decorative mask and fully express its internal logic. This need to “correlate image and function by foregoing the generic aspect of the building” shows how Sant’Elia was ahead of his time; revealing clear modern ideals and even that of high-tech architecture.29 The central position of the power plant in his design clearly shows how he was aware of Tony Garnier’s (1869-1948) ‘Cité Industrielle’ of 1901, being the first comprehensive town planning scheme of the century.30 In both instances, the power plant functions as the central source that makes the city alive and functioning. However, as Garnier’s plan is a complete worked-out mechanism, Sant’Elia’s vision was limited to perspective drawings; providing just glimpses of a possible future. His design also rejected any remaining nostalgia of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement of 1898, which Garnier integrated.31

Sant’Elia’s search for monumentality and the sublime found its shape in the Città Nuova through the design of the power plant. This particular building type seems to replace the church as the sacred nucleus of the new metropolitan age; becoming the cathedral of the future. While the word ‘sacred’ seems to be the wrong connotation given to a power plant as it simply has a secular function, we are still able to trace Sant’Elia’s romantic search for architecture’s spiritual dimension; creating an object of worship. While the Città Nuova seems to completely abandon historicism, as acknowledged in his manifesto, church architecture still radiates through the abstract forms of his power plants. Figure 17 and 18 picture a power plant and a church drawn during this period. Both examples are similar in terms of architectural elements. The elongated mass of the powerplant clearly resembles the nave of a church; containing both buttresses and high clerestory windows. Both examples further have a monumental approach way that leads to a prominent front façade, occupied by a central tower; usual features of Medieval church design. We are therefore able to argue that the powerplant has replaced the church as object of ‘worship’ within a new age. Being the generator of metropolitan forces, it has become the symbol of modern life; a world based on energy.

Figure 17: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Study for a power station. Gold, black pencil on paper. 25.9 x 18.5 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.235. / Figure 18: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Monumental building: Possibly a design for a church in Salsomaggiore. Black, red, blue and orange crayon on paper. 30 x 20 cm. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.215.

Nudity

The internal logic of the metropolitan machine had to be expressed instead of being hidden; a direct projection of the man’s new artificial spirit. The necessity to expose, or in other words to be ‘naked’, was an attack on the way historicist and particularly neo-classical architecture suppressed and disguised man’s modern spirit. Sant’Elia expressed this in the following manner: “The house of concrete, glass and steel, stripped of paintings and sculpture, rich only in the innate beauty of its lines and relief, extraordinarily ‘ugly’ in its mechanical simplicity, higher and wider according to need rather than the specifications of municipal laws.”32 He further adds that “decoration as an element superimposed on architecture is absurd, and that the decorative value of Futurist architecture depends solely on the use and original arrangement of raw or bare or violently colored materials.”33 What immediately strikes us in the first quotation is his association of ‘ugliness’ with mechanical simplicity. The materiality of his design is thus not intended to beautify or provide one with an aesthetically appealing image, but rather to be an honest projection of the machine’s ‘own skin’ by exposing raw textures. This association once again reveals how the Città Nuova continues Sant’Elia’s early search for the grotesque, which has now evolved into a metropolitan context.

Degrees of Movement

The third attack Sant’Elia makes is on the infrastructure of the historical urban tissue. Metropolitan traffic is not limited to the earth’s surface and rejects any form of planarity. In his manifesto, he argues that roofs and underground spaces “must be used”, which would make objects useful from all possible sides, while simultaneously diminishing the importance laid upon façades.34 This, then, leads to an urban fabric wherein there’s no front nor back and therefore rejects the representational ‘mask’ of historicist architecture. As Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova is envisioned as a continuous chain of intermingling and overlapping traffic lanes that “plunge many stories down into the earth”35, his system becomes isotropic in nature; it has “no inside or outside, no center and no periphery”.36 This acknowledgement allows us to suggest the reason why Sant’Elia never drew any plans for the Città Nuova, as it was never intended to be a completed object; it has no beginning nor end, for it is in a constant state of continuation. His perspective drawings should therefore be understood as fragments of a possible city, “linked as episodes of a virtually unitary reality”.37

