Featured image: Photograph, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, 1953. The New Palace and Lawn Seen from the Middle Shoin, Katsura Palace, Japan. 16.5 x 23.7 cm secondary support: 35.6 x 27.9 cm. Gelatin silver print. Collection Centre Canadien d’Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal. / fig. X (above): Pond, Katsura Imperial Villa. Drawing by author.

An essay on the Shōkin-tei chashitsu [teahouse], at the Katsura Imperial Villa, Kyoto, Japan

How does a culture, religion or lifestyle manifest itself in space? When talking about Christianity our mind is immediately filled with images of grandeur: empowering axes, precise symmetries, light radiating though high clerestories, all in search of the absolute. Then, if this is the spatial representation of Christianity and presumably of Western society, what images come to mind when we think and talk about our eastern neighbors, what representation? It is a logical pattern of thought to search for a similar monumentality; a building that is able to rival the grandeur of the cathedral. We might clinch to an image of Hagia Shophia’s spectacular dome and its squinches, or maybe the axis leading to the Taj Mahal – images that satisfy the Western mind. But what about a religion that doesn’t aim for such a direct representation, a culture and lifestyle based on quite a different aestheticism: Zen Buddhism. One could obviously notice a likeable monumentality in the circular-shaped masonry of Buddhist stupa’s or the expressive roof structures of Thais temples. The question is, however, what building reflects the spiritual dimension of Zen most accurately, and how does it manifest itself in space? This paper tells a story about a building type that could form the answer to this question – the typology of the teahouse. We may ask ourselves: could such an introverted and small scaled structure be as rich, spacious and powerful as the great cathedrals of the West? Is this our eastern counterpart?

Thinking in Typologies

This paper is an investigation into the architecture of the Japanese teahouse; a building typology that became known as the ‘chashitsu’ and has since the 16th century retained its position as a “nucleus of Japanese culture”.1 This paper aims to determine the fundamental components of this typology by analyzing a particular case study: the Shōkintei pavilion designed by the Japanese architect Kobori Enshu (1579-1647). This teahouse is located in the stroll gardens of the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto, Japan; a 17th century mansion which became a significant source of inspiration for 20th century Modernists2, and was one of the first places to integrate the ‘teahouse style of architecture’, known as sukiya zukuri, in a broad variety of building typologies. The criteria presented in this paper is physical in its nature; spatial and material dimensions that determine this particular typology. However, as this typology developed out of Buddhist practices, we may assume that the material dimension does not solely construct a truthful image of the Japanese teahouse and that certain immaterial or spiritual qualities should be discussed in order to reach a holistic image of this typology. In other words, to understand the typology of the teahouse one has to include both measurable and immeasurable dimensions that are at stake and we will therefore analyze the teahouse by framing both properties.

The chashitsu is a space wherein one secludes from the outside world and consumes tea. It is therefore logical to assume that this ‘object’ can be read from the inside out; an introverted world completely dismantled from external forces. This is however not the case and we can explain this argument by the help of an analogy. Zen Buddhism teaches to erase the ‘border’ between the self and the world around us; man and nature are one and the same instead of “isolative centers”.3 Space and object are in the same reign not understood as isolative constructions, but as being in a continuous process of change and part of an interconnected whole. In a similar way, the tea ceremony itself doesn’t start when the tea is poured and end when the tea is consumed but is part of a larger continuity. We can therefore argue that this paper is in itself a paradox; the search toward a definition and classification of this typology actually leads one away of thinking in typologies. This thought immediately constructs a follow-up question, namely: “how can a space liberate oneself from dualistic thought, while the space is in itself understood as a distinctive construction?” We shall try to answer this question by ‘reading’ the teahouse as an integral part of a larger context; a chapter within a story, or a phase in meditation.

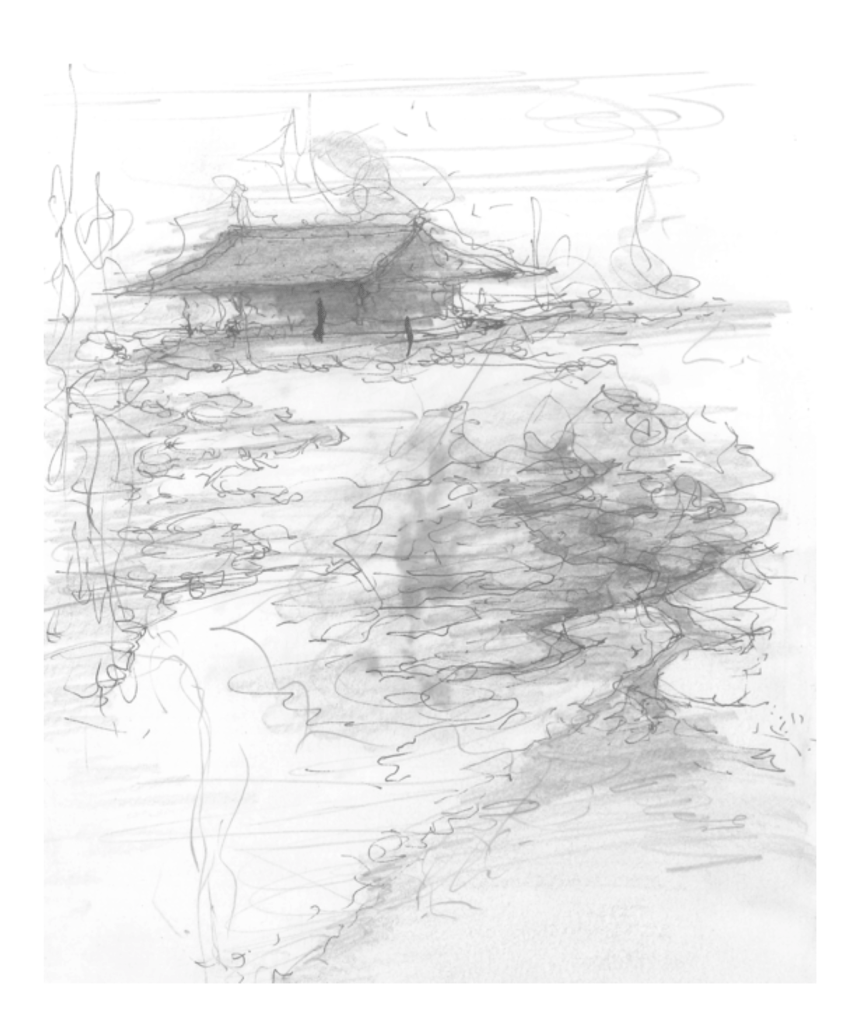

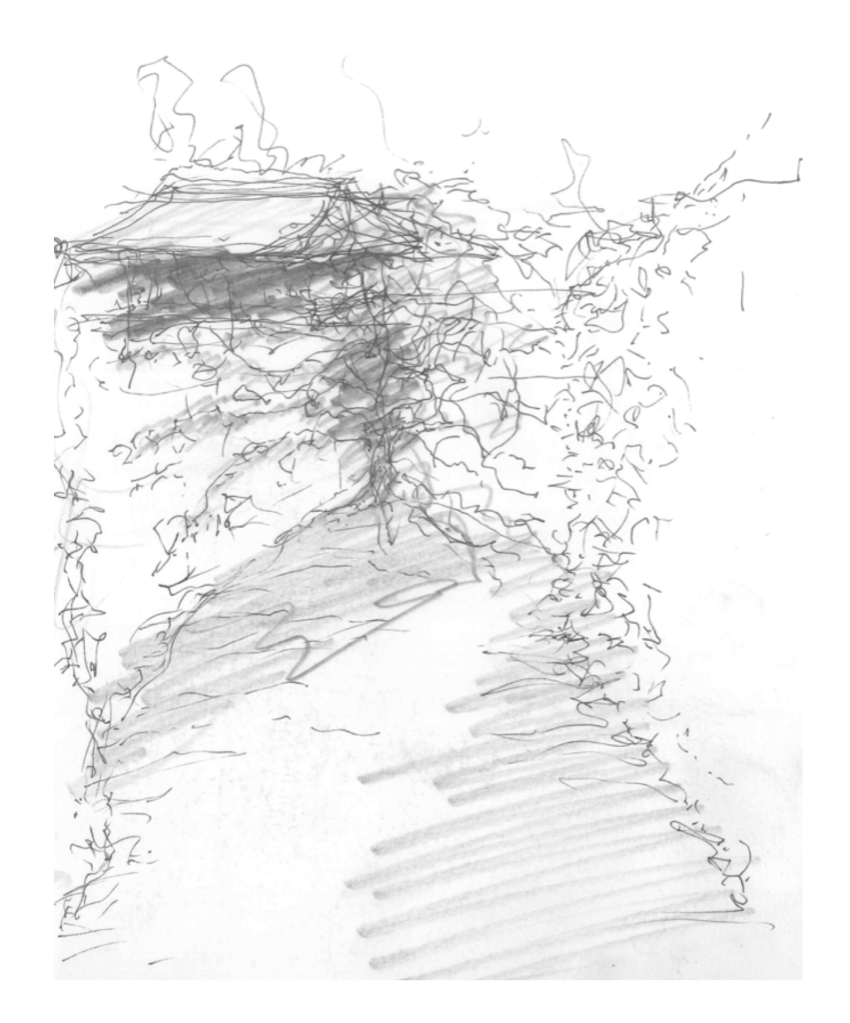

Figure 1: Sketch. ‘The Sumiyoshi Pine’. Katsura Imperial Villa. Drawn by the author. November 2020.

Beyond the Type

The first step of our analysis is to contextualize the process of the tea ceremony without the physical ‘limitations’ of the architectural space. The garden as well as the promenade that leads to the teahouse are known as ‘roji’, literally meaning ‘dewy ground’. We should read the teahouse in relationship to its garden as if it was a ‘heart’ within a spatially layered construction. The roji is ordered in such a way that the pathway sequentially leads toward the teahouse. The Japanese term ‘oku’ is a word that refers to the interior heart of a thing, meaning the “innermost or ultimate space in a sequence of spaces” which is reached without a straightforward path; reflecting the spiritual path taught by Zen Buddhism.4 The roji thus consists of ‘layers’ through which one proceeds. Such a layering of space is usually executed by the use of a traditional Japanese garden technique called ‘miegakure’, literally meaning ‘hidden from sight’.5 This technique is used in order to construct a garden wherein space and object are always partially exposed. If one proceeds along a roji path, only a fragment of a following space or object is revealed to the observer. The intention behind this technique is to “allow the mind the possibility of reconstructing a mental image of the entire edifice” and therefore stimulating one’s imagination to construct that which is unknown.6 By interrupting visual continuities between the observer and the path/objects that lay in front, one is automatically confronted by a limited degree of orientation. The result is a situation wherein the observer has to let go of the need to ‘control’ space and therefore undoing himself of his ego. Such a mental activity is a complete contrast to the hierarchical constructions that define western spaces; instead of controlling nature one becomes an integral part of it. The Baroque garden is for example characterized by such a hierarchical attitude; axes that extend way beyond the garden’s parameters; parterres framed within a distinct geometrical order; all contributing to man’s dominant position over nature. The roji, as a Japanese garden type, does the total opposite; it destructs all possible hierarchies and reflects life as a continuous process of change.

We should understand and read the teagarden and teahouse as a reflection of a culture and religion that is based on the undoing of the ego and therefore constructing a paradigm in which man and nature become one. An example which accurately reflects this mentality is seen in the placement of a particular tree within Katsura’s stroll garden. As one merges his way to the garden’s central pond, one is invited by a sudden vista into this open space. A small cape extends out of the pathway and into the pond, indicating a point of orientation. The end of the cape is, however, occupied by the so called ‘Sumiyoshi Pine’ (figure 1), which withholds one from having a full overview of the central pond and is therefore declining control and orientation. This once again reflects the necessity to undo oneself from his desires and develop a frame of mind which is crucial for participating in the tea ceremony. The teagarden can thus be understood as an essential component that contributes to the realization of a desired frame of mind. This, then, seems to be the eastern counterpart of the forecourts of Christian churches, like the destructed St. Peter’s Basilica, where an in-between space realizes a gradual transition from the chaotic outside world to the sacred interior space of the church. In both cases, the teagarden and the forecourt represent a ‘transition’ and therefore allow one to gradually adapt to the spiritual realm of the architectural space.