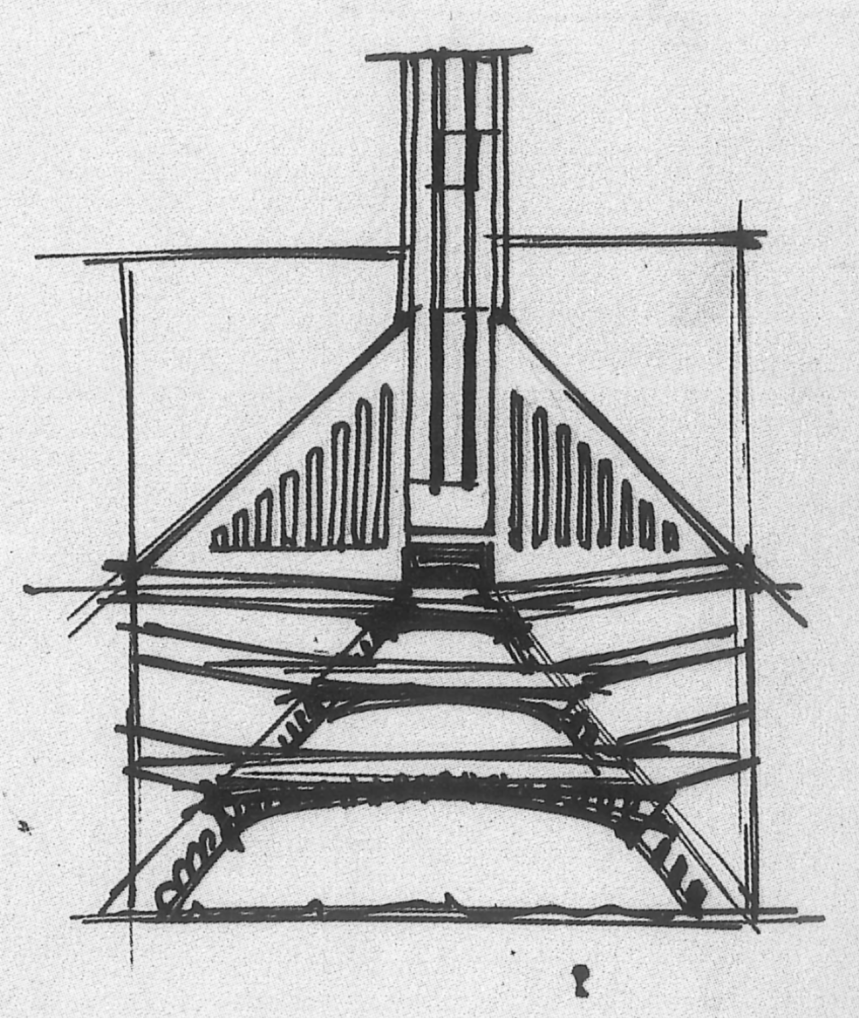

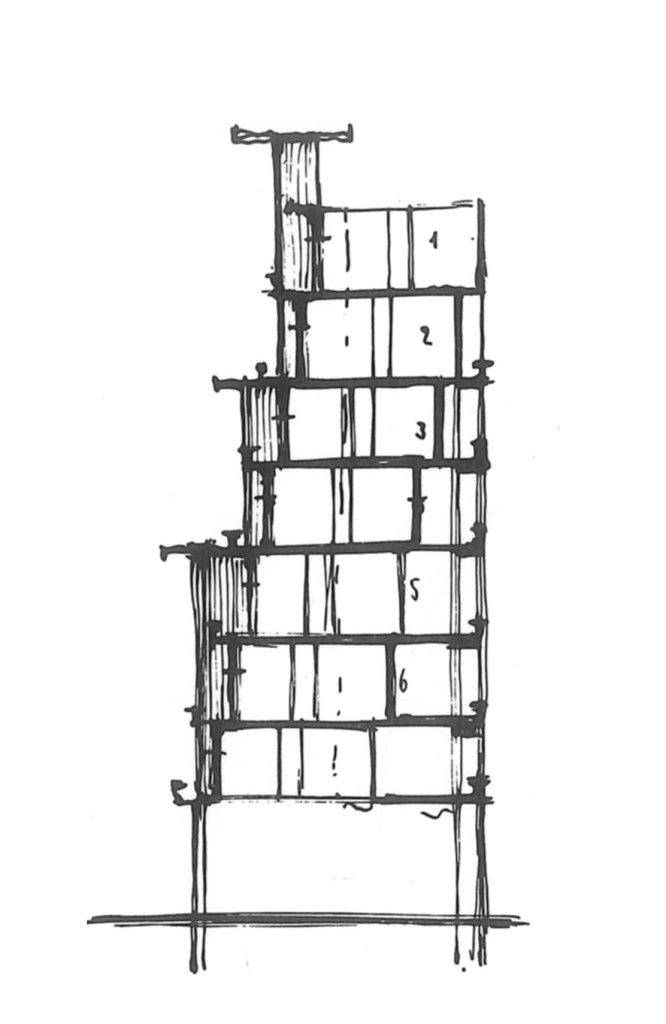

The infrastructure of the Città Nuova is typologically organized according to vehicle and speed. Pedestrian walkways, automobile roads and tramways superimpose each other from top to bottom respectively and are “carefully circumscribed areas”.38 The three traffic lanes are connected via bridges, escalators and elevators, of which the latter transfers pedestrians from their residences downward to each layer of movement. This execution of traffic flow (Figure 19, 20) bears resemblance to perspective drawings made by the American architect Harvey Wiley Corbett (1873-1954). ‘Future New York’, as seen in Figure 21, is based on the same superimposition of traffic lanes: automobiles and tramways are buried in the ground’s surface, while pedestrian walkways exist in the ‘open air’ above. The different traffic lanes taper outwardly and are connected by thin iron bridges, allowing a maximum amount of light to enter the stories underneath.

Figure 19 & 20: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Study for the Città Nuova: Research relating to bridges and passageways suspended over streets and between buildings. Black pencil on paper. 12.9 x 11.3 cm & 19.9 x 14 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.264. / Figure 21: H. Wiley Corbett, 1913. Future New York. From: L’Illustrazione Italiana. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, p.28.

Habitation and Circulation