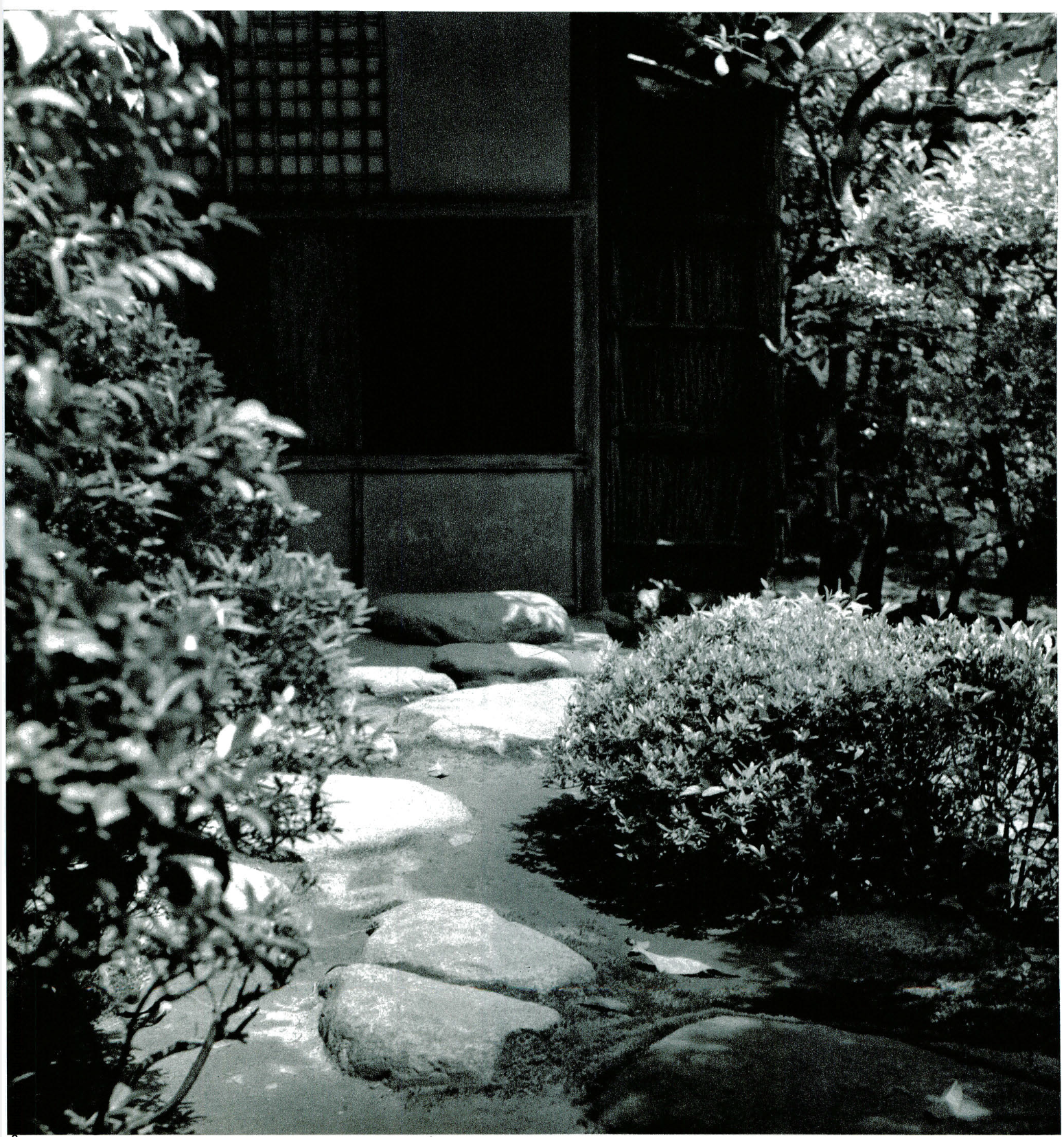

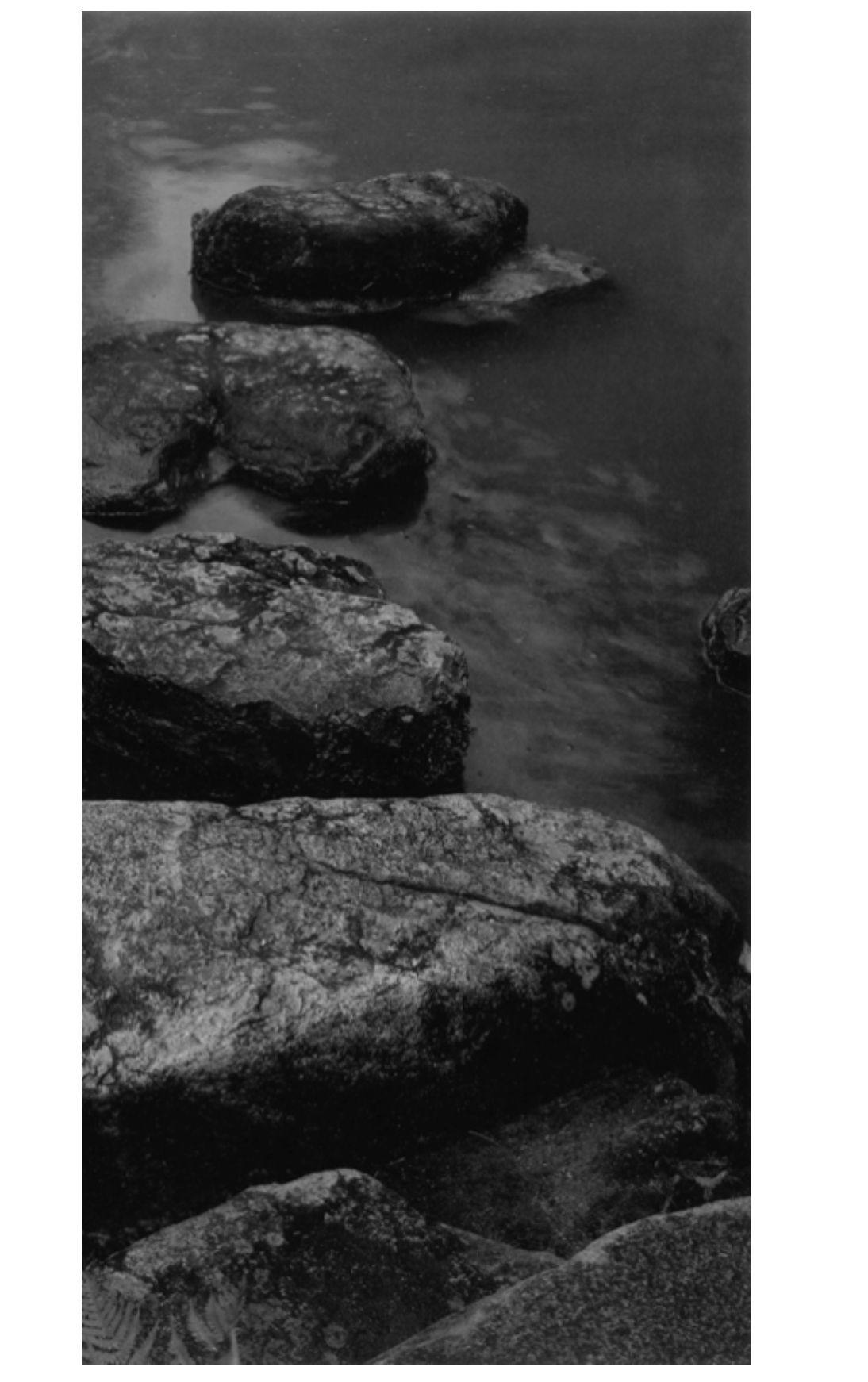

Figures: Path with steppingstones (roji). Steppingstones lead the way through a simple landscaped garden to the teahouse. In: John Kirby, The Sukiya Teahouse, From Castle to Teahouse: Japanese Architecture from the Momoyama Period (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1962). / (2): ‘Tobiishi’ or steppingstones, located near the Shōkintei pavilion. Photographer: Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.158

Symbolism

The Katsura Imperial Villa is a traditional Japanese stroll garden known as a ‘kaiyūshiki teien’ and is therefore not fulfilling the image of a typical ‘roji’. The teahouse is not placed at the heart of the garden, nor is it framed by a clear inner and outer domain; subsequently separated by gates. The stroll garden is a synthesis of several garden types: a roji, a ‘karesansui’ (dry landscape garden) and an ‘ikeniwa’ (pond garden); of which the latter is most prominent in the Katsura Imperial Villa.7 The pond, which is actually an extensions of the Katsura river, forms the nucleus of the garden as the path and several pavilions rotate around it. This type of stroll garden, around which one promenades clockwise, rose to prominence during the Edo period (1603-1868).8 The Katsura Imperial Villa, as one of the first mansions to have executed this new 17th century garden typology, became a symbol of the revival of aristocratic culture in Japan.9 As a matter of fact, it has been argued that it is the most accurate and perfect expression of Japan’s ancient elite culture as it was imagined by early Edo-period elites. It is said that this villa gave rise to an “architectural renaissance”.10

The teahouse is one of many building types that forms an important part of the stroll garden and we could read the entire garden as a ‘story’ constructed of multiple scenes or chapters. By proceeding along the imperial path, one becomes part of this story and every architectural space portrays a particular episode. Therefore, in the case of the Katsura Imperial Villa, such spaces are not solely seen as individual mechanisms, but as constructive parts of a larger paradigm. All pavilions that exist in the garden are formed according to this purpose and it is therefore essential to acknowledge the ‘greater’ scope before we start to direct our analysis to the case study of this paper: the Shōkintei pavilion.

If we read the garden path as it being a metaphor for the continuous process of life, the pavilions become ‘pauses’ within this continuity, like the silences in between the notes. The purpose of architecture is then to offer a ‘distance’ from this process; to watch the world unfold and contemplate on a particular event or scenery. This is the case for the tea-related pavilions within Katsura’s stroll garden; each of them frames a particular garden scene and is therefore externally orientated. This, then, contradicts the image that we have constructed of the teahouse as being a space wherein one secludes from the outside world entirely. The importance laid upon the external orientation of the Katsura teahouses can be shown by explaining the symbolism that is rooted within them. The four structures are ordered around a central pond that correspond to the four cardinal directions, of which each direction is subsequently associated with one of the four seasons (figure 3). The garden zones are thus aesthetically designed according to the season they represent; a model which was already used in the Heian period (794-1185), the last division of classical Japanese history.11 By being designed in accordance to its associated seasons, each teahouse becomes a place where one can observe and contemplate on the particular aesthetic qualities offered by each period in time. The tea ceremony itself is likewise devoted to a particular season and takes place in its associated teahouse. The date of the tea ceremony may also coincide with a natural event such as the “blossoming of the cherry trees” or the “changing colors of the autumn leaves”.12 The season and the mood it generates construct the theme for the ceremony, resulting in a consistency and originality within each ceremony. The names of the four teahouses further have a literal connection with the four seasons. The Gepparō and Shōkatei pavilions, which are associated with spring and autumn and located in the east and west respectively, are placed and orientated in order to frame a particular view. The former literally means ‘moon-wave’ pavilion and frames a view of the autumn moon and its reflection on the water, while the latter is particularly devoted to observing the blossoming during spring and is known as the ‘flower viewing’ pavilion. The Shōiken and Shōkintei pavilions, which are associated with summer and winter and located in the south and north, are named pavilion of ‘laughing thoughts’ and ‘murmuring pines’ respectively. In this case, both names indicate the ‘moods’ associated with the two seasons. The former also contains large sliding doors which can be opened during summer months in order to create a vista into the rice fields located in the south. The latter, which is the case study of this paper, owes its name to an ancient poem meaning the “wind in the pines mingling with the nocturnal song of the koto”.13

We are thus able to conclude that the teahouse functions as an integral part of a larger ‘meditative’ experience and that their participation within this totality is directed to nature’s eternal process. The external orientation is, in the case of Katsura’s teahouses, a constructive part of their design and therefore contrasting the introverted and isolative image associated with the teahouse typology. Before we turn toward the Shōkintei pavilion there’s another crucial form of symbolism hidden in the Katsura Imperial villa and it is necessary to explain this in order to define the contemplative purpose of the four teahouses.

Katsura, the site on which the imperial villa stands, is famed since antiquity for the beauty of the moon rising over the river; it became a place where poets would gather to worship the moon and its reflection on the Katsura river. The etymology of Katsura is also found in an old ancient Chinese legend called ‘the katsura of the moon’. Many poems have been devoted to this legend, wherein the ‘katsura’ is referred to as a tree that is visible at the center of the moon. The moon, as expressed in one of the ancient poems, is understood as a medium through which the poet transcends the autumn landscape: “in the moonlit night, the trees’ colors remain visible in the mind’s eye alone, through contemplating the moon”. In a similar reign it was prince Toshihito (1579-1629), the creator of the imperial villa, who constructed the following poem in 1609:

As I behold tonight

The katsura of the full moon,

Neither morning dew, nor autumn sleet

May know the colour

Of its leaves turned crimson

Hachijō Toshihito, 1609

The prince’s poem shows his awareness of the ancient myth and the site’s relationship to it. It was this form of worshipping the moon that became the driving force behind the realization of the imperial villa. It is said that the site of the imperial villa once contained the moon god’s sacred katsura tree and therefore enabled life on earth. The territory on which the tree once stood became fundamental to construct a relationship with the moon and therefore between heaven and earth, man and the sacred.15 This symbolic meaning once again shows the integrality of the Katsura Imperial Villa and the way in which the typology of the teahouse functions within this totality.

Figure 3: Plan. Katsura Imperial Villa. Cardinal directions and teahouses accentuated. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.142