As earlier discussed, Sant’Elia lived the bigger part of his life in Milan: a city marked by unhealthy living conditions as a result of an extreme building boom. His Città Nuova gives a direct answer to this contemporary issue by creating a new system of high-rise residential complexes wherein each living unit receives a maximum amount of light, view and accessibility. This colossal living mechanism, known as the Casa Nuova, continuously reappears throughout Sant’Elia’s drawings, of which its structure is shaped in accordance to the urban fabric underneath. Habitation and circulation flow into each other in order to optimize movement from private to public domains, and vice-a-versa. As discussed, the different stories of infrastructure stagger upwardly in order to allow light to inhabit each level and isolate different degrees of speed. This process of staggering masses does not stop at the foot of the building, but it continues into the dimensions of the residential complexes above. Each gallery slightly tapers inwardly (Figure 22) and is therefore allowing all individual apartments to receive a maximum amount of light and ventilation. This continuous use of oblique setbacks, which are either made of large steel planes or concrete molds, also reinforces the impression of height and depth; a feature which resembles the overwhelming experience of being in the depth of a valley or on the top of a mountain. Almost all structures found in the Città Nuova are characterized such sloping forms; suggesting the internal transfer of loads and therefore of movement. Instead of a direct confrontation between vertical and horizontal elements, the use of diagonals allows the human eye to gradually follow its direction. As opposed to a usual skyscraper, which is mostly accentuated by height, the Città Nuova thus integrates both height and depth in order to activate a more deepened and dramatic experience in the spectator; once again revealing how the sublime radiates in his design.