From Type to Style

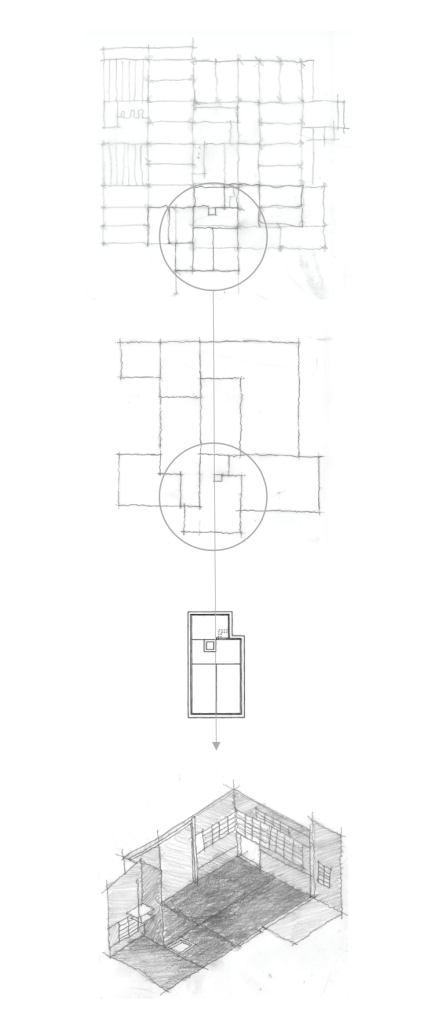

The German Modernist architect Bruno Taut (1880-1938) is credited for ‘discovering’ the Katsura Imperial Villa in 1933 and bringing it to the West.16 Taut’s interpretation and theories spread quickly and Katsura automatically turned into one of the most crucial representative works of traditional Japanese architecture. It became a source of inspiration for Modernist architects as the building’s functionality reflected the ideals of the Modern Movement. This shared fundamental trait, functionality, is in the case of traditional Japanese architecture not merely about realizing mobile interiors for personal sake, but moreover to allow the architecture to adapt to the constantly changing processes of nature; the rhythms of the day. The Shōkintei pavilion can be transformed from one to seven open internal spaces by the use of sliding doors. The inclusion or exclusion of nature can be managed depending on the certain activity that takes place in the pavilion. While the tea ceremony is the prominent function of the Shōkintei pavilion, other functions are included in the design: moon viewing, poetry contests and music appreciation.17 The ‘many-faced’ Shōkintei pavilion is therefore not our ‘typical’ teahouse as it is not solely devoted to the drinking of tea. This, then, allows us to understand the flexibility of Japanese architecture as a method to adapt itself to a particular event and the desired amount of nature’s inclusiveness. The ‘adaptability’ is a result of a modular system which characterizes traditional Japanese architecture. The module, which is used in Japan since the 8th century, is based on the ‘tatami’; which is a rice- straw mat of approximately 1.8 by 0.9 meters used as an integrated floor element. The dimensions of the mat correspond to the height and width of the human being as they were originally used as beds. Over centuries, the mat became a multifunctional platform to host all facets of life and daily practices.18 The use of tatami spread to many building typologies and all social classes and has therefore become a “social and cultural unifier”.19 The dimensions of the tatami are not solely used in plan but also in section, resulting in a three-dimensional unified whole that relates to the proportions of the human body. The essential position the tatami has in Japanese architecture can be reasoned by the fact that spaces are often measured according to the number of mats placed inside. This is also the case for the tearoom, as the particular amount of the mats classifies the room in a certain category. This classification is subsequently decisive for other design interventions that are being made; for example, the ceiling height which has to correspond with the number of mats. According to the 16th century tea-master Takeno Jō-ō (1502-1555) the ideal sized tearoom contains 4,5 tatami mats (four-and-a-half tatami style).20 Rooms of this amount or less were to be defined as ‘koma’ while larger rooms are known as ‘hiroma’. The teahouse typology thus consists of one or several rooms with a particular tatami order. While the ‘use’ of tatami is a constructive part of the typology, the way they are patterned is a stylistic preference of the epoch wherein it was created.

Though, there’s one style which has become so influential for the design of teahouses that it is almost impossible to distinguish typological from stylistic phenomena. This style is known as ‘sukiya zukuri’, of which the word itself originally denoted a building wherein the tea ceremony was executed but eventually became known as the “teahouse style of architecture”.21 The sukiya zukuri style was a response against the aristocratic teahouses of the past that were characterized by grandeur and expensive materials; intending to impress guests with the host’s status. Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), the tea master who is credited for creating it, realigned the tea ceremony as a pure and simple event to be enjoyed by one and all. He argued that the essence of the tea ceremony lays in the appreciation of the “modest and the mundane”.22 The style came to represent four principles that would form the basis for the design of the teahouse: harmony, reverence, purity and silence.23 The Katsura Imperial Villa is one of the earliest examples of aristocratic architecture where the sukiya zukuri style was applied into a great variety of typologies and therefore making the style applicable within the greater scope of architectural design; it was from now on incorporated into a ‘context’ that went beyond the dimensions of the teahouse itself.24 The change might suggest how the Katsura Imperial Villa altered the transition from ‘typological’ to ‘stylistic’ phenomena regarding teahouse architecture. This acknowledgement further strengthens the argument made earlier in this paper by saying that the tea ceremony does not simply start and end in the tearoom but is in the case of Katsura part of a larger continuity; an aesthetic quality applicable to all facets of life.

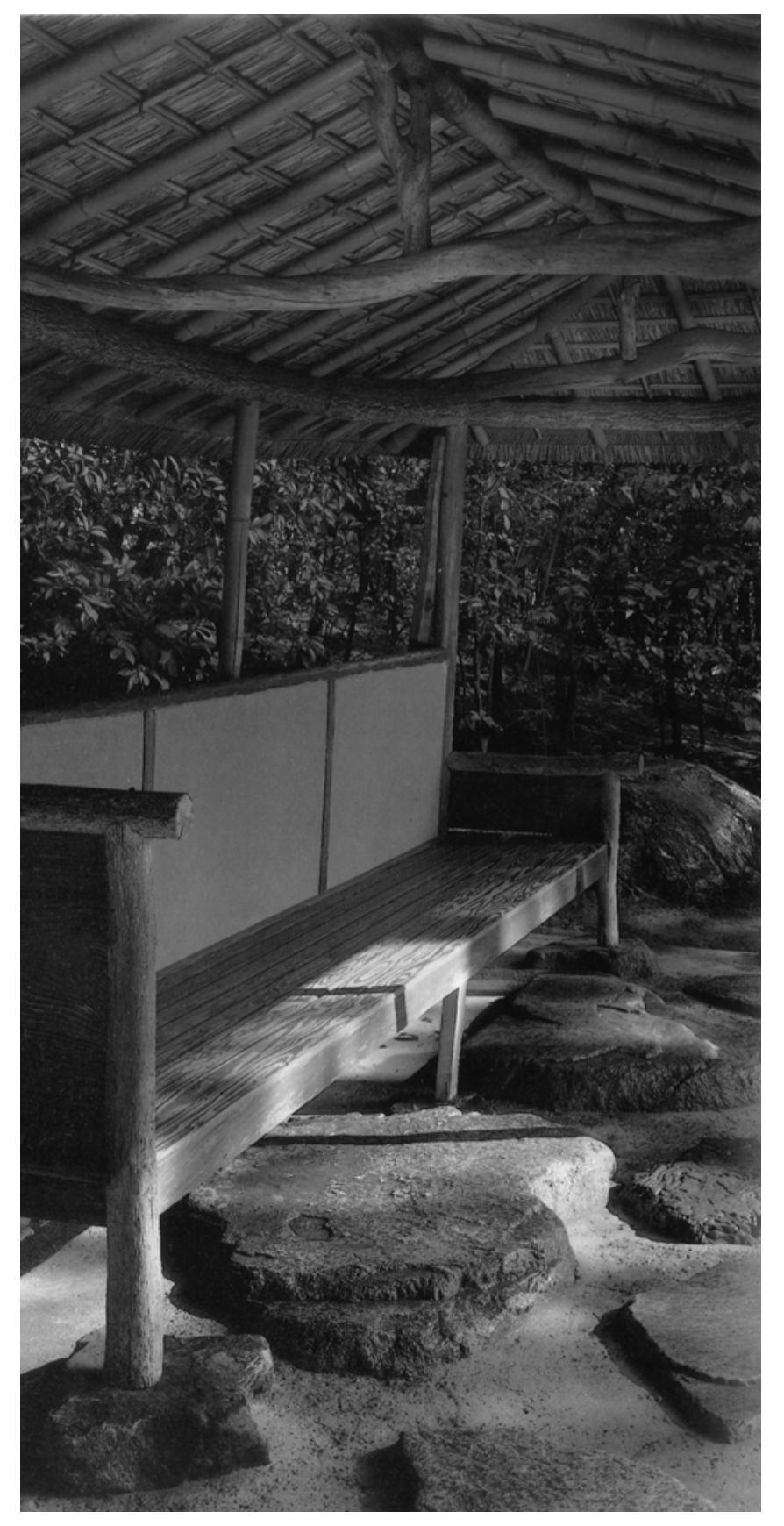

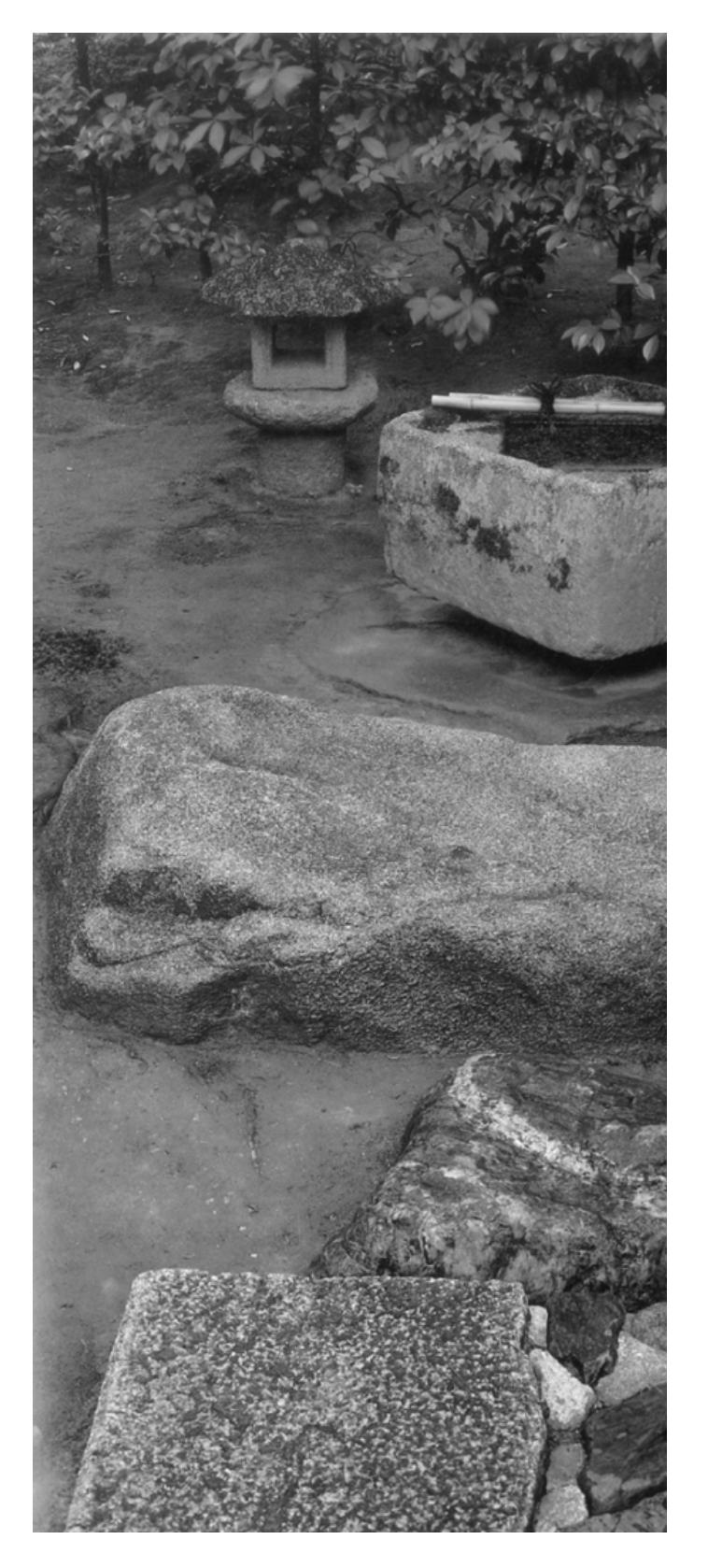

Figure 4: ‘machiai’ or waiting bench, located near the Shōkintei pavilion. Photographer: Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.142 / Figure 5: ‘tsukubaii’ or low water basin and ‘tourou’ or stone lantern, located near the Shōkintei pavilion. Photographer: Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.143 / Figure 6: The northeast side of the ‘Shōkintei pavilion’ approached via the ‘Shirakawa bridge’. Photographer: Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.159

The Garden

The case study of this paper is the Shōkintei pavilion, located in the northeast territory of the Katsura Imperial Villa. As argued in this paper, the tea ceremony is understood as an event constructed of several ‘phases’ that exist beyond the consumption of tea and the teahouse’s physical parameters. We will therefore demarcate our field of analysis to the teahouse and the path leading to its entrance; starting at the waiting booth on the northern side of the Shōkintei. This structure is known as a ‘machiai’, the place where the guests wait to be invited into the teahouse (figure 4). This is a typical feature of the teagarden’s outer garden and is constructed of an open front and a thatched roof, accompanied by a privy.25 The path that leads to the waiting booth is made of steppingstones, which are known as ‘tobiishi’ (figure 2). The arrangement of the stones controls the pace and sets the mood as one proceeds through the garden.26 Another type of stone pavement is known as the ‘nobedan’, wherein different sized stones are made into a plane. This kind of pavement is used at particular stages to allow the guests to control/lower their pace and halt the continuous movement indicated by the steppingstones. In the case of Katsura, as well as the general tea garden, it is applied in front of the waiting booth in order to provide a platform where the host may greet his guests. The starting point of the nobedan plane is marked by a large steppingstone, which is known as a ‘trump’ stone. This stone is used to provide orientation, for the appreciation of a particular view, a crossroad, or in the case of Katsura to indicate the base point of the walk.27 Two other essential elements of the teagarden have been placed next to this stone: a low water basin (tsukubai) and a stone lantern (tourou) (figure 5). The former functions as a basin where the host and his guests can “wash away the impurities of the world”.28 The latter, whom are placed at twenty-four different points in the garden, are meant to be points of reference that indicate directional changes or open up new zones. This ‘change’ is present in Katsura’s garden, as one opens up to a view of the central pond after proceeding along the path. While the space surrounding the waiting-booth is enclosed by greenery, the following ‘scene’ is one of openness and light. This change is a subtle separation between outer and inner garden which in the case of a typical roji would be marked by a middle gate (nakakuguri). The ‘inner’ garden is marked by a meandering path, several lanterns, another waiting booth and an almost five-and-a-half-meter long flat slab of granite, known as the ‘Shirakawa bridge’ (figure 6). Three large steppingstones extend out of the pond and turn it into a natural hand basin, where the guests can clean their hands and mouth before entering the Shōkintei pavilion. It becomes clear that the tea garden functions as a sequential ordering of stages, through which one gradually becomes part of a ‘new’ world. This is the intention behind the tea garden, to leave the ‘chaotic world behind and enter the ‘solitude’ of the rustic tearoom; a process that symbolizes the pure ground in which one is “spiritually reborn” as he passes through it.29