The efficiency in movement between public and private space is the result of a displacement of vertical transport systems. High-rise elevator towers, referred to in the manifesto as “serpents of steel and glass”, are placed on the outside of the Casa Nuova and facilitate a direct access to each level.39 Sant’Elia is argued to be the first architect to have come up with this solution: to house elevators in separate units and treat them as “autonomous channels of vertical structure”.40 By creating a direct link between outside space and individual living units, the entire ground floor is opened up in order to allow traffic to flow uninterruptedly. The most common variation of the Casa Nuova consists of two mirroring terraced building blocks which are connected by reinforced concrete parabolic arches abutting one another (Figure 23, 24). The open space underneath functions as an interior street, subsequently edged by rows of shops and offices. Urban traffic therefore continues to flow inside the dimension of architecture, a feature which is clearly inspired by Giuseppe Mengoni’s Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, a covered shopping street located in Milan that opened in 1878.41 Architecture and urbanism, which are usually read as outside and inside territories, are in the Casa Nuova reversed: habitation takes place on the outside while traffic intersects from within. This attribute once again illustrates Sant’Elia’s treatment of architecture and urbanism as a unified system of movement; converting both dimensions into one unified metropolitan machine.

Throughout this paper we have drawn a continuous line from Antonio Sant’Elia’s early work, a rather unknown part of his oeuvre, to the climactic end-phase of his life; represented by this paper’s case study: ‘La Città Nuova’. Both phases, which seem to be completely polarized architectural vocabularies, have in this paper been brought together. By having constructed a bridge between the two, we have been able to understand how Sant’Elia translated a small-scaled architectural expression into an all- embracing urban vision. We have argued how the Città Nuova was actually grounded by the exact same force as found in the symbolic iconography of his early years: the grotesque. This ‘force’, which he first expressed through symbolist imagery and later through the sublime, was understood as being a product of the terrifying dimensions of the modern metropolis. Then, what does this connection tell us about man’s position within his new habitat? As mentioned, Sant’Elia clarified that through the Città Nuova he aimed to ‘project’ the spirit of the modern man in the built environment. The integrity of habitation and circulation, the fearless exposure of the ‘ugly’ machine, and the complete reconfiguration of infrastructure and typologies, were a means of translating his conception of the future spirit in its most ‘truthful’ embodiment. The act of seeking conflict with the inhumane weight of the metropolis, instead of hiding from it, was in his eyes a necessity; something which was only possible if one could break loose from past nostalgia through great courage and violence. Sant’Elia’s Città Nuova is therefore not only a physical translation of a personal melancholia, but it also reveals a contemporary issue regarding man’s position in an estranged and over-dimensioned habitat wherein one’s scale diminishes into the insignificant. His design represents a mentality: one of confrontation, exposure and free-will, as opposed to being subject to a conformity; a victim of an anxiety. Sant’Elia therefore teaches us to build our future by confronting the realities that lay in front of us; to face them with great commitment and transparency.

Figure 22 (center): Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Section of a terraced house. Black ink on paper. 28.5 x 28.8 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.254 / Figure 23 & 24: Antonio Sant’Elia, 1914. Study for a terraced house with external elevators. Black pencil on paper. Unknown measurements & 16.5 x 13 cm. Antonio Sant Elia: The Complete Works, p.258.

Endnotes

1 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 35.

2 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 14.

3 Robert Knopf, Bert Cardullo, Theater of the Avant-garde, 1890-1950: A Critical Anthology (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2002), 189.

4 Robert Knopf, Bert Cardullo, Theater of the Avant-garde, 1890-1950: A Critical Anthology (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2002), 189.