The Tearoom

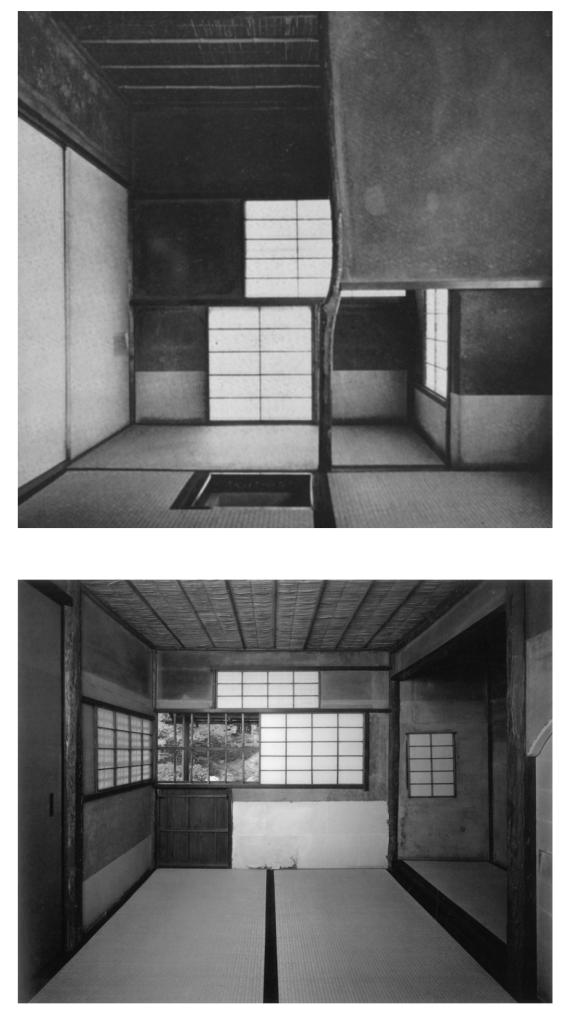

The following case study is the ‘Hasso-no-ma’, or ‘eight window room’, which is the smallest tearoom in the Shōkintei pavilion. The room owes its name to the eight differently proportioned windows which are covered with a translucent paper known as ‘shoji’. This traditional material, which already existed during the 7th century, came into existence in response to the need for a “partition that admitted light” and illuminate a room.30 Shoji screens provide a sense of privacy as one is visually disconnected from the outside world, while it does not reject light, sound and air from entering; thus enhancing natural ventilation. This material is therefore a crucial element within teahouse architecture, as it provides the tea ceremony with a sense of seclusion while it simultaneously strengthens the lightness of the room. The eight windows of the Hasso-no-ma (as seen in figure 7 and 8) are all ordered in order to illuminate a certain place within the room and adapt to a particular phase of the tea ceremony and a time of the day. The adaptability of the shoji screens is an important trait of the tearoom as light should be subdued during the first half of the ceremony and made bright during the latter half.31 The windows on the northeast side (figure 8) are near the guest mats while the lower windows on the southwest side (figure 7) allow diffuse light to fall directly on the host’s mat and the utensils used during the gathering. An interior courtyard, which is adjacent to the southwest wall, enables this part of the tearoom to be lightened. There’s also a skylight above the host’s mat which can be opened during evening ceremonies and is known as the ‘moon-viewing’ window.32 Earlier in this paper we have discussed how the moon is a constantly reappearing motif within the Katsura Imperial Villa and this window once again accentuates its integrity within the design of the teahouse.

Another essential element of the tearoom is the ‘nijiriguchi’, which is the hatch seen in figure eight’s bottom left corner. This small sliding door is the tearoom’s guest entrance, located under a low eave extension on the northeastern side of the teahouse. It has a dimension of only sixty by sixty-five centimeters, placed half a meter off the ground surface. The reasoning behind this dimensioning is that no guest, whatever his rank, can enter the teahouse upright. He must suppress his ego and enter in a “pure, humble frame of mind”.33 This entrance accurately reflects the symbolic attitude of the sukiya zukuri style as a response against the ‘egocentricity’ that characterized earlier flamboyant aristocratic teahouses, while it also indicates a continuation of the ‘mentality’ that has been nurtured throughout the garden.

The layout of the tearoom is known as a ‘sanjo-daime’, meaning a room with three tatami mats and a ‘daime’, which is a three-quarter mat for the host (figure 9).34 The space indicated by the daime is partially separated from the rest of the tearoom by a so called ‘sodekabe’. This is the opaque plane with an open lower section, as seen in figure 7. The plane blocks the guest’s view of a shelf (tana) located at the back side, where the tea is prepared. While guests are not permitted to observe this preparation, the open section allows them to have a visual connection with the host’s movements. The sodekabe plane is edged by an unusually shaped wooden pillar, known as a ‘nakabashira’; an element which was introduced during the momoyama period (1568-1600). This raw tree branch, being the only prominent vertical member inside the room, subtly indicates the importance of informality and rusticity within the tearoom. The foot of the pillar is connected to a square-shaped sunken hearth, known as a ‘ro’. This element is used during winter months in order to heat the tea during the ceremony and is adjacent to the host’s mat. The order of the tatami mats is a direct result of the different entrances to the tearoom: the host’s mat is placed next to the service entrance,

which is subsequently connected to the preparation room; the guest’s mat is directly in front of the crawling entrance, while the mat which includes the hearth is centralized; the fourth mat, known as the nobleman’s mat, is placed in front of an alcove (as seen in figure 8. This alcove is known as the ‘tokonoma’ (which is a space where art is displayed) and represents the highest-ranking component of the room. The position directly in front is usually reserved for the guest of honor as a sign of respect.35 However, by facing the guest from behind (in a usual four-and-a-half tatami room), this orientation is simultaneously a means of showing ‘humility’ as the artworks are not boasted off. The tokonoma is on one side (closest to the center of the room) edged by a wooden pillar known as a ‘tokobashira’. The choice of wood represents the “degree of formality” of the tokonoma and therefore of the tearoom; being either a raw tree trunk or a smooth post. The two items which are displayed in the tokonoma are a calligraphic or picture scroll and a flower arrangement known as ‘chabana’. The latter is the integration of a traditional Japanese artform (ikebana) within a tearoom, of which its aesthetic quality has become representative for the mindset practiced during the tea ceremony. Instead of a blossoming bouquet of flowers, the chabana consists of a deteriorating single flower placed in a rustic bamboo vase; emphasizing a particular melancholic mood. The type of flower and the way it is arranged changes according to the season (‘winter’ in the case of the Shōkintei pavilion) and is therefore responding to the temporary aesthetic mood of the ceremony.36 Like the materiality of the tearoom, the flower expresses a state of ‘decay’ and is therefore revealing its mortality. This inherent quality is fundamental for the tea ceremony and was by Sen no Rikyu referred to as ‘wabi-sabi’; the former being a word which was used to describe sentiments of loneliness and poverty.37 Although it has a very negative connotation, it was understood as a liberation from the material world; resulting in a life wherein one manages to find “peace and harmony in the simplest of lives”.38 The latter is a word which defines a feeling of ‘inconsolable desolation’ associated with one’s sense of mortality and impermanence. Instead of shying away from our mortality, as done in the West39, Japanese seek to embrace the “emotive effect of death” in order to “add force and power to their actions”.40 The combination of both words, wabi-sabi, defines the serene sense of beauty found within the ‘negative’, imperfect, impermanent and incomplete.

Figure 7: ‘Hasso-no-ma’, tearoom in the Shōkintei pavilion. Huessr.tumblr.com: retrieved November 2nd. Photographer unknown. / Figure 8: ‘Hasso-no-ma’, tearoom in the Shōkintei pavilion. Photographer: Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Katsura: Der Kaiserpalast in Kyoto. P.163 / Figure 9: (next page): Plan & Perspective: ‘Shōkintei pavilion’ and ‘Hasso-no-ma’. Drawn by author. November 2020.

Continuity

At the start of this paper we have acknowledged a distinction between measurable and immeasurable components that construct the typology of the teahouse. This paper has ordered the former into an image that represents the physique of the teahouse. The latter, on the other hand, could not be pinned down into such a structure. Though, we have thoroughly tried to ‘grasp’ this immeasurable quality by rejecting to see the typology as an isolative mechanism; but rather as a constructive part of a larger ‘meditative’ continuity. The aestheticism of wabi-sabi and its integration into the sukiya zukuri style, as developed by Sen no Rikyu, show how teahouse architecture grew into a physical expression of an attitude towards life; that of Zen Buddhism. The utmost attention to the simplest daily exercises has altered the mundane to a spiritual dimension independent of one’s wealth or status and to be enjoyed by all human beings. While the West is crowned with great cathedrals that elevate toward that which is set apart from the mundane, this small and introverted teahouse polarizes our image; it retreats itself away from the direct and the absolute, into the daily life of simple gestures.

Endnotes

1 Iris Mach, Chashitsu: The Japanese Teahouse: An Aesthetic System (Vienna: TU Wien, 2012), 1.

2 Marja Savirmäki, Japanese module interpreted: De-quotations of Re-quotations on Katsura Villa (Queensland: Bond University, 2017), 619.

3 Alan Watts, Lecture: The Tao of Philosophy: Myth of Myself, ed. Mark Watts, edited transcripts, (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1955 ed. 1999).

4 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 21.

5 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 21.

6 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 21.

7 Ono Kenkichi, Walter Edwards, Japanese Garden Dictionary: A Glossary for Japanese Gardens and Their History. 2010. Retrieved: October 2020.

8 Sophie Walker, Japanese Garden: The Way, the Body and the Mind (New York: Phaidon Press Limited, 2017), 6.

9 Kunihei Wada, Katsura Imperial Villa (Osaka: Hoikusha Publishing Co., 1962), 102.

10 Nicolas Fiévé, The Genius Loci of Katsura: Literary Landscapes in Early Modern Japan, Volume 37, Studies in The History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 134.

11 Nicolas Fiévé, The Genius Loci of Katsura: Literary Landscapes in Early Modern Japan, Volume 37, Studies in The History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 137.

12 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 39.

13 Nicolas Fiévé, The Genius Loci of Katsura: Literary Landscapes in Early Modern Japan, Volume 37, Studies in The History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 143.

14 Nicolas Fiévé, The Genius Loci of Katsura: Literary Landscapes in Early Modern Japan, Volume 37, Studies in The History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 143.

15 Nicolas Fiévé, The Genius Loci of Katsura: Literary Landscapes in Early Modern Japan, Volume 37, Studies in The History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes (New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2016), 153.

16 Dana Buntrock, Katsura Imperial Villa, Cross Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (Berkeley: University of California, 2012), 2.

17 Naomi Okawa, Edo Architecture: Katsura and Nikko (Tokyo, New York: Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 1975), 100

18 Carola Hein, Lecture: Tatami mat: Floor Cover, Building Block and Lifesyle (Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2016)

19 Carola Hein, Lecture: Tatami mat: Floor Cover, Building Block and Lifesyle (Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2016)

20 Shigernori Chikamatsu, Stories from a Tearoom Window: Lore and Legends of the Japanese Tea Ceremony (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 9.

21 Naomi Okawa, Edo Architecture: Katsura and Nikko (Tokyo, New York: Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 1975), 100

22 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 41.

23 John Kirby, The Sukiya Teahouse, From Castle to Teahouse: Japanese Architecture from the Momoyama Period (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1962), 33.

24 Naomi Okawa, Edo Architecture: Katsura and Nikko (Tokyo, New York: Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 1975), 111.

25 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 11.

26 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 24.

27 Kunihei Wada, Katsura Imperial Villa (Osaka: Hoikusha Publishing Co., 1962), 55.

28 Sen, 1991 3-4, 17 Roji, sequential movement.

29 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 14.

30 Kyung Lee, Shoji and Related Architectural Elements: Their Structure, Applications, and Adaptations. Journal of Interior Design Education and Research (Morgantown: West Virginia University, 1988), 27.

31 Beata Zygarlowska, Climatic Determinism in daylighting strategies of the traditional Japanese room (Cambridge: University of Cambridge, 2004), 13.

32 Kunihei Wada, Katsura Imperial Villa (Osaka: Hoikusha Publishing Co., 1962), 72.

33 Despina Sfakiotaki, Analysis of Movement in Sequential Space: Perceiving the traditional Japanese tea and stroll garden (Oulu: Oulu University Press, 2005), 19.

34 Naomi Okawa, Edo Architecture: Katsura and Nikko (Tokyo, New York: Weatherhill/Heibonsha, 1975), 100. 35 John Kirby, The Sukiya Teahouse, From Castle to Teahouse: Japanese Architecture from the Momoyama Period (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1962), 127.

36 Heinrich Engel, The Japanese House: A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 1964), 289.

37 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 48. 38 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 49. 39 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 49. 40 Andrew Juniper, Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2011), 49.

Unpublished Work © 2020 Joseph Gardella