5 Frances Connelly, The Grotesque in Western Art and Culture: The Image at Play (Boadilla del Monte: Antonio Machado, 2015), 41-44, 114, 295-303.

6 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 9.

7 Richard Etlin, Turin 1902: The Search for a Modern Italian Architecture, From: Esposizione d’Arte Decorativa Moderna, Regolamento Generale” (Turin, 1901), In: ER. Fratini, ed., Torino 1902, polemiche in Italia sull’Arte Nuova (Turin: Martano, 1970), 134.

8 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 35.

9 Antonela Corban, Symbolism of the Serpent in Klimt’s Drawings (Dijon: University of Iasi, University of Burgundy, Unknown Date), 194.

10 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 44.

11 Luciano Caramel, Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1988), 21.

12 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 78.

13 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 77.

14 Umberto Boccioni, The Plastic Foundations of Futurist Sculpture and Paining (Florence: Lacerba, 1913), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 88.

15 Umberto Boccioni, The Plastic Foundations of Futurist Sculpture and Paining (Florence: Lacerba, 1913), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 88.

16 Joanna Ganczarek, Thomas Hünefeldt, Marta Olivetti Belardinelli 141, in: “Einfühlung” to empathy: exploring the relationship between aesthetic and interpersonal experience, Cogn Process 19, 141-145 (2018), 141.

17 Renato De Fusco, L’idea di architettura: storia della critica da Viollet-Le-Duc a Persico (Milan: FrancoAngeli, 2003), 43.

18 Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful (London: Printed for R. and J. Dodsley, 1757 ), 58-59.

19 Terrence Des Pres, Terror and the Sublime, in: Human Rights Quarterly, Vol.5, Vol.2 (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983), 137.

20 Charles Bohl, Jean-Françios Lejeune, Sitte, Hegemann and the Metropolis: Modern Civic Art and International Exchanged (New York: Routledge, 2009), 35.

21 The authorship of the ‘Manifesto of Futurist Architecture’ is questionable. It is argued that Filippo Marinetti edited Sant’Elia’s ‘Messagio’ in order to make it applicable to the extreme ideals of Futurism. The vocabulary of the manifesto is not in sync with Sant’Elia’s writing. ‘New City’, being the common caption of his drawings, is now replaced by ‘Futurist City’; a term he would usually refuse to mention. Furthermore, the following claim is made in the manifesto: “After 1700 there was no longer any architecture”. This would indicate a decline of his early work and sources of inspiration. Source(s): The Works of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future, 168. Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works, 43.

22 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 172.

23 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 172.

24 Luciano Caramel, Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1988), 45.

25 Kate Nesbitt, The Sublime and Modern Architecture: Unmasking (An Aesthetic of) Abstraction, in: New Literary History, Vol. 26, Vol. 1, Narratives of Literature, the Arts, and Memory (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 106.

26 Filippo Marinetti, The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (Bologna: Gazzetta dell’Emilia, 1909), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 20.

27 Filippo Marinetti, The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (Bologna: Gazzetta dell’Emilia, 1909), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 21.

28 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 170.

29 Luciano Caramel, Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1988), 23.

30 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 136.

31 Luciano Caramel, Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1988), 23.

32 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 170.

33 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 171.

34 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 171.

35 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 170.

36 Sanford Kwinter, La Citta Nuova: Modernity and Continuity, Zone I/II (1986), 112.

37 Luciano Caramel, Alberto Longatti, Antonio Sant’Elia: The Complete Works (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1988), 35.

38 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 117.

39 Antonio Sant’Elia, Manifesto of Futurist Architecture (Florence: Lacerba, 1914), in: Futurist Manifestos (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1973), 170.

40 Manfredi Nicoletti, L’architettura Liberty in Italia (Bari: Laterza, 1978), 380.

41 Esther da Costa Meyer, The Work of Antonio Sant’Elia: Retreat into the Future (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1995), 112.

Unpublished Work © 2020 Joseph Gardella